How The Damned took four days and lots of cider to kickstart a revolution

You’d hardly know it was there. Unprepossessing, you might call it. A converted workshop in a tiny alleyway in suburban Islington, Pathway Studios promises a ‘small and busy’ space for up to eight musicians. There’s a square room the size of a modest kitchenette. And, at six-and-a-half feet wide, a control booth that’s positively Lilliputian by comparison.

It’s late September 1976 and shoehorned inside are four young upstarts from London, a producer still in the midst of learning the ropes and a modest tangle of recording gear. Newly signed to Stiff Records – the pioneering indie label set up Jake Riviera and Dave Robinson – The Damned have just finished cutting their debut single, a startling shot of pure adrenalin called New Rose.

“We didn’t have a clue what we were doing,” remembers drummer Rat Scabies. “Or whether it was going to be loved or even listened to. But the first playback was one of those moments you never forget. It just hit the spot and captured a moment. It was like taking off in a jet.”

New Rose was released a month later. It may not have troubled the charts, but it heralded a new era. Urgent, primal, unstoppable. New Rose was the first recorded acknowledgement of punk, a form of music that aimed to sweep aside everything in its path. Or at least cause a fair bit of bloody mayhem trying.

The Damned were punk’s prime movers. The Sex Pistols and The Clash may have been more fêted by press and public alike, their reputations funded by major labels and massaged by calculating managers, but The Damned repeatedly beat them to the gate. They were the first to release a single, the first to tour the US and the first to release an album. They weren’t the most proficient of players, but God, were they effective. And nothing illustrated that more explicitly than their debut LP from early 1977 – Damned Damned Damned.

So just who the hell were The Damned? Revisionist history tends to portray punk as the result of a single glorious Big Bang that happened sometime in 1976. But the truth was much more ambiguous. All of the new breed of British musicians looked to the past for inspiration. The Damned’s songwriter and guitarist Brian James had grown up in thrall to the Pretty Things and The Yardbirds, before discovering US underground legends like The Stooges and The MC5. As a Crawley teenager in the early half of the 70s, he’d formed his own band – Bastard.

“We couldn’t get a gig here to save our lives,” he explains today. “No one had heard of Iggy & The Stooges and the only band in this country who had any kind of attitude was the Pink Fairies. Otherwise it was people like Genesis and Emerson, Lake & Palmer or glam rock, which seemed very thin. So I ended up in Belgium for a couple of years, playing with Bastard.”

Another Fairies fancier was Captain Sensible, whose other great love was The Groundhogs. Then known as Ray Burns, Sensible was guitarist for Croydon-based proto-punks Johnny Moped.

“One of our first gigs in the Croydon area was at the Beaulieu Heights festival, an open-air park gig,” he says, “and the reviewer said that I played with a ‘punk sensibility’. And we’re talking 1974 or something. The Moped band had bags of attitude. We didn’t give a flying fuck about anything.”

When James returned from Belgium in late ’75, The Damned began to slowly take shape. “I answered an ad in Melody Maker,” he says. “They actually mentioned The Stooges and were looking for a drummer and guitar player, so I went down there.” The band was London SS, headed up by a pre-Clash Mick Jones and Tony James, later of Generation X. The drummer who answered the call was Chris Millar, aka Rat Scabies, who’d previously played for the Surrey-based outfit, Tor.

“Tony and Mick wanted to be in Mott The Hoople, because that was what they looked like – leather trousers, frilly shirts and very long hair,” recalls Scabies. “But Brian just stood out. He had really spiky hair, drainpipe jeans and pointy shoes. He was fucking great and played great. He and I just hit it off.”

Around the same time, Brian James saw his first Sex Pistols gig. “That made me realise that London had changed in the two years I’d been away,” he says. “There was definitely a smell in the air, suddenly there were people you could relate to.”

There followed another short-lived band called Masters Of The Backside, overseen by local scenester Malcolm McLaren, which featured Chrissie Hynde, Scabies and his co-worker in Croydon’s Fairfield Halls, Captain Sensible. But James, Scabies and Sensible had bigger plans.

“We’d go into Bizarre Records in Paddington,” says Rat, “and look at copies of Punk magazine. There’d be pictures of The Ramones, Blondie, Television and Richard Hell and you’d have to guess what they sounded like, because they didn’t have any records out. The rest of the people in the music establishment were still listening to Yes and Jeff Beck and all those muso-based players. But none of them were really doing anything that meant much to an 18-year-old kid in London.”

All they needed now was a singer, someone who looked the part. Cue a trip to London’s Nashville Rooms to see the Sex Pistols in April ’76. “There were two guys in the audience who looked like they had something about them,” says James. “One was Sid Vicious and the other was Dave Vanian. We went up to them both: ‘Look, we’ve got a rehearsal next Thursday, come on down and try out as our singer.’ And Dave was the only one to turn up, so that’s why he got the job. We couldn’t wait around for anybody.”

The Damned’s first proper gig was as support to the Pistols at the 100 Club on July 6, 1976. At that point, the word ‘punk’ had yet to gather weight.

“The funny thing was that of all the bands who were around, what became the class of ’77 if you like, none of us were using the ‘p-word’,” says Sensible. “I’d be talking to Malcolm McLaren or the people who went on to form Generation X and The Clash; none of them thought of themselves forming a punk group. It was only people like [journalists] Caroline Coon and Giovanni Dadomo who grouped us all together.”

Ever the opportunists, The Damned soon found a kindred soul in Jake Riviera at Stiff. “Jake and Dave Robinson were kind of DIY, make-it-up-as-you-go-along people,” says Sensible. “That’s what I liked about Stiff and that’s how we beat the Pistols. We signed with a proper indie punk label while everyone else was waiting for the big bucks.”

James remembers being instantly struck by Riviera’s attitude. “He just knew about things,” he explains. “He was into The Stooges, The MC5, Richard Hell and The Heartbreakers. And he looked like one of us. So we did the single. It was Jake who really plumped for New Rose, and I remember having a copy in my hands and thinking: ‘If it all stops now at least I’ve got a great single to show for it.’ Then he said: ‘Look, how about us managing you and putting out an album?’ Of course we all jumped at it.”

But not before they took their place on the ill-fated Anarchy Tour of December 1976, a nationwide jaunt organised by Sex Pistols manager McLaren and The Clash’s guardian, Bernie Rhodes, who also invited along Johnny Thunders and The Heartbreakers. On the back of the furore caused by the release of Anarchy In The UK – issued four weeks after New Rose – and the Pistols’ potty-mouthed appearance on Bill Grundy’s Today_Show, all bar three of the dates were cancelled. The Damned were booted off the tour even earlier though.

“We were expecting to get kicked off anyway,” offers Scabies. “There was an obvious animosity between Jake and Malcolm. We were only on that tour because we’d been gigging a lot and sold tickets, whereas nobody had seen the Pistols before the Grundy show.”

Undeterred, they headed back into Pathway Studios in January ’77 for their debut album. A head-spinning blast of noise, Damned Damned Damned found the band tearing through a dozen songs in just over half an hour. It was utterly devoid of any of the preening rhetoric of The Clash or the Pistols’ misanthropic bile. Instead it was a riotous explosion of fun. Speed was key, in more ways than one. “I’ve honestly smoked less spliffs than Bill Clinton,” claims Sensible, “but we used to do a bit of sniff and we had a few nosebleeds too. For a fast-paced punk set, it seemed to suit it all quite well.”

Alongside New Rose, there was the irrepressible Neat Neat Neat and sinister beauties like I Fall, Born To Kill and So Messed Up. Feel The Pain alluded to illicit bouts of S&M, while Fan Club examined the wobbly lines between band worship and manipulation.

Produced by Nick Lowe, conventional wisdom has it that the album was all done in 10 days. “Ten?” snorts Sensible. “It was done in four. The music was boshed down onto tape in two and the mixing lasted another two days. I didn’t actually see Nick do anything, other than send out for bottles of cider. But he had the right idea. The way to produce The Damned was not to fucking produce us! That was the masterstroke. The guitars don’t sound good at all, they’re in your face and distorted to fuck. For me it encapsulates everything that punk should be. It’s raw and lo-fi, but also gloriously exuberant and fun and exciting. It’s just a succession of great riffs.”

James is similarly keen to flag up Lowe’s role. “He captured our live sound and I can’t imagine anybody else getting it better than that. We’d go in to start, then the first thing Nick would say was: ‘Right, let’s go down the pub!’ He’d get us all loosened up, then we’d go back to the studio and bang it down.”

Lowe’s great gift, by all accounts, was knowing when a track was nailed. “We hardly did many takes at all,” recalls Scabies, “though I think we ended up doing New Rose two or three times. I listened to the multi-tracks not so long ago and at the end of the take you can hear Nick come in and say: ‘At last!’ Which I remember thinking was very ironic at the time.”

The second single, meanwhile, remains a favourite of Scabies. “Neat Neat Neat always stays with me,” says the drummer. “There’s something about it that nothing else has. And the other song I really love is [Stooges cover] I Feel Alright, just for its purely chaotic, destructive sense of fun.”

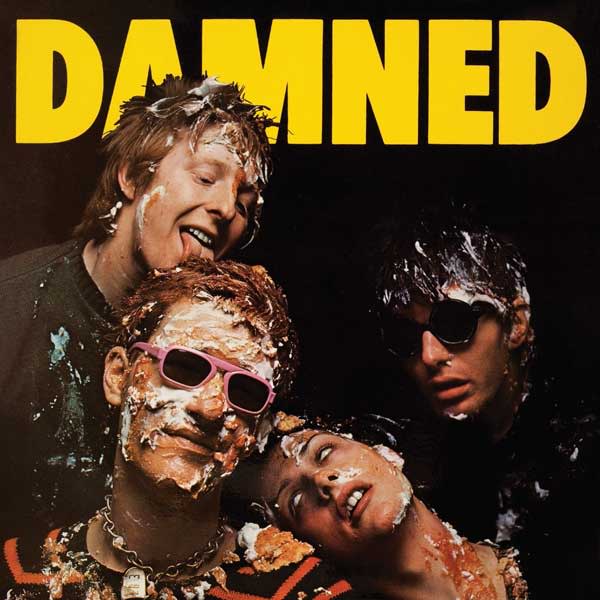

That same sense of merriment extended to the album cover itself. Not for them the blank-generation stare of their more earnestly self-conscious peers. The front of Damned Damned Damned finds the foursome in the aftermath of a pie fight. It might have been a real-life episode from The Beano, or a still from a rowdy school trip in Please Sir!, but it was entirely apposite for the band. “None of us knew anything about it,” says James. “It was a conspiracy between Patti Palladin and Judy Nylon, with photographer Peter Kodick, who was married to Patti. I was going out with Judy and they concocted this little plan.”

Sensible: “Patti and Judy made the flans and poured in the shaving foam with the baked beans and all the rest of it, then threw it all at us. I was very pissed off because I never thought we’d make more than one album and you couldn’t see my face on the front cover!”

Adds James: “It sort of destroyed everything that had gone before it, in a sense. No one wants to look shitty on their own album sleeve.”

Damned Damned Damned was released on February 18, 1977 – Brian James’s 22nd birthday. It was duly lavished with praise by the band’s main cheerleaders, Sounds and Melody Maker. By the time it peaked at No.36 in April, The Damned had left for their inaugural swing around America, having just toured the UK first as headliners, and then as support to Marc Bolan’s T.Rex.

“It was so funny because the album came out and we only had those songs,” explains the Captain. “Quite often we’d find ourselves having played a gig and the club manager would say: ‘Sorry, I can’t pay you because we booked you for an hour and you only did 25 minutes.’ So we’d go back on and play the whole album again. People would be looking at each other and going: ‘What the fuck’s this?’ What we were doing was so different that we used to drive people to the door. At one show in High Wycombe, we whittled it down to four people.”

“I remember one gig where the Captain drove all the people out because he did nothing but complain about beards and facial hair and hippies,” laughs Scabies. “And we did another one in Luton to a crowd that didn’t know what to do with us. They wrote to Sounds that week, saying that Brian James played like he was wearing boxing gloves, which of course Jake immediately blew up to poster size and put on the wall at Stiff. People were sort of bemused, some of them got it and some didn’t. But on the nights they got it, that’s when I started thinking that perhaps we were doing something right.”

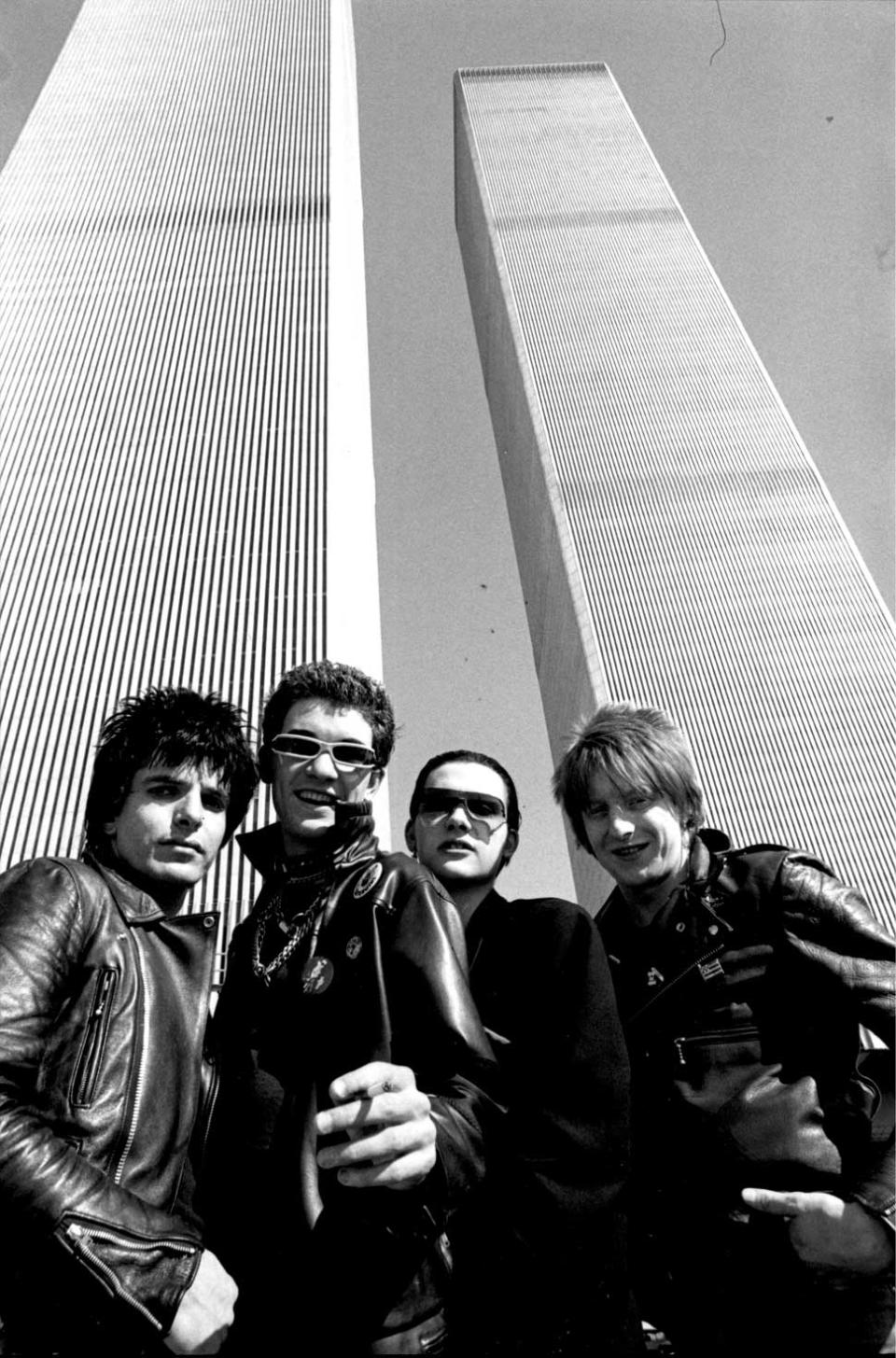

The US gigs proved a triumph, especially the opening three-night stand at CBGB. One reviewer proudly proclaimed it as ‘The Day Punk Arrived In America’. Back home by May, The Damned immediately set out on the road again, this time with another of Stiff’s new charges, The Adverts.

Punk was by then very much part of the modern lexicon, though it didn’t always rest easy on the tongue. Perhaps the most infamous gig on that tour took place at the Drill Hall in Lincoln in mid-June.

“I’ll never forget that night,” says Scabies. “The local authorities and the local football hooligans decided that punk needed a good kicking. At the end of the night there was a very large mob outside the venue, trying to break down the doors and turn the whole place over, including us. They trashed all the vans while the police just sat watching. But our tour manager was an ex-paratrooper called Big Mick and knew what was coming. He bolted the doors while bricks were coming through the windows. Then he arranged us all in a line: ‘If they come in, nobody run.’

"I was standing next to Gaye Advert and holding a mic stand, with Tim [TV Smith] on the other side of her. It was the most useless line of defence you could imagine, but Big Mick’s military training paid off. Once they saw we were ready for a fight and had some heavy equipment, they were off. But that was the general public’s feeling about punk. Even the police and authority figures had somehow worked out that we deserved it. If you didn’t toe the line you were regarded as an outcast. There was no place for you anywhere.”

The dawn of The Damned had been one constant mad dash, and by the end of the year the strain was beginning to show. Midway through a European tour in September, Scabies announced he was quitting. His final recorded contribution was on Music For Pleasure, the band’s ill-starred, Nick Mason-produced second album, which lacked the fire and brevity of The Damned’s classic debut.

“There were so many internal problems by then,” Sensible declares. “It was such a dark time. We were all at each others’ throats and were heading into what I affectionately term the Chaos Years.”

James sounds rueful when he talks about the album. “Rat decided he’d had enough and we just weren’t the same band anymore. Plus the punk scene was becoming a parody of itself. What were once symbols of rebellion had just turned into a uniform. The leather jacket and the skull ring didn’t mean a damn thing anymore. The third generation of punk bands were just imitators.” By February 1978, The Damned had split.

The band’s legacy as punk progenitors, meanwhile, seems to be a confused one. Maybe it’s the cartoon capery, maybe it’s the myriad changes of personnel and style. Or just the plain old fact that they’ve lasted this long. Whatever the reason, peers like the Sex Pistols, Buzzcocks and The Clash are regularly garlanded with more kudos than The Damned.

“The Damned have almost become a by-line,” admits James. “It’s like The Beatles and the Stones with the Pretty Things. For a lot of people the Pretty Things were the real deal. They were dirty, had the longest hair and played their R&B in the most we-don’t-give-a-fuck way. And I think the same thing has happened to The Damned.”

And what of that first album now?

“The original idea was to be noticed,” concludes Scabies. “And we did that alright. I think record companies felt threatened by us and we put paid to a lot of shitty bands. But we never set out to influence people or change anybody. We were just grateful to be given a shot.”

The original version of this feature appeared in Classic Rock 173, published in 2012.