Rema’s Culture Was Demonized. Now, He’s Doubling Down With New Video ‘Benin Boys’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

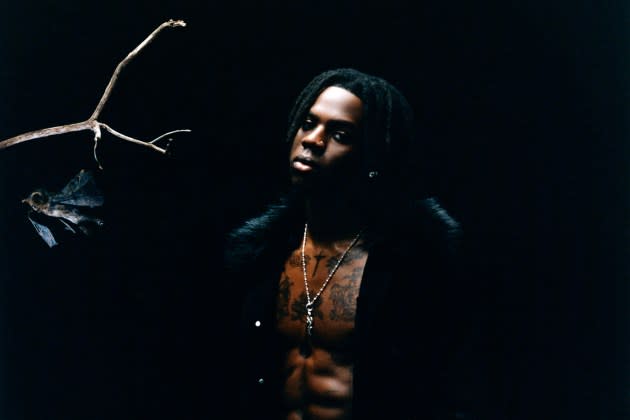

What do you do after you’ve made the first Afrobeats song to top U.S. radio, the first to earn more than a billion streams on Spotify as a track led by an African artist, and the first to cinch the MTV Video Music Awards’ Afrobeats honor (one they may have had to make because your hit was so massive)? If you’re Rema, you go home.

The 24-year-old took the world by storm in 2022 with his lover-boy anthem “Calm Down” and its remix with Selena Gomez, and has since stayed consistent with more quality music like “Charm,” “DND,” and a feature on Victony’s popular “Soweto” remix alongside Don Toliver and Tempoe. However, Rema tells Rolling Stone his sound is evolving and his latest single, “Benin Boys,” is a taste of it: a bold and brash declaration that no matter where life takes him, it’s his hometown in Southern Nigeria that got him there.

More from Rolling Stone

Rema was raised in Benin City and didn’t leave until 2018, when he moved to Lagos to work on his first and self-titled EP with one of the country’s premiere local labels, Mavin Records. When he headlined a sold-out show at London’s storied O2 Arena last November and evoked Benin traditions cloaked in rock-star drama, some fans from the show and on the web accused the imagery of being demonic. “Beware of the music you listen as a Christian” one clip of the concert on YouTube is titled. “It was sad. It was quite heartbreaking,” Rema says about the backlash.

He had made his first entrance on a massive prop of a Black horse, clothed in a long black cape and donning an elaborate mask above his mouth. That, he says, was an homage to the beloved wartime Queen Idia of the middle-aged Benin Kingdom. An important bronze bust of her head was taken by the British in 1897 and still remains in the British Museum among other key Benin Bronzes, though the Nigerian government has motioned for the return of those cultural relics confiscated in colonial pillaging. Later, Rema performed while riding a giant bat over the crowd, an animal common and revered in his city. He had previously shot down Illuminati accusations on the back of his bat symbolism. “Y’all would have so much clarity if you easily Google where I’m from,” he wrote on Instagram in October. “Jesus is king.”

So, he was especially disappointed when the accusations heightened after his concert. “Doing my first O2 show, I know that [our] arts are still in that same country. That was also me having a rebirth moment, being the first person to blow up this big from that same city. I can’t just go to Britain, a place that once upon a time invaded where I was from and just come simple,” he says. “Going on that stage, I went with the deepest intentions that people understood not just the music but the person behind the music. I was just surprised, and lost too, to see that people that I trust as fans just don’t understand. It’s like, ‘Would you ever love someone you don’t understand?’”

In turn, “Benin Boys” is a celebration of his hometown and heritage and features Shallipopi, an exciting and rising rapper from the same place. In the elaborate music video, the pair explore places sacred to Rema, they party, and they flex. The shoot was one of Rema’s first trips back home since his quick ascent. Everything filmed — from the scores of male dancers with shaved heads, the street signs showcased, and even the club scenes — means something special and particular to Benin City’s culture. “Every person who’s been in the club and seen a Benin boy do his thing [knows],” says Rema. “It’s like once they get successful, the first thing after family is to go is to buy a Mercedes-Benz GLE, go to the club, pour champagne on your wristwatch, get stacks, get girls, get a shit ton of homies.… We just have fun. The club is very important — it is part of the story,” he says with a laugh.

He notes that the music he has coming, though, is not all fun and games. You can still sense the seriousness in “Benin Boys.” “For the past years, I’ve been light and jovial. I’m quite intense this time,” Rema says. “One thing that you will hear in the future is just the rawness and realness — how raw Afrobeats has been before the whole globalization, but in a new way. With everything going viral and everything just spreading across the world, I feel like it has also affected the sound. We’re not just making what the people at home would enjoy. We’re also making what we hope the world would also enjoy. I got rid of that mentality getting in the studio, like, ‘I’ll start with what I love. The rest of the world can catch up.’”

Here, he breaks down his new music video, what it means to be from Benin City, and why our ideas of Afrobeats and Nigerian culture still need expanding.

I have a lot of questions about the imagery in the video. Let’s start with the song itself. How did “Benin Boys” come to be?

I hit Shallipopi up; I told him to pull up to my studio [in Lagos], and he did. We made three songs that day, but that was the first one we made. We always knew coming together, when we’re cooking up something, it has to be something that expresses where we are from. We’re from different hoods, so he would definitely be the perfect person to express his hood, me express my hood, and then in combination, just express Southside, Edo State in general. Edo is the state, Benin is the city. Beni is the culture.

So tell me about the difference between the two neighborhoods that you and Shallipopi are from.

Both rough, but mine is less rough. Shallipopi’s hood is very, very rough. It’s a lot of … we call them “agbero,” but it means thugs. It’s just filled with thugs. My area got a university, but it’s still mad rough. Lots of sports too, in that area. Lots of churches. But his end is lots of churches, lots of thugs, lots of killings, lots of madness going on on that side. Even when I was in the city, I rarely went because the hood was mad crazy.

Did y’all ever cross paths in Edo State at all?

Never. One of the major reasons why I usually [went] to Shallipopi’s hood is for two years I was constantly going to a particular studio. So I‘d usually go there, but we never crossed paths.

Speaking of churches, one of the locations in the video is a church. Is that a significant one or just a representation of how many are around?

It’s just an expression of how easy it is to know you are in Benin — one of the things that stands out is lots of churches, lots of bars, lots of clubs. But, yeah, the churches overpower every other building.

Another thing that I noticed in the video were some street signs. It sounds like you specifically shout out a street called Sapele in the song. Tell me about those locations.

Sapele is Shallipopi’s hood. Ek Enwan is my hood. I recently went back to Benin after five years, because I’ve been on a global run. I am grateful to God that I blew up really quick. I’ve had my family moved a lot of times. We traveled together, all of that. But I went back, and, yeah, it’s looking good. It’s developed, it’s beautiful. It was very nostalgic. I went back majorly for this video and then I just tapped in with everyone that needed me to tap in with them.

I saw a video of you on TikTok after I had seen the video, and it seems like the green building in the music video with all the kids’ cartoons painted on it is your old school.

Mm-hmm. Just 10 minutes away from my house. I would still always go very late. It’s a nursery, primary, and secondary school [called] Ighile Group of Schools.

Is it still operational? Do students still learn there?

Yeah, I spoke to the school. We’re having great talks about switching it up, taking the school to the next level.

By that, do you mean helping them develop, modernize, stuff like that? Have more resources?

Definitely. Because I feel like things didn’t really develop since I left that school, and I feel like it’s quite important to give back.

On to some of the other symbolism in the video.… All of the dancers are men, and they all have shaved heads. They have on these red half-sweaters. Tell me about that.

So let’s start off with the shaved heads. In Benin City, when the king dies and the prince is about to take over, all boys in Benin shave their heads. I think the new Oba, the new king, subsided a little bit. He said every first male born from every family should go bald. So if you’ve had dreads for seven years, you cut off your dreads or you are gone. It’s quite a strict law. It signifies a fresh king coming to the throne.

So during your lifetime, have you ever had to shave your head?

I think once. Just one Oba died when I was in Benin. I went to school bald. [They were] smacking my head.

OK, so that’s the shaved head. The dancers in the video also have bats drawn over their eyebrows. I know that the bat has been a symbol that you’ve evoked for a long time, but tell me about it.

So in Benin City, every evening, there’s always bats in the sky, just flying to their cave. Early in the morning, around 5 a.m., they all fly to the Oba palace, the king’s palace, which is quite spiritual. Throughout the whole day they just circle around the Oba palace. There’s a very big tree [there] that they’d usually just be [at]. It’s something that every person from Benin knows. In other cities, it is quite scary for them to just see bats in the sky. It’s quite odd for them, but, yeah, it is normal in Benin. Everybody sees bats. Bats fly into our window when we’re sleeping at night, and we’re not worried. We love bats.

And the sweaters. Do the red sweaters symbolize anything or the outfits in general?

The outfits don’t really signify anything. It’s just the color. The red signifies the culture. We’re huge on red and white — black when it comes to some very deep situation or traditional situations, but usually red.

It looks like many Benin Bronzes are evoked in the video. They’re well known as being stolen from your people by the British. Are the ones in the video real?

They’re real. Those are ones that are still in Benin. The Benin culture is known for sculpting and bronze arts. They have streets dedicated to bronze arts. It’s been for some time, since the beginning of the Benin empire. It’s a way to keep memories of people, of kings, of heroes, of how the culture progressed. It is still our signature art.

If you [look at] museums in the U.K., Germany, and a few other [places] around the world, our bronze arts have spread because we got invaded. The Benin empire got invaded by Britain, and we got a lot of our very, very, very, very iconic bronze art stolen, which was very sad. It was a massacre. And especially the Queen Idia head because she fought against oppression. She’s like a war queen; her face is … it’s like the face of Benin. The bronze art of her is a symbol of Benin. We’re huge on bronze art. It’s everywhere around me.

There’s still been a lot of iconic pieces made, [they’re] even in Benin’s museum, there’s just so much history tied to the ones that were stolen by Britain, sold to Germany, just being passed around. I recently spoke to the governor about it as well, and I heard they’re working on getting these treasures of ours returned. It’s quite difficult because [the Europeans have] been very stuck up to even resell or anything. It’s just lending; that’s what they’re leaning towards. But we’re not feeling that. It’s ours.

It seemed like some of the symbols we’re discussing, like the bat and bronzes, were evoked at your O2 show and there was some backlash. There were people claiming it looked demonic. How was it hearing those criticisms after doing this monumental performance?

I’ve done a lot of interviews. I’ve done a lot of expressions. I put signs out there. Firstly, it was quite sad that I felt like all of this work that I put in to help the fans be aware [was] quite ignored. [It] felt like they cared so much about the music, posting about it, dancing and all of that, the good side of it, but not even trying to care a little bit more to understand the person where this music came from.

Secondly, I was just quite sad to see people who celebrate Halloween and things that were just made up and actually demonic call my own culture demonic. It’s quite weird. It’s kind of bizarre because my expression is real. What was beautiful was being on that horse with that mask of Queen Idia — I re-created my own version of Queen Idia’s mask.… Everybody who knows Benin culture understands what I did. That was women’s empowerment literally coming out on that stage. It is quite rare to see a lot of people do that right now, especially in the Afrobeats space.

I feel like my parents and my background have educated me properly to send my message, to give people awareness. And just felt like I had a lot of fans that didn’t care, that didn’t understand me. There were quite a good number of Black people there, but just seeing Black people being ignorant and thinking just vibing to Afrobeats is being part of the culture. No. Or [thinking] vibing with the most popular traditions is being tapped in. No. They’re not even aware there’s over 256 small cultures in the same Nigeria with 36 states, you know? They’re just very vast with the “Oh, if you’re not Igbo, Yoruba, Hausa….” Like, that’s the basics.

Then, they go ahead to label things they do not know about; things they do not understand. It’s very sad to watch, and sad to see my brothers and sisters in the diaspora [not] actually taking time to learn where they’re from. Saying you’re Nigerian and you don’t even understand a few basic things. Even saying, “Oh, I know Yoruba. Oh, I’m just Yoruba.” Cool. But the Benin culture is tied to the Yoruba culture. I can bet a lot of young people don’t even know that. It was quite sad to see a lot of young people not even aware of themselves.

I will say, just being Sierra Leonean-American myself, I think you’re right; I think that there’s sometimes a lack of curiosity. I think it’s also because, while you want to understand your African-ness, we’re just kind of getting to a place where there’s wide social interest in that alongside the growth of Afrobeats. Before that was cool, you were encouraged to suppress your African-ness. Now that it’s cool, you may have a lot of catching up to do. Then, you’re also still balancing your Black American culture or your Black British culture at the same time. But I think I really agree with you that there was a lack of curiosity. I think in all relationships, including fan-artist, it’s important to not point fingers and declare, “This is this,” but to instead ask, “Why is this this way?”

Yeah. They paid to enjoy their favorite artists and their best songs, to see this person behind the song … but it’s like, you wouldn’t do that for someone you don’t care about, right? So wouldn’t you like to know who this person is, what’s going on with this person, the mind that this music can come up from? This person created the biggest African song. I just expect fans to care more.

Especially when you won the first Afrobeats MTV Video Music Award, you embraced the term “Afrobeats” when a lot of other artists have debated or rejected it. It is an umbrella term, especially in the West, and very different approaches get lumped under it, but I think that it is also significant that you embrace it anyway. Tell me about making that choice and how you feel about Afrobeats as an idea now.

I feel like I don’t want to go too deep in this, but I’m going to say I understand. It’s quite an honor to follow such great paths that Fela Kuti created [with Afrobeat, his fusion of West African and American musical styles that predates Afrobeats, which is also cross-cultural]. But I feel like at some point, some people want to look back and be like, “What will I be remembered for? Will I be remembered as someone that walked in another man’s shoes? Or do I want to create something for myself?” Everybody wants to be their own Fela at some point in their career.

For some people, it might just be sound. They’re like, “Yeah, I’m doing Afrobeats, but I’m just excited to do everything, and I don’t want to be lumped in that one category.” Most of these talks really started when everything started getting really globalized. Let me look back and say the likes of 2Face or D’Banj, them OGs back then, they were mad experimental with different sounds, but they still succumbed to the umbrella term as the globalization of Afrobeats started.

I’ve been able to view good heights by God’s grace. I would also say when I was making “Calm Down,” I never thought the rest of the world would vibe to that. And I won’t call it pressure, but it seeing everyone having a huge song and gaining this big success and a billion streams — there’s no artist that doesn’t want that for themselves. It’s quite OK for everyone to lean into whatever sound they want to, but I just feel like we should never forget how it has always been. I’m doing really great with amapiano. I feel like Afrobeats was once in that space, where our beats were crazy and insane in every club across Africa at first, even before the rest of the world caught up.

But for me, I always talked about Afro-Rave [the genre he coined for his music] really because of how different my sound is, how energetic my sound is. But I would never shit on what started it. I would never look down on it. It has fed me, and it has fed my family. It has given me a chance to express myself. And if it goes to the length of dropping Afro-Rave to raise Afrobeats, I would do that gladly, because it took me this far.

Best of Rolling Stone