In 'Twin Peaks' season 2, the hero becomes a villain (and so do we)

Before I watched Twin Peaks, I already knew the major plot points. Like a lot of people, I first experienced the show via a kid-friendly parody — like The Simpsons or Sesame Street — and the series was on and off the air long before I was ready for it. By the time the show was readily available on DVD, I’d read about Twin Peaks and learned about its peculiar phenomenon: The stunning pilot, the tantalizing mystery, the general sense from the public at large that the show burned bright and then dimmed out.

This narrative was maybe always too simple, and you can throw it out the window now. Twin Peaks returns for a revival season on Showtime in a couple weeks. And the show’s initial run, so hard to find for years, is ludicrously available — streaming on Showtime and Netflix. And even knowing major plot points didn’t spoil my experience of watching Twin Peaks. The show’s uniquely unspoilable: Co-creators David Lynch and Mark Frost turned their small-town murder soap into a swoony, sensual, freaky-as-hell waking dream. You can explain how Laura died, and you can even try to explain why she died, but you can’t explain the damn-fineness of Twin Peaks‘ particular coffee.

You can watch Twin Peaks for the Laura Palmer stuff. It’s the central narrative through-line, what we now casually refer to as “mythology” because in our curious modern age even the gloopiest teen romances have mythologies. When David Lynch directed a Twin Peaks prequel film, Fire Walk With Me, he focused on Laura as a character and a symbol.

RELATED: Twin Peaks: 9 Exclusive First Look Photos

But there’s more to Twin Peaks‘ complicated legacy than Laura. The “more” is season 2. Jeff Jensen and I talk about the season in this week’s episode of A Twin Peaks Podcast: A Podcast About Twin Peaks, which you can listen to here right now!

I have no clue what it was like watching the second season of Twin Peaks when it was initially on television; I dug into season 2 after the Showtime deal went through, knowing full well there was more Twin Peaks on the horizon. What I found was a show split into four radically different directions, a tonal supernova struggling within and against the boundaries of ’90s-era broadcast television and the show’s own ambitions. You can split the season into four parts:

1. Trippy, semi-philosophical mid-century American myth recontextualized via freaky end-of-the-millennium paranoia and post-theistic spiritualism.

2. Skewed dark but intentionally satire of small-town life.

3. Shockingly un-quote-marked pretty-person primetime soap opera, essentially a slightly weirder version of Dynasty or Knots Landing.

4. Legitimately moving character drama.

Any of these shows would be a good show. When Twin Peaks season 2 is at its heights — in the episodes directed by David Lynch, or the trilogy of episodes focusing on Laura’s killer — it is all of those shows at once. And it is possible to feel frustrated with any of these shows. If you’re watching Twin Peaks on the assumption that the characters should be taken seriously, enjoy struggling through the subplot about Little Nicky, the Devil Child. If you’re fully engaged with the deep-weird supernatural elements of the show, theorize (in vain!) that Special Guest Star Billy Zane is the One-Armed Man’s cousin. If you badly want the show to be a sudsy primetime soap, you will absolutely love the arc where biker James gets embroiled in a murder plotline about a rich woman, her vain husband, and her devious brother-lover.

The dissonance is unsettling — and frequently fascinating. The death of Laura Palmer’s killer is a moment of radical symphonic cinema, complete with a biblical rain and a remarkably sincere vision of the afterlife. And in the episode after that moment — at that character’s funeral! — two wacky old brothers start squabbling, and one of the old men fall in love with a young redheaded sexpot, and then everybody falls in love with said sexpot. From mythic tragedy to randy-old-dude comedy soap, in no time flat!

Circa 1991, this probably played frustratingly for any viewer. In the context of TV drama circa 2017, it’s fascinating, a stylistic collide that few shows today would dare. Take, like, The Handmaid‘s Tale, maybe the best weird-unsettling-thrilling drama on television right now. The Handmaid’s Tale has a perfect control of its tone, capable of shifting from disturbingly close-by American dystopia to dark-humor trench feminism. You could even watch it with a shipper’s eye — Max Minghella, you work on that car — although that’s maybe missing the point. (Although maybe most shipping is missing the point — and I say that as someone who thinks half the Star Trek movies only make sense if Kirk and Spock are sleeping together.) I love Handmaid’s Tale. And it is impossible to imagine that Handmaid’s Tale would suddenly introduce a subplot where one character starts to restage the Civil War in their office, impossible to imagine that next week on Handmaid’s Tale someone will get amnesia and super-strength and join the high school wrestling team.

Maybe it’s an unfair comparison. Twin Peaks was always supposed to be a weird show full of weird people. And the joy of season 2 is how you can feel everyone involved in the show trying to figure out just what constitutes “weirdness.” Heather Graham joins the show late as Annie, a character who seems airdropped into the series to give Dale Cooper a love interest. Their flirtation is unsubtly romantic — they take a boat ride together, a Nicholas Sparks couple years before Nicholas Sparks started writing couples. But her backstory is tantalizingly strange: An ex-nun who attempted suicide, she’s experiencing the world from an almost newborn, innocent perspective.

“Innocence” is a thematic signpost on this show — it will either be lost, or it is already lost. The show ultimately ties Annie back to Laura Palmer, another blonde apparent innocent marked by malicious forces, and to Dale’s lost love Caroline. You imagine that a show constructed with streaming-era coherence would connect the dots more, but season 2’s slippery foundation rewards the attentive viewer. Is the show targeting Annie as a new victim? Is Dale drawn to her innocence — or is this the show indulging some baked-in Vertigo fixation, a running fascination with dead girls and the living women who remind Dale of dead girls?

Annie joins the show right as season 2 begins ramping up to its big plot-arc finale: The Miss Twin Peaks contest, an opportunity for all the actresses on the show to perform for the town. Miss Twin Peaks is either the most or least successful storyline of the second season. The season, in general, loses track of the major female characters on the show. Donna pines for James, Audrey pines for Special Guest Star Billy Zane, Lucy decides whether lovable Andy or endearingly caddish Dick will be the father of her child, Shelly leaves the diner and returns to the diner. And there are a few too many sexy-women-are-funny gags (see aforementioned redheaded gold-digging sexpot).

And the fact that Miss Twin Peaks just parades the women in an old-fashioned context feels retrograde. Until the big opening dance number starts, and the women are wearing cabaret outfits draped in plastic — wrapped in plastic, like poor dead Laura Palmer. By this point in the show, there’s a new villain in Twin Peaks, who’s planning something bad for whoever wins the pageant. It’s like the show is serving up a new victim. And the fact that Miss Twin Peaks is filmed wholly sincerely — there are dance numbers and meaningful speeches! —somehow makes it more disturbing.

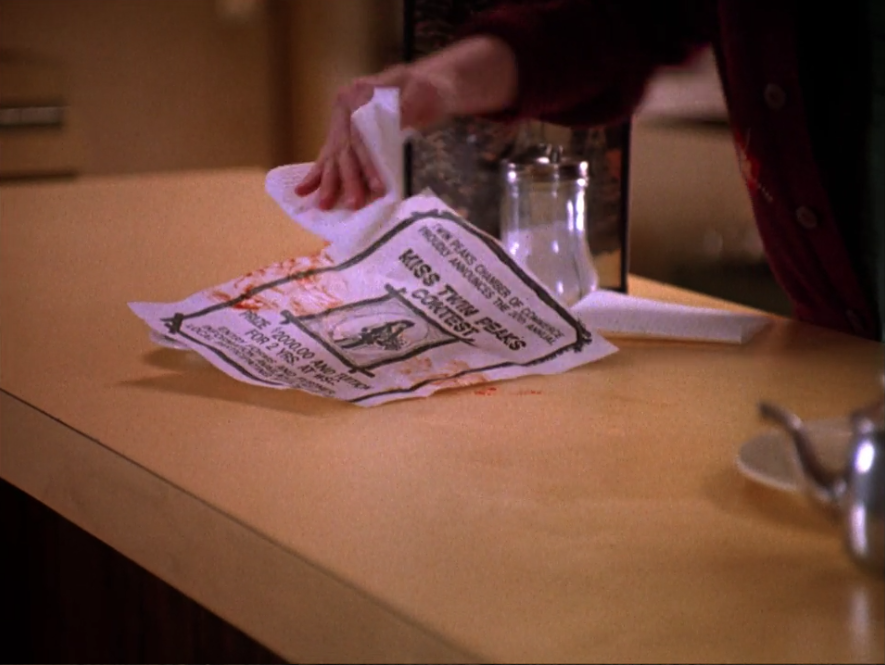

Further on this tip: My favorite scene of season 2 comes from the third-to-last episode, eventually titled “The Path to the Black Lodge.” It’s a stunning, casually horrific two-minute shot. By this point, Annie’s working at the diner and Agent Cooper is full in wuv. The shot begins on a paper advertising Miss Twin Peaks; the red is ketchup, but on Twin Peaks, red is never just ketchup.

Annie tries to clear up the debris — but a hand comes from offscreen, grasping hers. It’s a romantic gesture, but in context, it doesn’t quite feel that way.

“Couldn’t hurt to give it a shot,” says Cooper. He’s recommending that she participate in Miss Twin Peaks — and we don’t know it yet, but her eventual participation in the contest will lead her to something like doom.

Cooper sits down for coffee. They talk about St. Augustine and they talk about Heisenberg.

Initially, we hear light diner music on the soundtrack. Then, as the camera slowly moves back, the freakier tones of Angelo Badalamenti’s score come in. These two characters are flirting, talking about how much they have in common, forming a bond. They are so happy they can barely restrain themselves, but the tone of the scene is unnerving.

We catch sight of another customer. I initially thought this was the Log Lady, but we never see her face, and there’s no obvious log. Then again, the mere fact that a character who looks vaguely like the Log Lady is in this scene could be a choice — or it could be a mere weird coincidence. Cooper stands up and leans in for a kiss. There is finally an edit as they smooch — and then the loud sound of a crash. It appears that, by leaning in for a kiss, Cooper knocked over a coffee cup. In the world of Twin Peaks, there is no worse omen than wasted coffee.

There is a moment like this at least once in every Twin Peaks episode, even after the show “solves” the murder of Laura Palmer. (To the extent that that murder was ever actually solved.) There are obvious high points, and if you find yourself frustrated watching this season in anticipation of the upcoming revival, know that the second season finale is one of the most incredible and inscrutable episodes of television ever filmed: a hall-of-fame outing for director David Lynch, who seems to be simultaneously rescuing Twin Peaks and giving it an explosive Viking funeral. There’s also David Duchovny as Agent Denise Bryson, and truthfully I kind of love Little Nicky the Devil Child, and if you don’t love Lucy and Andy then you’re dead inside.

But without a doubt, Laura Palmer was the glue that kept Twin Peaks together. Without her, the show is off in a million directions. Yet as you look back over the season, you notice an interesting idea, occasionally explicit but more often a slow-burning revelation. Dale Cooper came to Twin Peaks as a wandering hero, investigating a murder and attempting to make right what had gone wrong. Does he become the show’s problem?

This is said explicitly by Jean Renault, one of the show’s many villainous Canadians, who thinks the town started to go downhill after Cooper arrived. Of course, Renault hates Cooper; the agent’s presence has run a train over the Renault family and their curiously elaborate (yet hilariously ill-equipped) crime empire. But Cooper-as-problem runs deeper as the show continues. The explicit “villain” of season 2 is Windom Earle, Cooper’s former partner — a character whose fascination with the occult mirrors Cooper’s. Both Earle and Cooper pursue Annie, the show’s final angelic blonde, one murderously and one romantically — the implication being, maybe, “are they really so different?” And Annie’s kidnapping is the plot motivation for both men in the series finale, which plunges both Cooper and Earle deep into the darkest mysteries of Twin Peaks.

By finale’s end, Cooper has been changed — a change that you can read any number of ways. But when I frame Cooper in the whole of Twin Peaks season 2, I’m reminded of the Nathaniel Hawthorne short story “Young Goodman Brown.” In the story, a typical everyman from Salem walks into a very Twin Peaks-y forest and experiences the very Twin Peaks-y revelation that all his fellow kind townspeople have a dark double life, worshipping Satan or some other dark un-Christian entity. Having been granted this revelation, Young Goodman Brown returns to the town in the daytime a changed man. He sees all the townspeople as they usually appear, good Christian people; he sees his wife, glowing and happy and running to kiss him. But he just looks at her sadly.

The easy read on this story is that it’s about maturing, learning the world isn’t what you thought it was, etc. But the story continues. Having returned to town, Goodman seems to hate everyone around him, can’t listen to them sing songs in church, doesn’t love his wife the way he used to, dies totally unhappy. According to scholars — or anyhow, my high school English teacher — the “problem” of this story isn’t that Goodman’s town is full of devil worshippers pretending to be Christians. The “problem” is that Goodman is the only one incapable of living with the full complexity of human experience: The awareness that who we are on the outside doesn’t capture fully who we are on the inside. Goodman Brown isn’t sad because his whole town is evil. He’s sad because he thinks he’s the only person who is truly good.

The implication of this read of the story is that Goodman can never take the final step into spiritual maturity: The acceptance that we are all evil and good, dual citizens of Lodges White and Black.

(NOTE: In an essay about Twin Peaks, the great Greil Marcus also referenced “Young Goodman Brown,” albeit with a different and much more intriguing layer of analysis. I didn’t read Marcus’ brilliant essay until after I started writing this, and it’s too late to restructure this essay around, like, “Rappaccini’s Daughter.” Now that I’ve made that dumb joke, I realize “Rappaccini’s Daughter” is an uncannily Lynchian story, what with its beautiful garden full of poisonous plants, a gorgeous innocent girl immune to the poison because she is herself poison, and the general implication that the romantic dude protagonist’s urge to “save” his lover is actually killing her.)

All to say: I wonder if Twin Peaks season 2 was, in some dark, rumbly way, building up to some greater complexity with Dale Cooper. Not necessarily that he was “bad,” but that his mere fact of investigating was stirring up greater forces than he could ever understand. (Recall: Cooper, talking to Annie about Heisenberg, creator of the Uncertainty Principle, the idea that the mere act of looking changes what you’re looking at.) And, on a deeper level, you can feel the show expressing some central frustration: The weird feeling that everyone, characters on the show and audience watching at home, misses the mystery of Laura Palmer. Is it possible to feel nostalgic for a dead girl? By the season 2 finale, the offering of a young woman has become almost ceremonial — an idea that goes supernova in Fire Walk With Me. Dale Cooper is the outside in Twin Peaks, fascinated by the town’s mysteries and tantalized by its curious charms. It’s not difficult to connect Dale’s own experience to we, the viewer, patiently passing time while we wait for a new murder mystery to unfold.

Was this a central idea of Twin Peaks — or one of many happy accidents, one more snowball rolling down season 2’s mountain of romances and transcontinental business deals and Civil War reenactments? We might have an answer when the show starts again on Showtime. Or maybe not — maybe, after a quarter-century, the new version of the show will leave Annie in the rearview mirror, with super-strong wrestling champion Nadine and Dale Cooper’s Lumberjack Outfit and the oft-resurrected Packard family. Either way, the second season of Twin Peaks has only gotten better. No longer a show-killing disappointment, it’s a fascinating look at a phenomenon struggling within itself.

And as the shining hero becomes his worst self, Twin Peaks becomes a mirror for our own fascinations and frustrations. And when that hero looks in the mirror, he shatters it. And so the show ends. For awhile.