LGBTQ+ Contestants Say ‘American Idol’ Failed Them: ‘I Saw the Worst of It’

ZACHARY TRAVIS DIDN’T KNOW what American Idol was when he auditioned in 2005, because he had spent most of the past decade in a youth correctional facility. Inmates there weren’t allowed to watch television, he says, except on the day of the September 11 attacks. But Travis — who was first incarcerated at the age of 11, for reasons he’s not yet ready to discuss in a public forum — found strength in Christina Aguilera’s ballads of self-love. He says that he connected with the “pain, sorrow, and heartache” in the singer’s octave-defying voice. “Every day I would sing in my cell,” Travis recalls. “I thought I was a good singer.”

After being moved to a residential reentry center at the age of 16, Travis began working at a Colorado grocery store, where his supportive coworkers suggested he try out for the megahit reality competition show, which was holding auditions in Denver. He thought it was the perfect opportunity to return the gift that pop music had given him by being an inspiration to others.

More from Rolling Stone

Simon Cowell Doubts One Direction Will Reunite, Wishes He Could Still Profit Off Band's Name

Maren Morris Comes Out as Bisexual: 'Happy to Be the B in LGBTQ+'

Travis wasn’t aware that he couldn’t carry a tune until his audition aired on TV a year later, in January 2006. Seated in the living room of the same halfway-house counselor who had driven him to the audition, he thought to himself, “God, I do suck.” But the realization was too late. His phone was already being blitzed with calls, first check-ins from friends and family members and then requests for interviews with People and Us Weekly. Soon after, Travis says the LGBTQ+ advocacy group GLAAD (which did not respond to a request for comment on this story) telephoned with the offer of taking action against Idol on his behalf. He thought to himself, “What the fuck did I just do?”

The public reaction to Travis’ off-key rendition of Whitney Houston’s 1993 single “Queen of the Night” is perhaps most succinctly summed up by the title of a YouTube video of the tryout: “American Idol Audition Boy or Girl.” Travis wore bell-bottom jeans in a feminine cut and a white tank top to his audition, pulling his wavy blonde hair behind his ears. Simon Cowell, infamously the harshest critic among the show’s original trio of judges, appeared horrified by the sight of Travis, his mouth agape. After Randy Jackson, the panel’s swing vote, kicked things off by asking the contestant to say “something interesting” about himself, Cowell asked, “That’s necessary, is it?” Cowell proceeded to stop Travis in the middle of his performance, which he called “confused.”

Travis has come a long way since Idol. After pivoting to a successful career in gay porn under the name Kirk Cummings, he retired from the adult entertainment industry and now works as a dog groomer, a profession he finds peaceful. But even 19 years later, he finds the footage of his audition tough to watch. As he left the studio in tears, editors added the theme music to The Crying Game, the 1992 film that uses the sight of a trans woman’s body to shock viewers. Today, Travis presents as male and uses masculine pronouns, but at the time of his audition, he had hoped to someday transition. He even had his new name picked out: Kelly. When he was incarcerated, others would try to dissuade him from pursuing a future as a trans person by telling him that it’s a “really hard life,” and Idol seemed to prove them all right.

“I thought, ‘Wow, if this is how my life’s going to be, then I don’t want any part of it,’” he says. “My experience is not the normal experience of a trans person, but because I had chosen to be on a television show, I saw the worst of it.”

Open cruelty is no longer part of the Idol brand, now that the show is in its second run on ABC after Fox canceled the long-running program in 2015. The series, like much of contemporary reality TV, now trades on positivity, and the annual tradition of airing bad auditions has long been discontinued. But during the height of its popularity in the 2000s, schadenfreude was a major part of the show’s appeal. While launching the careers of instant household names like Kelly Clarkson and Carrie Underwood, Idol was also the show where tens of millions of viewers watched Cowell tell Season Three contestant Heather Piccinini that she’s “ugly” when she sings and belittle Season Five’s Crystal Parizanski for overtanning; he even pulled Parizanski’s mother into the room to humiliate the contestant further. The show’s June 2002 premiere, in which Cowell advised a young woman to sue her vocal coach, made it clear what Idol would be selling.

That feed-them-to-the-lions approach made Idol the number-one program on TV six years running, the longest stretch at the top in broadcast history — but the show tended to prey on its most vulnerable contestants, perhaps unwittingly. Idol producers were forced to issue an apology after Cowell compared Season Six hopeful Kenneth Briggs, who has facial malformations due to Aarskog Syndrome, to a “bush baby.” Season Five’s Paula Goodspeed took her own life outside judge Paula Abdul’s home in 2008 after Cowell criticized the contestant’s metal braces following a performance of the Creedence Clearwater Revival/Ike and Tina Turner standard “Proud Mary.” Goodspeed was reportedly an obsessive stalker who changed her given name in tribute to Abdul, and the contest judge publicly criticized Idol’s producers for not doing more to protect her, saying she alerted them to Goodspeed’s behavior prior to the audition. (A spokesperson for the show did not comment on Abdul’s accusation at the time.)

Among those most targeted by Idol’s alleged abuses were anyone who was outside of the norm, as defined by the extremely narrow standards of Bush-era popular culture. This often included contestants who were experiencing mental health issues, individuals with disabilities, people of color, and plus-size singers like the late Mandisa Huntley, the Season Five contestant of whom Cowell infamously asked: “Do we have a bigger stage this year?” But Idol enjoyed a particularly contentious relationship with the queer contestants who hoped that the series would offer their big break into an unforgiving industry, many of whom had only started to come to an understanding of their LGBTQ+ identities. In another exchange condemned by GLAAD, Cowell told Travis’ fellow Season Five hopeful Charles Berry, who now is an out gay man, to shave off his beard and “wear a dress,” saying that he would make a “great female impersonator.”

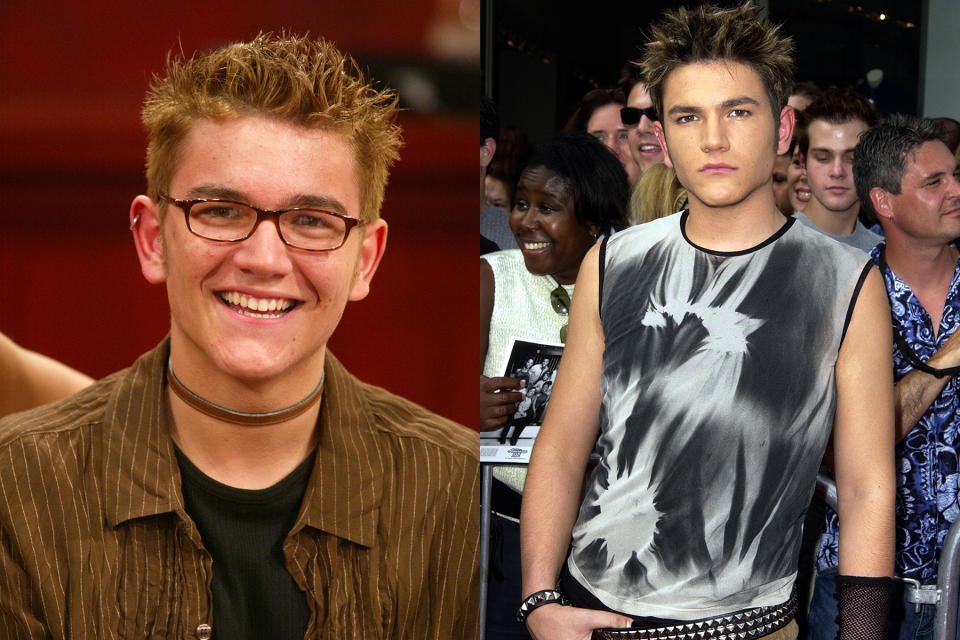

Keith Beukelaer, whom Cowell famously called “the worst singer in the world,” knew immediately after his Season Two audition that it would end up being broadcast. “It’s something that I don’t know if I ever fully recovered from,” he says. “I remember it as if it was yesterday.” A devoted Madonna fan, he performed “Like a Virgin” in a green mock-turtleneck sweater, gyrating his body in sync with the song’s suggestive lyrics. Beukelaer has come to understand himself as having Asperger’s Syndrome, although he didn’t have the language for it at the time, and he came out as gay a few years after appearing on the program. He still struggles with the notoriety that his brief appearance on Idol brought, the decades of mockery that followed six minutes of air time.

Cowell did not return multiple requests for comment for this story. Neither did Jackson, longtime host Ryan Seacrest, or Idol creator Simon Fuller — who based the show off his own U.K. series Pop Idol, which aired from 2001 to 2003. But a source close to the production, who requested not to be named in this story, defended the show by affirming that “every single person who came on Idol, whatever their race, color, creed, or sexual preferences, was placed squarely in the firing line for Simon’s barbed critiques.”

Beukelaer found some vindication 11 years later by auditioning for Cowell’s other singing competition, The X Factor, where he earned unanimous yeses from the judges’ table following a rowdy performance of Sir Mix-a-Lot’s “Baby Got Back.” But regarding the question of what made his earlier audition catnip for Idol producers, Beukelaer admits it was likely a combination of factors. “They knew I was different,” he says. “Everybody seemed to know that I was gay. I mean, I was a guy singing Madonna. It was the song choice. It was the dancing. It was my sexuality. It was the fact that I’m on the spectrum.” Beukelaer wishes that he knew then what he knows now but, being just 19 years old at the time of his tryout, he feels he was young, naïve, and didn’t fully understand what he was getting himself into: “I wasn’t expecting it to be that bad.”

WITH AMERICAN IDOL wrapping its 22nd season on May 19, Rolling Stone spoke to 18 of the show’s queer contestants about its complicated relationship with the LGBTQ+ community. Some describe their time on Idol as idyllic, the fulfillment of everything they ever hoped it could possibly be. Clay Aiken, the Season Two runner-up, began dating his first boyfriend on the show. Aiken says he wasn’t even out to himself when he auditioned for Idol, having seen so few glimpses of LGBTQ+ life outside of TV shows like Ellen and Will & Grace that being a proud, gay man didn’t seem like an option. Behind the scenes of Idol, he found, queer people were thriving, working as production assistants, members of the security team, or in the makeup department.

Aiken and his boyfriend, who was a member of the crew, would remain together for another two years after the season wrapped. The producers didn’t know about their relationship at the time; he says the first person he ever told he was gay was his best friend on the show, Kimberley Locke, who came in third in their season. But to this day, Aiken credits Idol not only for introducing him to his first love but also for giving him the space to figure himself out. “If I had not done Idol, I don’t even want to claim that I would not have come out,” he says. “I hope to God that I would have, but I certainly would not have found that on my own for many, many more years.”

What was a queer paradise for some, however, was a nightmare for others. Of those who spoke on the record, many say that Idol effectively forced them into the closet, and they believe it’s because the show was fearful that an openly queer contestant would alienate the show’s largely conservative viewership. An Experian Simmons survey conducted in 2010, the last year that Idol topped the Nielsen charts, found that the series was the fourth-most popular show among Republicans; it didn’t even rank among Democrats, who preferred cable prestige dramas like Mad Men and Dexter. Accordingly, Idol didn’t have an openly LGBTQ+ contestant for another four years after that survey’s release. (Season 13’s MK Nobilette, an out lesbian with a Justin Bieber haircut, auditioned in 2014 with a powerful take on “If I Were Your Woman” by Gladys Knight and the Pips. She made the Top 10.)

There was no rule saying that queer contestants couldn’t discuss their personal lives, but some singers say that Idol made it clear that some things were best kept secret. R.J. Helton, who uses they/them pronouns, went back into the closet and started dating a woman before they auditioned for Idol’s first season, hoping to make their family happy. Helton’s parents always envisioned that they would become a pastor or a Christian music artist, and when Helton’s boy band, the Soul Focus, went their separate ways, competing on Idol felt like a logical next step. Having recently broken things off with their fiancée, not wanting to live a lie, Helton began seeing their Idol stand-in during the season. Although they kept the romance a secret from producers, Helton says the other contestants knew. “None of them cared,” they say. “It was the first time that I felt accepted by a group of people.”

Idol producers never found out about the relationship, but the stakes were nonetheless made clear when executive producer Nigel Lythgoe, the show’s most influential creative voice, pulled Helton aside after seeing them exchange a friendly peck on the cheek with a male member of the crew. “Listen, we love you,” Helton says the producer told them. “We think you’re great, but let’s continue on the sweet side, with the Christian boy thing.” In their on-camera interviews and stage performances, Helton says they tried to tone down their natural ebullience, “butching it up” and staying as quiet as possible. A team of publicists, they recall, followed Helton everywhere “because they didn’t want me to break character.”

In an email to Rolling Stone, Lythgoe asserts that he “never stopped any contestant from coming out” and says he “never would have done so.” “I did work with a number of individuals who, sadly, were struggling with issues around coming out, and I provided feedback that was very common at the time: that they should let their talent do the talking and not allow others to denigrate them based on their personal lives,” he says. “If anyone was hurt by my advice on those issues, I can only apologize, but I only ever wanted to help and support the wonderful young people who competed on the first seasons of Idol, several of whom, tragically, were torn between a desire to live their truth openly and a great fear about how they would be treated on returning home by their families, by their communities, and even by God.”

Helton, now with the clarity of hindsight, wishes they’d had the confidence to present their full self to America. After being dropped from their record label following a 2006 interview in which they came out as gay, Helton recently came to the realization of their nonbinary identity. “I know it was a different generation, but there are parts of me that think: ‘If I could have worn a gorgeous evening gown with a full beard, I could have won,’” Helton says. When producers would tap them on the shoulder to remind them, “Hey, we don’t talk about this,” it made Helton scared of losing the only affirmation they’d ever had. “As a young person, that really plays with your psyche, especially when you’re not used to the spotlight, loads of fans, or the money. You just do what you’re told. I don’t know if that’s selling your soul to the devil, but it did feel like that. They lifted me up, put me on a pedestal, and told me that the pedestal will only be there as long as I play this part.”

Helton’s fellow Season One cast member Jim Verraros has spent years in therapy working to unlearn many of the unfortunate lessons he says Idol taught him, namely that it wasn’t OK to be himself. That education began with the Pygmalion-esque makeover given to the show’s aspiring superstars: Idol immediately traded in his nerdy aesthetic — wiry glasses and jean jackets with the collar popped — for a generic rock look, sleeveless vests with leather cuff bracelets. He got contacts, lowered his voice half an octave, and put away what he calls the “theatrical and stage part of me that comes also from having deaf parents and being expressive.” “It comes at a cost,” he says. “When you’re told that you aren’t enough — or that this version of you doesn’t work — you spend a big part of your life taking parts away from you so that you can achieve those dreams.”

Although Verraros made the Top 10 of his season, he struggled with the role created for him, and the miscasting of a nebbishy gay Midwestern boy as a conservative-friendly heartthrob led to friction with the show’s creative team. Former co-host Brian Dunkleman, who emceed Idol’s first season alongside Ryan Seacrest, says he overheard Cowell and Randy Jackson discussing plans to directly target Verraros, hoping to get a strong reaction out of him that they could film. “We’re gonna nail Jim,” he recalls the judges saying as they were having coffee in an Idol break room. Cowell tended to reserve his harshest critiques of the show’s inaugural cast for Verraros, and following that discussion, he told the contestant live on air, “I think if you win this competition, we would have failed.”

Idol did get the emotional reaction it sought from Verraros in a scene that ultimately landed on the cutting-room floor. Prior to the announcement of the season’s Top 10 finalists, Dunkleman says that Cowell informed the contestants they would be using the “judges’ veto” to oust one of them from the show. “Jim, you’re out of the competition,” Cowell told Verraros, prompting the young singer to burst into tears. (That’s when Dunkleman recalls that Lythgoe came over and instructed everyone to sing a modified version of the Monkees’ “Daydream Believer” to brighten Verraros’ spirits. “Cheer up, sleepy Jim,” fellow contestants sang together in unison.) For reasons that are unclear, Lythgoe opted to backtrack on the judges’ decision, Dunkleman says, allowing Verraros to move forward to the next round after all. “Later that night, I was at dinner and I got a pretty frantic message from Nigel saying, ‘Look, there’s been a change. Jim is back in the competition. Just please don’t tell anybody about anything that happened today,’” Dunkleman remembers. “And then the next night he made the Top 10.”

Those incidents, Dunkleman adds, played a major role in his decision to part ways with Idol, calling the program “evil.” He also recalls that a judging panel needed to be refilmed so Cowell could call Helton a “loser” instead of a “monkey.” “That’s what it was,” he says of Idol. “It was about how mean they were. It was about how shocking this was and how much they were making fun of these singers.” He isn’t sure, though, why the show singled Helton and Verraros out in particular. “Is it conscious targeting or is it subconscious? That kind of undertone, maybe they weren’t even aware of it.”

When presented with the anecdote, Lythgoe says that he chose to have Verraros reinstated to the cast “after Fox had suddenly asked us to cut someone.” “I believed passionately it was the public’s vote that decided who would leave the show and not the judges,” he says in an email. “Fortunately, Fox eventually agreed and Jim was reinstated.” He adds that he does not recall directing the other contestants to console Verraros through song.

After being voted off the show, Verraros found his own way through unconventional means. Making history as the first post-Idol contestant to openly acknowledge their sexuality, he released two favorably reviewed independent records, 2005’s Rollercoaster and 2011’s Do Not Disturb. Verraros went on to appear in the first two installments of the Eating Out comedy series, a gay softcore take on American Pie. After a 12-year hiatus from music, Verraros returned to the studio last year for the glossy pop track “Take My Bow,” which reached the Top Five of the U.K. dance charts. After so many years, he says that creating music again has allowed him to rediscover those aspects of himself he put away long ago. “I’m glad to see that it didn’t go to waste, that it wasn’t for nothing,” he says.

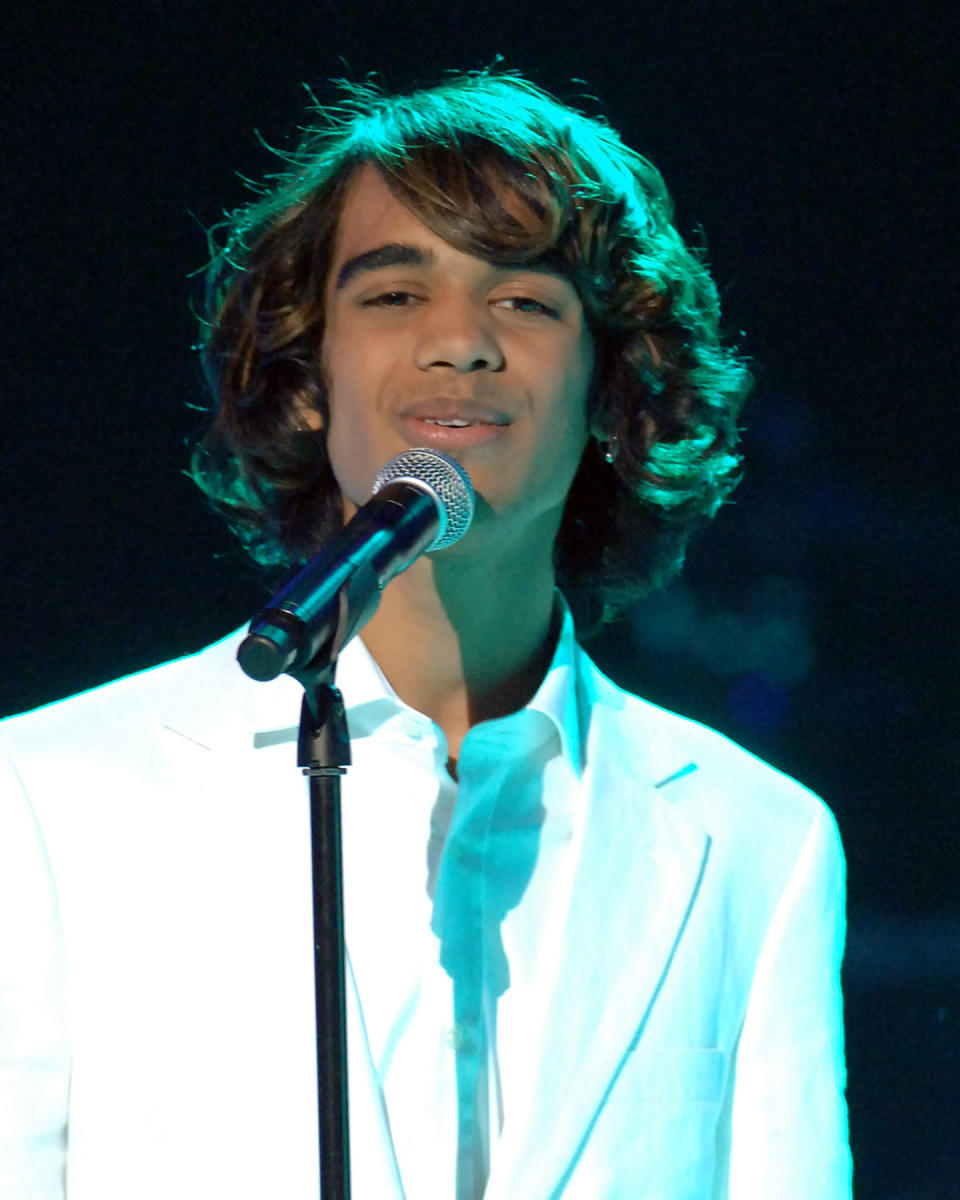

AMERICAN IDOL often strained to fit queer contestants into an instantly recognizable mold that producers could market for the widest possible audience. Simon Cowell declared that he would quit the program if Sanjaya Malakar, an affable Season Six hopeful with a perpetual smile, won the competition. Malakar, who is half Bengali and performed with the Hawaii Children’s Theater during his time living in Kauai, was unlike any singer the show had ever seen. He was earnest and goofy, striding up to the judges’ table to dance with Paula Abdul during a performance of Irving Berlin’s “Cheek to Cheek.” He also straddled the lines of gender, flat-ironing his chameleonic locks for a winsome cover of John Mayer’s “Waiting on the World To Change.” After weeks of all but begging viewers to vote Malakar off the show, Cowell commented regarding the latter song: “Maybe it’s your hair that’s keeping you in. I don’t know.”

Malakar came out as bisexual many years after Idol was over, finding himself after taking a job at a karaoke bar in New York where he found freedom in anonymity. What was hardest for Malakar to navigate, he says, was not the constant scrutiny from Idol’s judges but the vitriolic reaction from fans. A MySpace blogger vowed to stop eating until Malakar was sent home, although the contestant outlasted the hunger strike, which ceased after 16 days. The website Vote for the Worst, which urged fans to subvert the Idol system by keeping on its quirkiest and most divisive contestants, took up Malakar as a personal cause.

Looking back, Malakar believes that it’s the ambiguity of how he presented that bothered people so much. The judges and viewers just couldn’t figure him out because, as a 17-year-old kid who hadn’t graduated high school yet, he hadn’t figured himself out. “There was no way to really understand how to define me,” he says. “They didn’t know what culture I was. They didn’t know what sexuality I was. They didn’t know what genre I was. I was this anomaly that made people uncomfortable.”

The queer singers who had the most painful time being reshaped by the Idol system were those who stood out the most, whether they were flamboyant and over-the-top in their performance style, like Malakar, or their gender presentation skewed toward the effeminate. Season Eight runner-up Adam Lambert — who declined to speak for this story, citing his shooting schedule for The Voice Australia, on which he is a judge — has said that queer contestants who didn’t have the ability to hide were used by Idol as “comic relief.” “Anytime someone came on the show that was perceived to be gay or it was obvious enough that they were gay, they were a joke,” he remarked to the British music magazine NME in a 2018 interview. He added: “To be fair, some of them weren’t great singers, but there were a couple of really good singers that came on. And they weren’t taken seriously.”

To illustrate his point, Lambert noted the example of Adore Delano from Seasons Six and Seven, who would later contend on the reality competition show RuPaul’s Drag Race. Delano declined to participate in this story, but in a 2023 Instagram video publicly announcing her transition, she said that she went back into the closet to compete on Idol. Appearing on the show led her to suppress her transness in order to present herself as “something that was so uncomfortable,” she recalled. And yet her effervescent femininity couldn’t be contained: During her second appearance on Idol, she performed a sassy rendition of “Jailhouse Rock” by Elvis Presley that Cowell deemed “hideous” and “verging on the grotesque.” Delano was ultimately eliminated from the Top 16 after a performance of Soft Cell’s queer anthem “Tainted Love” that Cowell declared “absolutely useless.” She dyed her silky hair purple for the number.

Like Delano, Atlas Marshall auditioned for Idol twice, making it to the Top 36 in Season Eight and then trying out again for Season 16. Both experiences were extremely fraught. Following a performance of Meat Loaf’s “I’d Do Anything For Love (But I Won’t Do That)” during her first appearance on the show, Cowell looked at Marshall and remarked, “I think you probably would.” Even as a guileless 18-year-old with frosted emo bangs and angel-bite piercings, Marshall realized it was a “loaded comment.” “The joke around that song is that it’s about anal sex,” she says. After the audience booed Cowell’s remark, Ryan Seacrest, then the show’s sole emcee, invited Marshall to come sit on the judge’s lap, but Paula Abdul intervened and beckoned the contestant to rest on hers instead. Marshall was voted off Idol the next day.

Being spat out by Idol on her first go-around coincided with an already challenging time in Marshall’s life. She was living in a hotel after aging out of the foster care system. Marshall’s mother had recently been arrested and was incarcerated at the time of her audition. In her place, Marshall’s aunt and grandmother were in the studio audience to hear Cowell refer to her Meat Loaf cover as “excruciating,” although her grandmother appeared unfazed by the criticism. “I liked it,” she said with a shrug when Cowell asked what she thought of the number. Marshall’s mother, who recently passed away, was a lesbian, and she raised her child in a queer household where it was OK to be “open, flamboyant, and fabulous,” as Marshall recalls. Being taught by Idol that the outside world might mock the parts of herself she was taught to embrace was a rude awakening. “For so long, there was a lot of shame around it,” she says of her first Idol experience. “I felt gross. I didn’t like myself.”

Marshall felt she was due for a redemption arc eight years later, in 2017, when she learned that Idol was holding auditions in Portland, Oregon, practically down the street from her. The geographic synchronicity felt like an act of kismet: She had recently started transitioning, presenting more femininely and wearing makeup, and wanted the chance to introduce America to the woman she always had been. After making it past the initial round of tryouts, Marshall says she flew to New Orleans to sing directly for the new batch of judges tapped for the ABC reboot: Katy Perry, Luke Bryan, and Lionel Richie. But despite presenting as a woman during the audition, Marshall says producers made her dress as a boy for her on-camera interviews and called her a “drag queen.” Although she got three yeses from the panel, Marshall was cut before the next round, and the footage never aired. Adam Sanders, a drag artist who performs under the name Ada Vox, would eventually make the Top 10 that season.

While the team behind Idol’s current iteration did not offer a comment on the record, the source close to the Fox production contests the idea that the show stopped contestants from expressing their most authentic selves, while adding that “coming out might have damaged certain contestants’ chances for success.” “No one ever prevented anyone from doing so, but there was often a sense — right or wrong — that it would be better if the American public’s vote was based more on their judgment about the performers’ talent rather than their sexual orientations,” the source says.

It took years for Marshall to work through the trauma of her experience, she says, but she’s in a better place now. She has begun recording music on her own terms and hosts weekly karaoke nights in Portland, where she has finally found her family in the city’s thriving queer community. What Marshall is still working on, though, is letting go of the idea that she should feel appreciative for being given an opportunity from Idol or that she should be thankful for feeling manipulated and exploited. When she would tell others about what she went through, Marshall says people sometimes responded, “Well, that sounds ungrateful,” or told her, “You signed up for it.” “That’s what reality television is. I get it,” she says, before adding: “I didn’t sign up for years of emotional trauma. I signed up because I wanted to sing.”

TO DATE, a queer contestant who was out during their time on the program has never won American Idol. Samantha Diaz, who performed under the name Just Sam, casually acknowledged their queerness in an interview with the New York Post following their Season 18 win in 2020. “I am a child of God, so that’s always gonna come first,” they told the outlet. “That’s actually the only label that I ever want to have. But I like what I like, and that’s just that, you know? And it’s not men. Like, at all.” (Diaz, who performed as a subway busker in New York before winning Idol, made an appearance on the recently concluded 22nd season after being forced to go back to street performing to make a living.)

Although it would feel convenient to point the finger solely at Idol, the show at its peak reflected America’s culture as much as it defined it. When the series premiered in 2002, polling from Gallup showed that 43 percent of the U.S. populace still thought homosexuality should be illegal; Lawrence v. Texas, the Supreme Court ruling that struck down sodomy laws in the 14 states where gay sex was still illegal, wouldn’t be issued for another year. A majority of Americans wouldn’t support the right of same-sex couples to marry until 2011, during Idol’s tenth season on the air. That was also, coincidentally, the first season not to feature either Paula Abdul or Simon Cowell on the judges panel. Abdul, hailed by sources as a major supporter of queer contestants behind the scenes, parted ways with the program after Season Eight. Cowell left the following year to launch the U.S. spinoff of The X Factor, the British singing competition he created in 2004.

In a statement to Rolling Stone, Abdul says that she is “truly heartbroken that contestants felt an inability to be their fully authentic selves during a time meant for them to shine. Sexual orientation, gender identity, race, religion — none of that should matter when it comes to sheer talent.” She adds: “I will always remember the amazing contestants that it was a privilege to meet and mentor throughout my time with the show and am saddened that some left the show feeling that they had not been fully seen. My wish is that they all now are living in their truths and continue sharing their incredible gifts with the world.”

Abdul sued Nigel Lythgoe for sexual assault in December 2023, naming the production companies behind Idol and So You Think You Can Dance as other defendants. She settled with the production companies in April; her trial with Lythgoe, who has denied the claim, is set to begin next year.

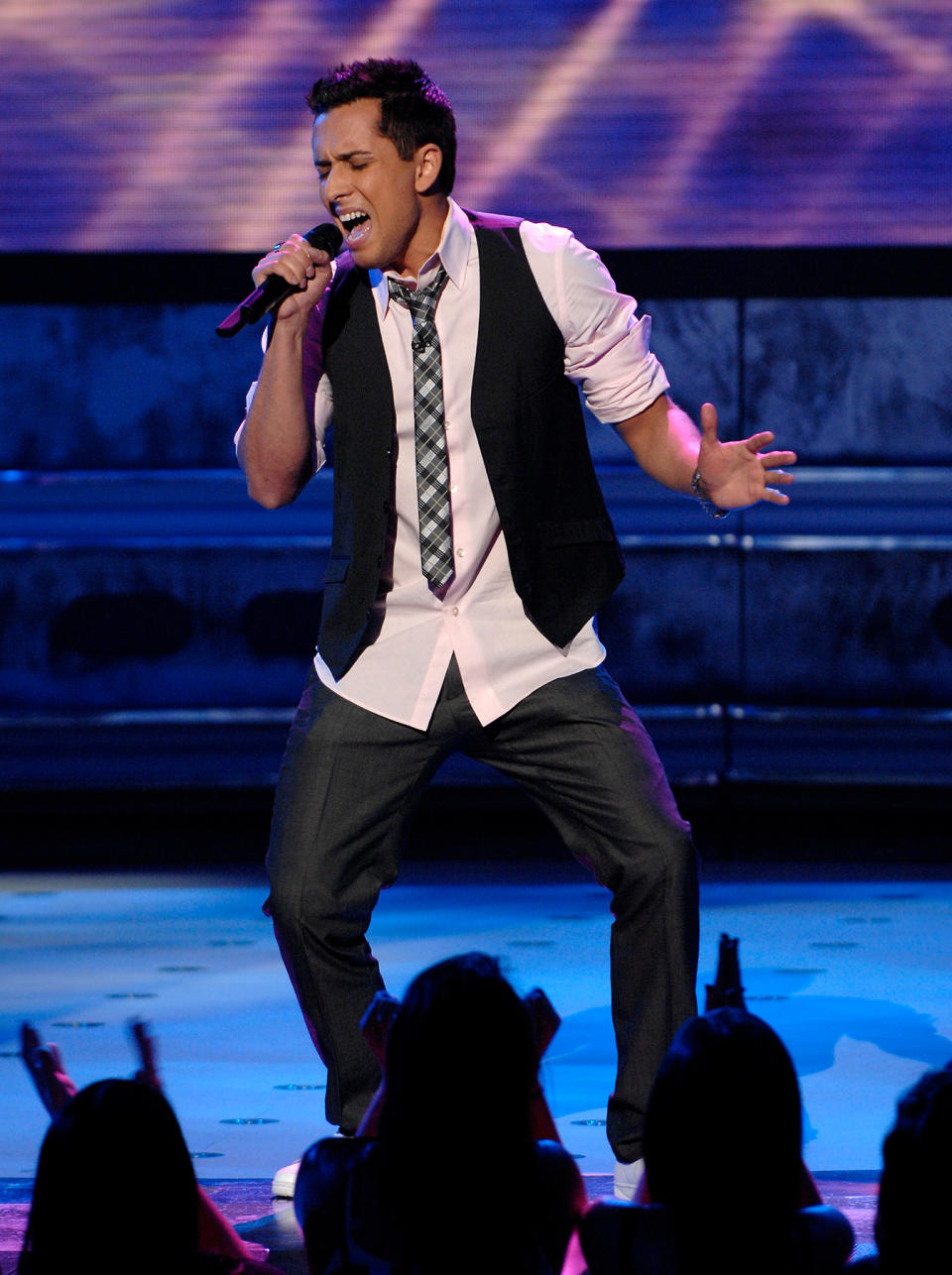

For all the troubles that some queer contestants say they had on the show, many argue that Idol’s missteps paled in comparison to how cruelly they were treated by the rest of the media, the music industry, and even America at large. Idol voters eliminated Season Seven’s David Hernandez the week after an Associated Press story revealed that he had previously worked as a dancer at a Arizona strip club that catered to a “mostly male” clientele. By that time, photos that allegedly showed Hernandez bartending at a gay nightclub had already been published on Vote for the Worst, although Hernandez says the pictures weren’t even of him. He says that Idol was already well aware of his work history by the time the reports surfaced, as he disclosed the information in the extensive questionnaire the show required contestants to complete; spanning over 100 pages in length, it also asked singers to name their past sexual and romantic partners.

Hernandez says Fox’s publicity team stood by his side as the reports continued to gain steam, but the flames of the media firestorm kept rising. “Perez Hilton would not stop talking about me on his blog,” he says. “TMZ followed me everywhere. Access Hollywood showed up to the former strip club that I used to work at, and they interviewed the manager.” Hernandez has bounced back since his short stint on Idol, spending the past 15 years touring and making music, but at the time of his audition he was homeless, giving up his apartment and his car for a shot at TV stardom. He took the news of being voted off the show hard, sobbing in his dressing room as security waited for him to gather his things. “Before that story broke, everything was great,” he says. “It’s not like my voice changed. It’s not like my style changed. Everything was still the same.”

The media persecution of queer Idol contestants was so de rigueur during the show’s imperial era that few even questioned it. Jim Verraros’ coming out in 2002 prompted a two-page spread in the Globe, a U.S. supermarket tabloid, asking: “Who’s Next?” Chatter surrounding Adam Lambert’s sexuality made the New York Times after photos circulated of the singer, eyes covered in makeup and glitter all over his face, locking lips with another man. Following the Season Two finale, Clay Aiken says that the first question that he was ever asked by a reporter was: “Are you gay?” He wouldn’t formally come out until a 2008 People magazine cover story coinciding with the birth of his son, and for years, he says, confirmation of his sexual orientation “was the only thing that anybody in the press wanted” from him. “I never did an interview where somebody was not trying to ask me if I was gay,” he says, later adding: “Everybody wanted to be the one who got it.”

Aiken says that speculation regarding his sexuality reached such a fever pitch that, for a time, he stopped leaving his house. Even then, there was no hiding from it: “If I heard anybody setting up a gay joke on a sitcom or a late-night show, I held my breath because I knew my name was coming. Eighty percent of the time I was right.” The topic was a frequent punchline of late-night host Jimmy Kimmel, who frequently booked Aiken to appear on his show, and comedian Kathy Griffin spent a full 15 minutes discussing Aiken’s sexuality in a 2005 stand-up special on Bravo. “I do find him to allegedly be the gayest man in the free world,” she said in the routine, calling him “Gayken” to hearty applause from the crowd. Even two years after he had actually come out, a Season Eight episode of Family Guy saw Stewie, during a parody of Family Feud, being asked to name a “popular fruit” and responding: “Clay Aiken.” “I laugh at them now,” he says of the jokes, noting that he calls Griffin a friend. “I find them hilarious now, but at the time, it hurt a lot.”

Even today, Aiken says the media frenzy of those days is difficult to distance himself from fully. His son, who is now 15, has recently begun watching South Park, and his friends will regularly text him because they saw a joke about his dad on an old episode. “Idol was the best bootcamp to train you and prepare you for what will come to you in the music industry,” Aiken says. “It did prepare us for everything. The only thing that did not prepare me for was: For the next five years, you are going to be the punchline for every gay joke.”

Having flown largely under the radar as a queer person during Idol, aside from the producer he says helpfully pulled him aside to show him how to de-swish his walk, Aiken maintains that the show was the “only safe space” that he had. “It probably would have been better if they had been rude and picked on me more for being gay on the show,” he says. “At least then I would have been prepared when I left.”

Best of Rolling Stone