Artists Face an Uphill Battle Against AI in Copyright Cases | PRO Insight

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

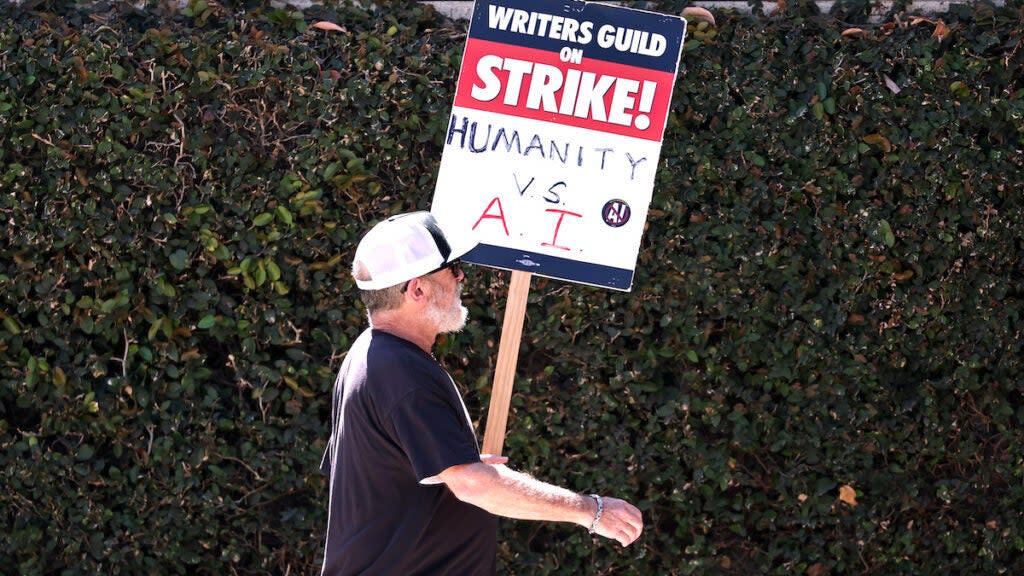

Let’s start with the good news for human creators. A federal judge in Washington, D.C. just upheld the U.S. Copyright Office’s policy that AI-only generated works cannot enjoy copyright protection.

Human creativity is “at the core of copyrightability, even as that human creativity is channeled through new tools or into new media,” District Judge Beryl Howell wrote. Her ruling Friday puts to rest, at least for now, fears in Hollywood that AI can displace writers to create commercially protected scripts. Why would studios and streamers go the AI-only route if they can’t protect their work product?

That’s the news on the output side of AI. But there’s less welcome news on the input side.

Back in January, I noted the initial round of inevitable litigation by copyright holders across the creative spectrum who claimed mass infringement by generative AI’s “training” on copyrighted works across the Internet, including their own. In one of the most closely-watched early cases, Andersen v. Stability AI, a group of visual artists sued the AI image generator and two other similar operations.

My question at the time: “Does this kind of generative AI infringe our copyrights, our exclusive ability to commercialize our works, on a massive scale?” I predicted that answers to that fundamental question would be coming soon to a courtroom near you — “This year, in fact,” I wrote.

Now one important early return is in, and it isn’t looking good for those visual artists in the Stability AI case — or the creative community in general. Federal Judge William Orrick, who sits in Northern California’s hotbed of creativity, was demonstrably skeptical of those artists’ infringement claims, signaling in court that he was inclined to ultimately dismiss them.

Orrick pointed to what he deemed to be the small number of each individual artist’s creative contributions included in the AI training set of 5 billion images, a number that came from the artists’ pleadings. Yes, there may be some technical infringement here, but that impact is de minimis.

The judge’s comments to the litigants mean that he’s likely to find that the AI’s “scraping” of copyrighted works and its resulting output of imagery constitutes a transformative fair use. Orrick has yet to publish his final decision on the matter, and he’s likely to give the artists a chance to bolster their case, but his words leave little doubt as to where he will land. No amended pleadings will change his fundamental math. And if Orrick ultimately rules this way, then it’s a near certainty that he will also dismiss the artists’ separate state right of publicity claims. How could commercial opportunities for their artwork be adversely impacted by generative AI models that spit out novel images based on their training on billions of works?

But what if that number is 5 million instead? Or 500,000, 5,000, 500 or 50? Would that smaller level of AI training be deemed de maximis instead?

And what about the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent bombshell decision in the Warhol Foundation case? There, the 7-2 majority shocked many by looking past the precedential history of the infringement-exempting doctrine of transformative fair use to focus instead on whether Warhol’s artwork competed directly for commercial opportunities with the unlicensed photograph on which it was based. The Justices ruled in the photographer’s favor based on their perceived adverse impact to her livelihood. Should their reasoning impact Judge Orrick’s in his Stability AI case?

And should the specific creative medium matter when mass AI training on copyrighted works is alleged? Arguably, AI’s novel visual art outputs compete less directly with the unique styles of the artists who are scraped than is the case when AI is used to generate novel photorealistic images based on the libraries of Getty Images and others. Getty Images, in fact, just happens to be litigating its own closely-watched infringement case against Stability AI.

Let’s go back to federal Judge Orrick’s numbers game. At a minimum, it seems rather obvious that his entire analysis should change if an AI generates art “in the style of” a particular artist. That smacks of direct competition a la Warhol, no matter how big or small the training set. But can we be sure?

That’s the thing about the law that is discussed too little. While the legal system strives to portray itself as being a beacon of clarity and certainty when confronted by novel issues, making them appear to be black and white, the reality is much different. The law is mostly gray. I am an intellectual property lawyer by trade and also clerked for the chief federal judge in Hawaii, so I’ve seen this firsthand.

Court rulings are a series of subjective judgment calls by very non-AI human beings who frequently aren’t particularly well-versed in the specific issues at hand, especially when confronted by entirely new transformational technologies like AI. Judges are typically generalists, and no two judges will rule in precisely the same way, or even take the same approach in analyzing an issue.

But here’s the thing. Early cases in any new technology-laced litigation that affects the creative community always have outsized impacts. They become precedents, guidance for other courts to follow, especially when they come from federal courts that generally hold more weight than the state courts. In the case of claims of AI infringement of creative works, those rulings become even more potent when they come from federal courts that sit in California, the world’s center of gravity when it comes to the world of entertainment.

When he issues his final ruling, which will come soon, Judge Orrick will literally lay down the law on the fundamental question of whether AI inherently infringes on copyright when it trains on a multitude of creative works. Assuming he rules as anticipated, it will be up to other courts faced with similar issues to at least strongly consider his conclusions, if not be fully bound by them. Those courts will further flesh them out, based on their own level of tech prowess and individual biases. And ultimately, these thorny copyright issues likely will find their way to the U.S. Supreme Court just as they did in the landmark Betamax case of 1984, when a majority of the Justices in a 5-4 decision ruled in favor of Sony and found that the recording — or “time shifting,” as the court called and rationalized it — of copyrighted works did not constitute infringement.

Jurists in the future, just like Judge Orrick, certainly will search for some semblance of unattainable certainty as they make their own AI rulings in the months and years ahead. But in those courtrooms, only one thing will be absolutely certain. In a world of fast proliferating AI-driven copyright infringement litigation, lawyers will be fully employed to happily argue each side — at least until AI inevitably starts creeping in and infringing on their turf, too.

For those of you interested in learning more, visit Peter’s firm Creative Media at creativemedia.biz and follow him on Twitter/X @pcsathy.

The post Artists Face an Uphill Battle Against AI in Copyright Cases | PRO Insight appeared first on TheWrap.