Getting better: 5 ways the Beatles can help improve your guitar playing

The Beatles are the most recognisable band of all time. Their music has stood the test of time for seven decades. They were at the forefront of the rock revolution of the 1960s and they paved the way for many musicians to follow in their footsteps – especially guitarists.

Even though the band's recording career lasted less than a decade, their influence has remained strong to this day with modern bands still quoting the Fab Four as an influence on songwriting and techniques.

Through their stellar catalogue of music, there are so many lessons we as guitar players can learn and use in our own playing. In this lesson we’re going to talk about five things you can learn from John, Paul and George to put to use right away.

Check out the video and follow along with the tips below on subjects including chord progressions and fingerpicking.

1. Using the relative minor for contrast

When writing a song, having contrasting sections is important because this is one trick that hooks the listener in and keeps their attention. Contrast also allows a song to move through different moods and emotions.

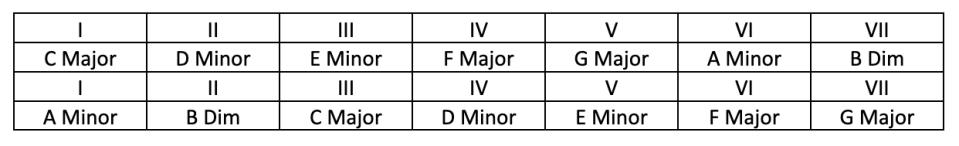

One thing the Beatles did to create this effect is to switch to a relative key for a section change. In this example, we’re going to use the song Misery from 1963 Please Please Me. This song is in the key of C Major. All keys have a relative key which means it shares all the notes/chords with another key. C Major’s relative key is A Minor. These two keys share the same notes and chords:

Although both keys share the same chords, the emphasis is on the I chord, this is the chord that gives the key it’s overall identity. If your progression focuses on the I as a major chord, the progression feels Major, if it emphases the I as a minor chord, the opposite is true.

We can use this as a turning point in a song to keep the overall key and chord sequence intact, but change the mood of the song.

In the song Misery, the verse progression uses the chords C, F and G, but the chorus switches to Am, C and G. This change creates a contrasting section that takes on a different feel.

2. The minor IV chord

If you want to add a little bit of excitement into your major chord progressions, you can take a leaf out of the Beatles and add a Minor IV chord. This is a chord that is not usually found in a major key, but introducing it can be a really great way to spice up a chord progression.

This works great in slower songs, such as the classic In My Life.

This song is made up of an A Major (I), E Major (V), F#m (VI) and D (IV), but after the D chord, there is a brief move to the Dm (Minor IV) before returning to the root.

While the Minor IV chord does not necessarily fit into the key, it can be a great passing chord on the way back to the root. It creates a moment of tension before resolving back to the I chord.

3. Outlining a chord progression

If you are playing in a two-guitar band, or just want to write two guitar parts that weave in and out of each other, you can learn a lot from the Harrison/Lennon approach.

In the song I Saw Her Standing There, you can hear two different guitar parts that are both different, but complementary to each other.

One guitar is playing a I IV V progression using E7, A7 and B7 chords while the other is playing two different parts over the progression. The first part is an E7 triad without the E note, mixed with a simple lead lick. The second part is a walking blues style riff that frames the chords being played by the other guitar.

In isolation, both parts are very different, but when overlaid on each other, they create a really interesting sound where one guitar plays the straight chords and the other frames the progression with other voicings or single notes.

Using deceptive cadences

Sometimes when you hear a new song for the first time, or you write a chord progression on your guitar, you may have a sense of familiarity even if you’ve never heard or played that particular piece before. This is cause by our ears recognizing things in the composition that it deems familiar.

This is usually chord progressions. As we found in our study of Taylor Swift's hit songs, we have these, and specific chord resolutions and movements that we hear in most of our favourite tracks. Our ears become tuned to hearing these things.

If you want to add something to a song that breaks this familiar feeling, you can use a deceptive cadence. This is when we bring a new chord into the progression that does not belong to the progression before resolving it back into the progression that we expect.

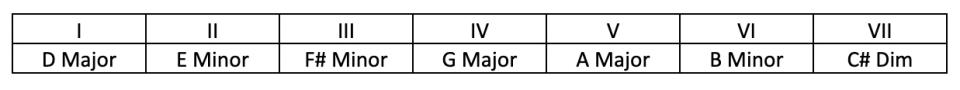

In the Beatles track P.S I Love You we hear this in action. The track is in the key of D Major, so we expect these chords:

For the most part, this is what we get. However, before the track goes to the C, you’ll notice an out of place Bb Major chord being played. This would be a bVI chord, which is not part of the major key of D major. This borrowed chord creates a feeling of tension before going back to the C chord which we expect to hear.

A deceptive cadence is a great way to attract some attention to a part of a song by making the listener really aware that something has changed. This doesn’t just work with a bVI chord. You can try this with any chord that is not part of the key you’re playing in.

5. Paul McCartney's Blackbird fingerpicking

The picking pattern for the song Blackbird is probably one of the biggest Beatles riffs that people play wrong. Often notated as entirely fingerpicked, this classic track is actually played by Paul McCartney with a really unique fingerstyle approach.

Rather than picking every single note, the pattern utilizes single-picked notes along with micro strums with the index finger.

The pattern can be broken up into two halves. The first half involves playing the A and B strings with the thumb and index finger at the same time. Then you play the G and B strings with the index finger in a mini downward strum motion, before up picking the single B string with the same index finger.

The second half starts with the A string being played with just the thumb, the B string being picked with an index finger upstroke and ending on an index finger downward, micro strum of the G and B strings.

This rhythm can be applied to other chords and used in your own songwriting to create some fast-paced feeling fingerstyle riffs and progressions. Try it with some open and barre chords and feel the driving energy that it gives your own chord progressions.