Author and Veteran Elliot Ackerman Reflects on the War That Defined His Generation

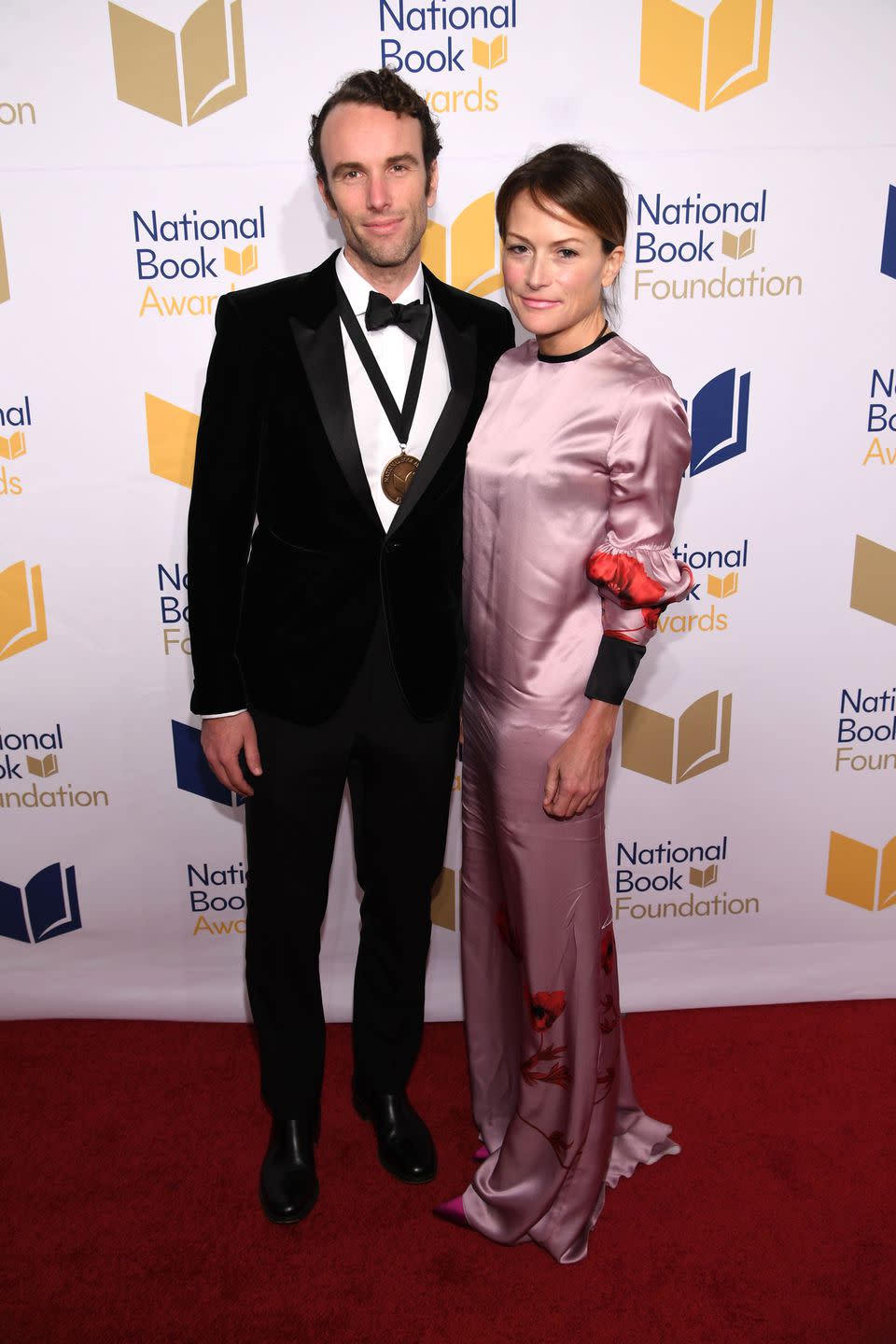

Elliot Ackerman's eight years of service in the U.S. Marine Corps have come to a close, but there's no end in sight for his literary excavation of the war. Beginning in 2003, Ackerman served five tours of duty in Afghanistan and Iraq, where his tremendous leadership during a month-long battle in Fallujah earned him the Silver Star and a Purple Heart. Those harrowing experiences informed Green on Blue, his 2015 novel about an Afghan orphan, and Waiting for Eden, his 2018 novel in which a grievously wounded soldier considers the point at which a life is no longer worth living. In 2017, Ackerman was nominated for the National Book Award for Dark at the Crossing, a complicated love story about radicals and refugees in war-torn Syria.

Ackerman's latest work is Places and Names, a multi-faceted memoir of the battles he fought, the ties that bind us across cultural divides, and the ongoing work of confronting the ghosts that never leave us. Esquire spoke with Ackerman about the generational weight of war, the necessity of finding purpose after serving, and the traditions through which memories of the dead are kept alive.

Esquire: At one point in the book, you write, “When you are a young man, and your country goes to war, you’re presented with a choice: you either fight or you don’t. And you’ll always remember what you choose. I don’t regret my choice, but I maybe regret being asked to choose.” Walk me through your choice to fight. What was going on in your life and in the world when you enlisted, and what compelled you to do it?

Elliot Ackerman: I came into the military in 1998, so pre-9/11, and I joined by what I would say is a confluence of three forces. The first is that I spent a good chunk of my youth growing up outside of the United States. I think that gave me an appreciation or a different context of what it meant to be an American, and it made me feel like a wanted to give something back. I also wanted to just have a job where, whether I was good at my job or bad at my job, the job mattered. I was young, and I felt like I would get that experience in the Marines. I was also one of those kids who never stopped playing with G.I. Joes, so I had that innate interest in the military. That guided me down the path of joining the military, but I came in during peacetime. While I was in the ROTC in college, 9/11 happened, and everything became very, very real. What I mean by that, “You’ll always remember whether or not you served,” is that wars are often generationally defining. And so, as much as we are all defined somewhat by the generation into which we were born, if you were a male in the generation (at least in times past), the question is, “Did you serve in the war?” If you’re of the Vietnam generation, did you fight in Vietnam, or did you not fight in Vietnam? If you’re of the Second World War generation, did you fight in WWII or did you not fight in WWII? I don’t say that to place a value judgement on it, per se, but it’s just one of these binary things, generationally. When the war started, I still felt as it was going on that it was something I wanted to participate in-I wanted to be there and fight.

ESQ: Have you ever encountered anyone who chose not to fight and regretted that?

EA: I don’t think I’ve met people of this war who said they didn’t fight and regretted it because it defined our generation to a much smaller degree. With the First World War, there’s this idea that you had a lost generation, and I don’t think you’d ever say that about my generation. But I think you could say there is that lost part of a generation-that there was a part of our generation for which this was defining. I’ve had people come up to me and say, “I wish I’d served. I wish I had that experience.” People who are middle-aged or older. And I’ve seen in my own family, with grandfather and my father, how the wars were more defining for their generation. There’s also this idea of regretting being asked to choose. We did go to war, and if there’s something I could take back, I wish that I had been able to join the Marines, and that we’d ended up staying in peacetime, and that none of these things would have happened. I wish that our leaders had been able to navigate the shoals of war and peace more successfully. But I certainly don’t regret my decision to join the Marine Corps.

ESQ: Speaking of leaders navigating conflict, elsewhere in the book, you write, “Bush imagined Iraq as if it were France in the Second World War, as if the Iraqis were just waiting to be liberated. That’s what many Americans thought.” Is that still your take on the political situation, or has more time and distance from active duty changed your view?

EA: When I wrote that, I was thinking of these larger ideas of, ‘What is the U.S.’s relationship to war?’ I’d say the American birth story is the Second World War. That’s the modern nexus of American greatness. I actually have a copy of the Iliad I was issued in college, and the cover photo, with no explanation, is a photograph taken by Bob Kappa of American soldiers hitting the beaches on D-Day. In a sense, World War II is our American Iliad. The American century begins there. I think sometimes it’s difficult for Americans today to disintermediate our reflexive relationship to war from this Second World War narrative. We’re always saying, “When are we going to bring the troops home?” Well, we never brought the troops home. The troops are still in Europe, ever since the Second World War. We have bases all over Europe, and American troops are the ones who ensured the peace after the Second World War, until the Berlin Airlift in the Cold War. Same thing on the Korean peninsula. When you look at it, the only wars where all the troops have come home have been disastrous wars like Vietnam. I’d also say Iraq in 2011, to some extent. That doesn’t mean you can be fighting the war forever, but where do we get this conception that there's a hard termination to a war, that everybody comes home? That’s never been the case, but I think that viewpoint is informed by our Second World War perspective.

ESQ: I was charmed by the tidbit in the book about the twin buildings that you named Mary-Kate and Ashley. How much is humor necessary to survive in a combat environment, and how do you find ways to laugh when there’s not much to laugh about?

EA: I think humor is a huge part of war because there’s all this tension. You need it to go somewhere, and the place that it often dissipates to is humor. It’s every little thing, like naming the buildings that way to gallows humor. We often had a saying when I served in the military, that our job was too serious to take it seriously. You’d go crazy if you took it seriously. You had to view the absurdity in things just as a survival mechanism.

ESQ: You write early in the book of Abu Hassar, a man you met in a refugee camp who fought for al-Qaeda, “Maybe he, like me, has become tired of learning the ways we are different. Maybe he wishes to learn some of the ways we are the same.” As you spent time in the Middle East and got to know the people there, what did you discover are the ties that bind us, even across religious and cultural divides?

EA: That returns us to this idea that that warfare is a generational experience, which doesn’t just go for the generation of one country. It goes for the generation of all the participants. What I recognized in my relationship with Abu Hassar, who had fought for al-Qaeda, or even my friend Abed, who’d been a democratic activist in the Syrian revolution, was that those conflicts, which I would argue were all interrelated, were the defining events of our twenties and thirties. I would say those conflicts were generationally defining for all of us, and in that way, we were similar. As we grew older and recognized the significance of those events with the perspective of time, we began to want to understand those events from every vantage point possible, which included the vantage points of the people who had been our antagonists. We could see that there were many ways we had been similarly defined. Someone like Abu Hassar, who fought in Iraq at the same time as I did, in the same places that I did-I feel that I have more in common with Abu Hassar than many of the people I grew up with who didn’t go to the wars.

ESQ: There’s a moment where you describe a soldier marching for the Islamic State as, “glamorizing his appointment with history.” What leads a soldier to think that way? Is it the nature of jihad, or do American soldiers sometimes think this way, as well?

EA: Everybody thinks this way. There’s a quote I love by Timothy Page, one of the iconic Vietnam War photographers. He said, “Take the glamour out of war! I mean, how the bloody hell can you do that? Go and take the glamour out of a Huey, go take the glamour out of a Sheridan. Can you take the glamour out of a Cobra, or getting stoned at China Beach? It's like taking the glamour out of an M-79, taking the glamour out of Flynn. It's like trying to take the glamour out of sex, trying to take the glamour out of the Rolling Stones." We don’t talk about it, but there are parts of war that are glamorous, that are exciting. There’s a part of it that’s incredibly seductive. There are parts of it that are horrible, but there are many, many parts that are very seductive. In that piece of the book when Abed is reciting his poem, “I Have a Date With History,” and he’s talking about fighting with the Free Syrian Resistance, what I’m writing about is that as much as he was glamorizing what the Free Syrian Resistance meant to him, there were probably a group of Islamic State fighters sweeping into Mosul and heading towards Baghdad feeling that same sense of historical significance and glamor. That has always existed in war.

ESQ: That gets me thinking about war in popular culture. It’s a self-perpetuating cycle, in a way. It’s not just that war is inherently glamorous, as you say, but that as we raise our young people on a diet of popular culture about war. In a sense, we’re conditioned to find it glamorous.

EA: Totally! It’s this incredible irony. In the Marines, we had uniform standards, and there were things we weren’t allowed to do. You’re not allowed to write on your helmet. You have to wear your uniform a certain way. I remember at a certain point in the battle in Fallujah, I looked over, and one of the guys in my platoon had a royal flush in his helmet. At another point, they were all wearing their ammunition belted across their chests like Pancho Villa. I realized that they were acting out their fantasies of what they thought it was to be a Marine in wartime, and their fantasies were informed by movies like Platoon and Full Metal Jacket-except, those were just movies. In the future, if someone ever made a movie about them, they would be making a movie about the movies. There’s this very strange cultural feedback loop that exists around war, and those movies, ironically, are anti-war movies. If you talked to anybody in film, they’d say these are anti-war movies, but they’re viewed by people going off to war as very exciting movies. The way war plays out in culture is multidimensional and pretty fascinating.

ESQ: You wrote about someone you served with named Doug, who argued that killing isn’t wrong when it’s for a purpose. You wrote, “The years of combat to follow made more sense when you held on to those kinds of precepts, when they felt true.” Are there other precepts you held onto, and were some of them harder to believe than others?

EA: Doug was a person who was, in many ways, free of irony, who believed with a high level of purity in what he was doing, and subsequently what we all were doing. Over years of war, years of being away from your family, years of seeing friends get hurt or killed, it’s easy to start asking questions. Appropriate questions, but to really be questioning what you’re doing. Sometimes, if you’re still doing it, and you still believe in it, and you feel all those doubts, it’s reassuring to look at someone like Doug, who believed in what he was doing with such clarity. He was always a force for clarity in my life when there were so many countervailing forces that were more ambiguous and caused me to doubt.

ESQ: In another part of the book, you write about a Kurdish man, and you discuss the complexity of being a friend of the United States. You write, “I wonder if we Americans are living up to our end of the bargain as friends.” What makes being a friend of the United States complex?

EA: The nature that alliances are complex-that, when it comes to issues of war and peace, nations act in their own best interest. As long as interests are aligned, the possibility exists for friendships, but when interests are no longer aligned, you can see how the United States has historically abandoned certain allies. These Kurds in particular have been a staunch ally of the United States and the region for a long time. As of this moment, that position is in jeopardy, because there are certain things that the United States wants to get done in the region, mainly extricating itself from the region, which will very much be done at the expense of the Kurds. It can be dangerous to be an ally of the United States, but what we often fail to anticipate is the long-term consequences of abandoning our allies, whether it’s the Hmong hill-people in Vietnam to the mujahideen fighters we supported in Afghanistan after the Soviets left, to the Shiites who supported us in the first Gulf War, who then rose up against Saddam Hussein and then were massacred without our intervention. So, the historical antecedents of U.S. alliance followed by betrayal are long, and often times it can be dangerous to be our ally.

ESQ: Did you ever feel a cognitive dissonance between the political messaging you received from your superiors and your own lived experience of the on-the-ground reality?

EA: It’s a real politique. It’s famously been said that war is politics by different means, and you certainly feel that when you’re on the ground and encounter uncertainty. Much or most of your job does not involve high-level, kinetic war-fighting operations, but sitting down and drinking tea with people, and explaining to tribal leaders why their interests are best served by aligning with the United States. The history of U.S. alliances is full of duplicity, and that doesn’t help your case when you’re trying to encourage people to enter into those same alliances. But I’ve never looked at it from a moralistic vantage point, because I think anyone who’s spent much time in a war understands that nations behave in their own best interest, and all actors on the battlefield are usually behaving in their own best interests.

ESQ: How often do your memories of your time at war come back to you, and in what sort of context do they arrive?

EA: People often ask me, “How do you feel like the war has changed you?” They ask me to disintermediate the parts of me that are the wartime parts from the parts that are the peacetime parts, the non-war parts, and it’s very difficult for me to do that, because the war was really the defining event of my adult life. For the better part of a decade, I was at war. It’s tough for me to say how the war might have changed me, because the war made me. It’s not like I sit around thinking about it all day, but for instance, it’s D-Day. I woke up this morning and dropped my kids at school, and was sitting down at my desk when an old friend of mine who’s still in the military texted me a bunch of photographs of him parachuting into some of the old drop-zones in France. He had been invited to do so as part of the celebration. I don’t know if that’s me thinking about the war, if he and I are wartime buddies, or if it’s just me living my life, where that part of my experience is intermarried with my life.

ESQ: In the book, you allude to the incredible things that Marines do for one another. Can you elaborate on that?

EA: What I mean specifically by that are the greatest acts of heroism that I’ve seen. Ultimately, the impulse that drives Marines to perform such heroic acts has been an impulse to try to help a friend. It gets to this root idea of, “What is courage? What causes someone to do something brave?” I think that oftentimes, courage isn’t an emotion-somebody’s brave, but courage isn’t an emotion. Nobody feels courage. I could tell you I’ve certainly felt fear. I’ve felt very, very afraid at times, but I’ve never felt brave. So, that begs the question: What is the opposite emotion? What is the emotion that inspires courage? I would say that that emotion is love. Love borne out of friendship, and love borne out of a relationship that Marines have with one another by the time they go to war-because you’ve both known each other for a long time before you get deployed. Every bit of real courage I’ve felt on the battlefield was ultimately inspired by this love.

ESQ: Of your repeated deployments, you write, “My youthful desire to matter and make a difference had eroded if it wasn’t gone altogether, so, why did I keep deploying? Was I drawn back to war because I couldn’t find meaning outside of it?” What was that struggle like for you in between deployments?

EA: We talked a bit about Doug Zembiec. When I talked about him, that was someone who felt great clarity over these issues of why he was doing what he was doing. And for me, there would be this pull and push. On one hand, I liked the job that I was doing, even loved the job sometimes, and the people I did it with were my very best friends on earth. But, at the same time, I was asking myself questions. “Why am I doing this?” “Is this going to get me killed if I do it for twenty or thirty years?” “What would that all be about?” So, it’s doubt. The more you do it, the more people you see get wounded and killed, the more doubt starts to seep in. I think those questions become natural.

ESQ: How do you make meaning in a lasting way after the war or your involvement in it has ended?

EA: I think for anyone to be happy, you have to have a sense of purpose. I think that what happens with the people who go to war at a relatively young age is that you eventually develop an almost dysfunctional relationship with purpose, because the purpose you have during wartime is extremely intense. At least at the tactical level, you need to have a relatively clear mission, and you’re trying to do that mission with people who become your very best friends. Eventually that ends, and you come home, and in order to be happy, you have to repurpose yourself. What I’ve seen in veterans I know who’ve done well in the military and transitioned into another life with relative ease is that they have found another purpose that’s able to fill them. The people I know who’ve really, really struggled are the ones who have a hard time figuring out what it is that they want to do next. They have a hard time feeling that same level of intensity. I think it’s very common. We’re all trying to find our purpose, but what I think can be challenging for someone who’s been in the war is that you have had this incredibly intense purpose against which you’re measuring everything else.

ESQ: At the end of the book, you annotate the summary of action that led to you being awarded the Silver Star for your service in Fallujah. I found that very moving. What do those official records tend to leave out?

EA: I’ve read many summaries of action, and I’ve written many of them. They leave out the personal reflections, which is what I wanted to add-the real color and feel of what those words mean when somebody writes down what happened in a combat incident. You can say what happened after: “So and so sustained serious wounds.” Or, “So and so ran up to the roof under fire.” But what do those wounds look like? What does it feel like to run up to the roof under fire? What are people saying? Who are the people engaged in this? I’ve had that summary of action document for years, and I’d obviously read it over a few times. As I was putting together this book, it originally wasn’t in the book at all. My editor told me, “We turned in the book,” and he said, “You know, you don’t ever write really in detail about what happened to you, and that’s the question people are going to have.” And he said, “You can put it in the book or you can leave it out, but I’m just going to tell you that, as your reader, that’s the question I have. You need to decide whether or not you want to include it.” So I had this document, and I’d always felt that this document was a little bit incomplete, so the way I decided to talk about it was to fill in the gaps on this one document.

ESQ: How did you explain the war and your involvement in it to your children when they were young? As they grow older, will that explanation change or evolve?

EA: I think they understand that that’s a part of who Daddy is. I certainly don’t want that to be all of who I am to them. For instance, I have lots of war memorabilia that I’ve accumulated- photographs, plaques that have been presented to me, stuff like that-and I’ve found intuitively that I don’t hang it up around the house. You come to my home or my apartment, and that is not what’s on the wall. But when they become curious about it, and if any of them ever decide that they are interested in possibly serving, I would just want to explain what it is. I’d just want to make sure that they really understood what they were getting into, and then they can make their decision for themselves. I will say, the one thing that I do in fact do with them that’s probably very specific to having a veteran as a dad is that they live in Washington D.C., and, so, on Memorial Day, we go to Arlington. I’ve every year done that with them, and I walk in front of all of the graves, and I tell them all the stories about my friends, because my hope is that they’ll remember doing that, and that they might remember those stories and tell them later on. That’s something I do for my kids, but also as a tribute to my friends. If a story about them can be remembered by my kids, maybe they’ll be remembered for a long time.

('You Might Also Like',)