13 discoveries in the last year have fundamentally altered our understanding of human history

As anthropologists discovered new fossils and artifacts in 2020, our understanding of human history has changed.

Thirteen discoveries in particular offered new and sometimes perplexing insights into where we came from and who our ancestors were.

This year, researchers found the earliest known example of mating between different human populations, as well as evidence that the first Americans arrived from Asia by boat.

Even amid the pandemic, anthropologists and archaeologists around the world have continued to make mind-boggling discoveries about our human ancestors this year.

One analysis revealed that the earliest known example of interbreeding between different human populations was 700,000 years ago - more than 600,000 years before modern humans interbred with Neanderthals. Findings from a Mexican cave, meanwhile, offered evidence that the earliest humans came to the Americas via boat, not land bridge. And researchers also found new reason to believe climate change was responsible for the extinction of many of our ancestors.

Taken together, these discoveries and others bolster and complicate our understanding of human history - the story of who our ancestors were, where they came from, and how they lived.

Here are some of the most eye-raising anthropological findings of 2020.

Scientists already knew that our evolutionary history was full of sex between different human species. But a genetic analysis revealed the earliest known example of mating between different human populations.

Anthropologists already knew that modern humans mated with Neanderthals and Denisovans — two cousins of Homo sapiens — 40,000 to 60,000 years ago.

But a February study showed that the ancestors of those Neanderthals and Denisovans once interbred with a mysterious population of ancient humans in Eurasia 700,000 years ago.

"This continues the story that we've been seeing in studies throughout the past decade: There's lots more interbreeding between lots of human populations than we were aware of ever before," Alan Rogers, an anthropologist at the University of Utah and the lead author of the study, previously told Business Insider. "This discovery has pushed the time depth of those interbreedings much further back."

Our interbreeding with Neanderthals may explain why humans have a low tolerance for pain.

Certain Neanderthal genes, researchers found, code for proteins that convey a heightened sense of pain to the spinal cord and brain. A July study showed that a sample of people from the UK who had inherited those Neanderthal genes experienced more pain than study participants who didn't have them.

Neanderthals also used their hands differently than we did - they were better suited to a squeezing a spear than delicately grasping something between the thumb and forefinger.

Neanderthal hands were bigger than ours, and their thumbs stuck out at a wider angle from their palms than ours do.

According to a November study, this meant that precision grips like the ones we use when writing would have been challenging for Neanderthals.

But these ancestors had powerful squeeze grips — the kind one might need to swing a hammer.

Denisovans are an early human species related to Neanderthals. Until this year, only a meager handful of Denisovan bones had ever been found, all in a single cave in Siberia.

But in February, researchers returned to a cave in Tibet where anthropologists had previously discovered a mysterious 160,000-year-old jawbone. They hypothesized last year that the bone belonged to a Denisovan, but had no genetic proof.

This time, however, they were able to collect ancient DNA from sediment in the cave. That led them to determine that the jawbone indeed came from a Denisovan who once thrived in the cave's harsh high-altitude environment.

Kira Westaway, an anthropologist from Macquarie University in Australia, told Business Insider that the discovery put "a lot more meat on the bones of the Denisovan story — the nature and length of their occupation, their ability to adapt to high-altitude locations, and their behavior and survival capabilities in the hostile environments of the Tibetan plateau."

But not all our ancestors were so hardy. Some went extinct due to to changing climates, new research suggests.

According to research released in November, plummeting temperatures and changing rainfall may have been the "primary factor" behind the extinction of three human ancestor species: Neanderthals, Homo erectus, and Homo heidelbergensis.

By examining more than 2,750 archaeological records, a team from Italy found that the climate cooled by up to 9 degrees Fahrenheit (5 degrees Celsius) on average per year ahead of the species' disappearances.

As the climate changed and their preferred food sources suffered in the cold, both species of Homo lost half of their ecological niche in Africa, Asia, and Europe. Neanderthals, meanwhile, lost 25%, according to the study.

"Even the brain powerhouse in the animal kingdom cannot survive climate change when it gets too extreme," study author Pasquale Raia, a paleontologist from the University of Naples, told ScienceAlert.

The earliest humans to cross from Asia to the Americas proved creative and skillful. They crossed the sea between present-day Siberia and Alaska by boat during the last Ice Age.

Archaeologists determined that stone tools and artifacts discovered in a remote cave in Zacatecas, Mexico, were about 32,000 years old. They described the finding in a July study.

The new evidence upended the idea that the first people arrived in North America after continent-hopping from modern-day Siberia via the Bering land bridge between 18,000 and 13,000 years ago.

During the last Ice Age 32,000 years ago, that land bridge was impassable. So the research suggests the first Americans arrived by sea. According to the study authors, these migrants were likely anatomically modern humans.

Another study of the earliest Americans showed that females played a role hunting big game.

Scientists discovered a 9,000-year-old burial site containing weapons and animal-skinning tools high in the Andes mountains of Peru. They assumed the human bones there came from a skilled male hunter.

But a closer look revealed that this hunter was female. Further analysis of 27 other burial sites across North and South America, which also contained hunting tools and date back to the same time period, revealed that 40% of the hunters were female.

"Female participation in early big-game hunting was likely nontrivial," the study authors concluded.

The finding "overturns the long-held 'man-the-hunter' hypothesis," Randy Haas, lead author of the study and an anthropologist at the University of California, Davis, said in a press release. This outdated archaeological theory suggested men were the primary hunters, while women gathered.

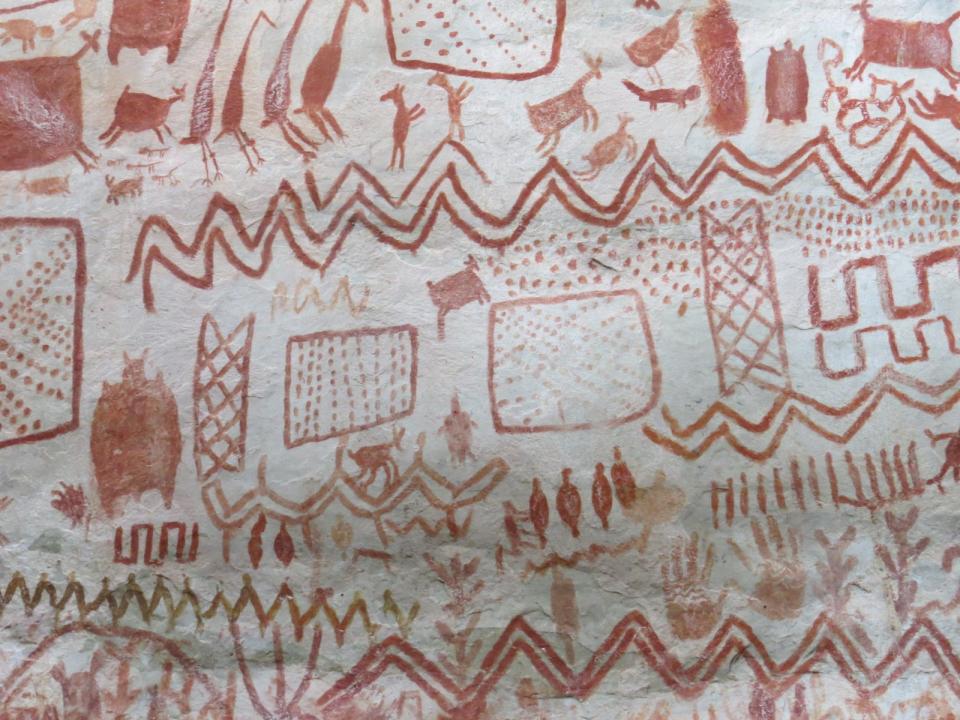

Thousands of drawings hidden deep in the Amazon rainforest tell the story of an ancient tribe's hunting practices about 12,000 years ago.

The drawings, which cover more than 2.5 miles of rock in Colombia, depict scenes of humans hunting mastodons. They also contain images of other extinct animals like giant sloths, ancient llamas, and Ice Age horses.

Archaeologists announced the drawings' discovery in late November.

Other recently discovered rock art in the Americas likely shows a psychoactive plant called datura.

A red pinwheel-shaped drawing found on the ceiling of a California cave may have been part of a hallucinogenic ritual nearly 500 years ago.

In addition to the drawing, researchers found chewed wads of datura stuffed into cracks in the ceiling of the cave. Their analysis also showed that people occupied the cave from about 1530 to 1890 and likely chewed the datura during that period.

According to a November study, the drawing could be evidence that paintings in caves have served as visual aids for drug-induced hallucinations.

On the other side of the world, Egyptologists have unearthed batch after batch of sarcophagi in an ancient city of the dead beneath Saqqara.

More than 160 mummies have been found so far. They'd been buried for 2,500 years — until the first cache of 13 was found at the bottom of a 36-foot-deep shaft in September. Researchers have also found various artifacts in the tombs they've excavated, as well as a trove of animal mummies.

Further discoveries from the site are expected in the coming months.

In England, archaeologists revealed that they'd determined the origin of some of the boulders that make up Stonehenge.

Stonehenge, which is estimated to be about 5,000 years old, is made up of two distinct types of stone slabs set in half circles.

Researchers traced one type, the smaller bluestones, to a site in Wales 150 miles away. Research from July suggests the 30-foot (9-meter) sandstone boulders, called sarsens, that constitute the rest of the monument came from a nearby woodland area.

Still, Stonehenge's builders had to drag the 50,000-pound (22,700-kilogram) sarsens about 15 miles —"which is insane really if you think about it," archaeologist David Nash, the lead author of the study, previously told Business Insider.

Near Rome, archaeologists discovered an ancient city buried underground without ever digging it up. They mapped it using radar.

Using radar to scans below the soil, a group of Belgian and British researchers mapped the entire ancient city of Falerii Novi, which was built around 241 BC and sits about 30 miles outside of Rome. They were able to identify new structures like an elaborate bath house and a large public monument.

The city's last human inhabitants left during the early medieval period in about 700 CE.

Not all ancient archaeological sites are on land. A team in Australia discovered 270 Aboriginal artifacts underwater off the country's northwest coast.

According to a July study, the artifacts were underwater because sea levels rose and submerged 30% of Australia's coast line at the end of the last Ice Age 12,000 years ago.

The researchers found stone tools for cutting and chopping, as well as stones for grinding seeds. The tools were at least 7,000 years old, and they're conclusive evidence that Aboriginal people flocked to the coast for food and resources.

"People gravitate to coastlines," Jonathan Benjamin, an archaeologist at Flinders University and lead author of the study, previously told Business Insider. "But if you want to know what was happening on the coasts, you now have to go underwater."

Read the original article on Business Insider