How the studio behind The Godfather and Chinatown can get its swagger back

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Francis Ford Coppola hadn’t expected Robert Evans to strike a particularly respectful tone at the screening. But even he hadn’t foreseen him turning up in a hospital bed.

It was 1971, and Coppola was showing an early cut of The Godfather for his bosses at Paramount – a group which included Evans, the studio’s eccentric head of production, who went on to preside over some of the greatest films Hollywood ever produced. Coppola, then 32, was in the process of finishing one of the first of them – and the 41-year-old Evans had fought him on just about every major creative decision he’d taken while making it.

First there was the casting. For the central role of Michael Corleone, Coppola wanted the relatively unknown Al Pacino; Evans had lobbied for an established star like Warren Beatty or Robert Redford. Then there was Marlon Brando. Evans called his delivery of the now-iconic “look how they massacred my boy” monologue “the most overacted, worst-played scene I’ve ever seen.”

Their latest battleground was the edit. Evans had injured his back a few days previously, but was so determined not to cede any ground that he had his butler wheel him to the studio in a motorised cot. He’d dressed for the occasion, too. In Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, critic Peter Biskind’s landmark account of 1970s Hollywood, he describes Evans’s outfit of “fine black silk pyjamas and black velvet slippers with gold foxes brocaded on the toes”.

Coppola would later recall hearing the motor whirring during the scenes Evans found boring, as he moved the reclining mechanism down to take a nap. Meanwhile, the screenwriter Robert Towne, who had helped shape a crucial late scene between Brando and Pacino, watched the bizarre pantomime in dismay. “If this man is running a studio,” Biskind describes him thinking, “this industry must be in big trouble.”

Except it wasn’t: quite the opposite. In fact, it’s the Paramount of today – the only independent studio from Hollywood’s golden age not owned by a mega conglomerate – that is now in beleaguered limbo, after its owner Shari Redstone scuttled a months-in-the-making $2.3 billion merger with Skydance Media, right at the moment a deal was expected to be signed. The studio, which made its name on large-scale theatrical releases and cable and network television – but has found its lunch pinched by the streaming era – could sorely do with some of Evans’s maverick magic.

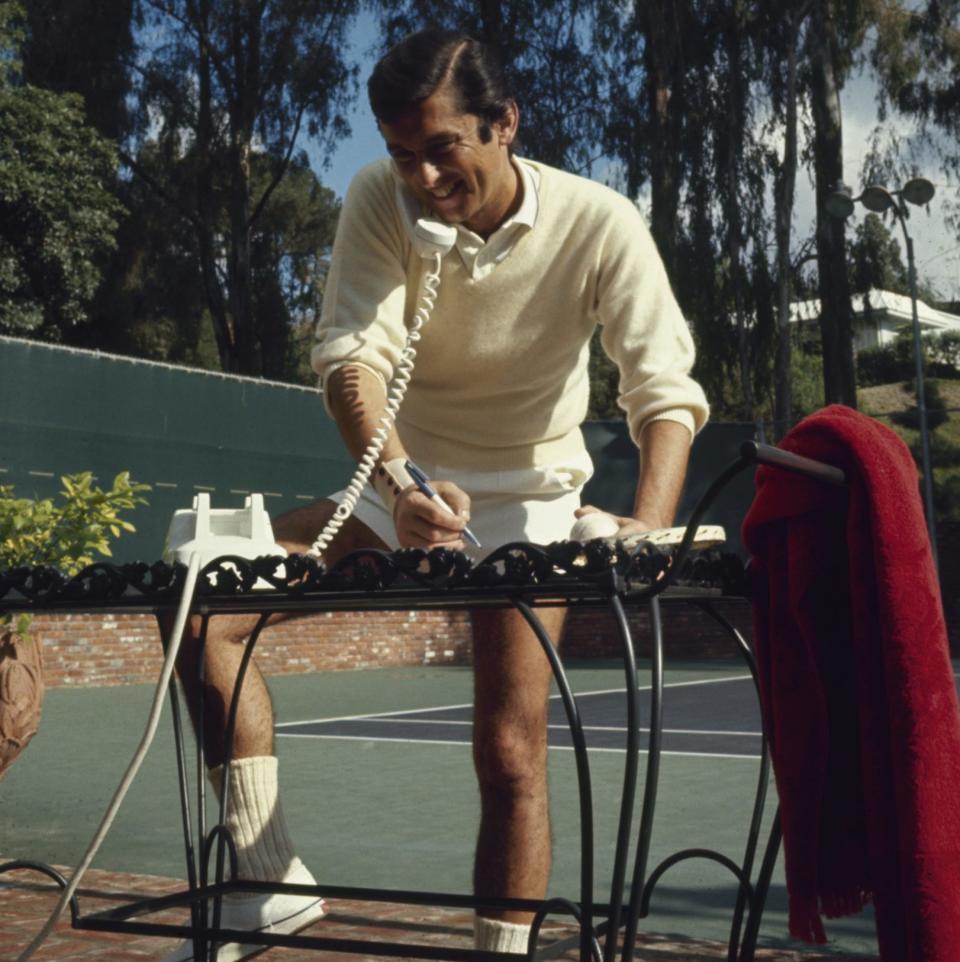

Yes, Evans may have been a walking Hollywood cliché, with a ludicrous grace-and-favour 16-room house in Beverly Hills, an Olympian sex life, a mania for parties (the starrier the better), and the sort of cocaine intake that could give a rhinoceros heart failure. Yes, he married seven times – once to Ali McGraw, one of the hottest young actresses around, in between working with her on Goodbye Columbus and Love Story. And yes, he once got caught up in a contract killing scandal after one of his producing partners was murdered by a drug dealer. (At the subsequent trial, the dealer – an ex-girlfriend – insisted Evans hadn’t been involved.)

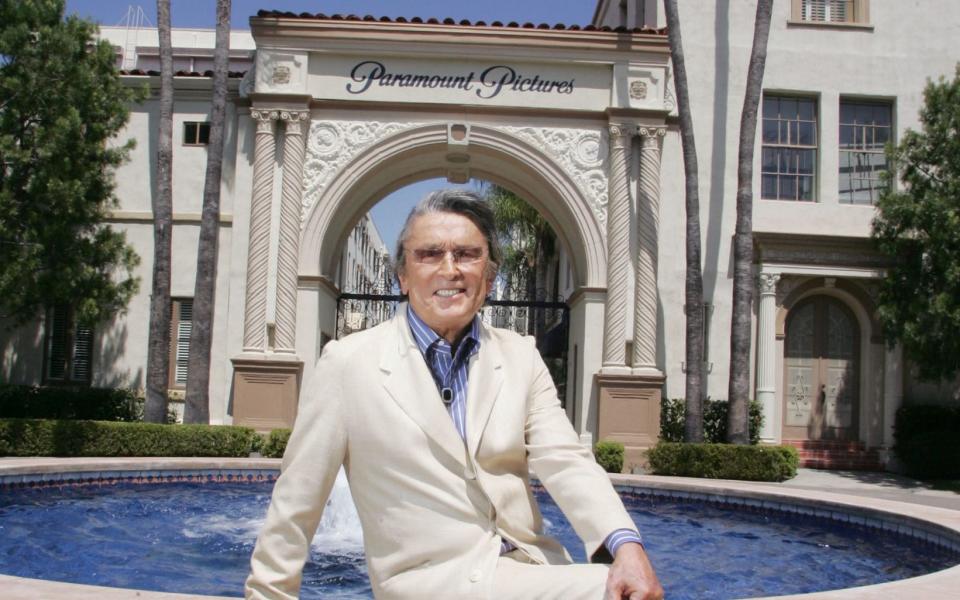

But behind the teak complexion and Persil teeth lay enough wit and nerve to heave Paramount out of a historical slump and into a mini-golden age. During his eight-year tenure as head of production, he oversaw the making of the following films: The Godfather parts I and II, Rosemary’s Baby, The Italian Job, Paper Moon, A New Leaf, The Conversation, The Odd Couple, Harold and Maude, True Grit, Serpico, The Great Gatsby. Oh, and Chinatown, written by one Robert Towne – who had evidently got over his misgivings about Evans when he came to him to strike a script deal, not long after the night of the black silk pyjamas. After the release of Chinatown, Evans left Paramount to work independently, but was unable to replicate that extraordinary streak.

Incredibly, he had no prior experience as a producer, unless you count pretending to be one. A former child voice actor, he came to Hollywood in the 1950s to be in the movies – and his first named role, in Man of a Thousand Faces, was the legendary MGM production head Irving Thalberg.

Legend has it that he was cast after Thalberg’s ex-wife, Norma Shearer, spotted him lounging by the pool of the Beverly Hilton. And the story rings true, since Evans, 36 at the time, was popular with wives. In Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Biskind describes how the French spouse of the studio’s then-owner, Charles Bluhdorn, sweet-talked her husband into hiring him. “He’s gorgeous,” she reportedly told him. “We’ve got to get a good-looking guy, real sexy, to run the company.”

So he did. The appointment, Biskind notes, was widely regarded as “bizarre, even by Hollywood standards.” But there was a mad alchemy to it that worked. Evans had a gift for keeping the talent sweet, and a habit of betting big on talented young directors who had just weathered a flop. And while he often fought with his creatives, he would just as often back them to the hilt. On Paper Moon, he allowed director Peter Bogdanovich to shoot in black and white without running the decision past another person in the studio, with the exception of his number two (and future Variety editor) Peter Bart.

Evans’s tenure may have been chaotic, but it restored a sense of purpose at Paramount that had been lost when the studio’s cinema-operating and film-making arms were broken up after a high-profile court case in the late 1940s. When it was founded in 1912 as the Famous Players Film Company, the studio had quickly made its trademark old-world sophistication and glamour, with help from suave emigré directors like Josef von Sternberg and Ernst Lubitsch. Almost single-handedly, Evans burnished that lustre again.

That ambition and cosmopolitanism bears little relation to Paramount in the 21st century, whose driving creative philosophy has essentially been “throw a lot of money at Tom Cruise”. To be clear, there are many worse creative philosophies than that – but it only works when your customers are throwing money back. And as the middling box office take for last year’s Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One showed, even having the planet’s biggest movie star drive a motorcycle off a cliff isn’t enough to tide you through a rough patch. So any sale – if and when one finally occurs – will likely be followed by a floor-to-ceiling artistic rethink.

In truth, such a revamp couldn’t come soon enough. Paramount has been suffering from creative drift ever since 2009, when they lost Marvel Entertainment to Disney. In 2012, as the latter studio flew high with Avengers: Assemble – and got into position as the dominant force in Hollywood for the decade ahead – Paramount ended up sitting out the summer entirely, bumping their two biggest titles, GI Joe: Retaliation and World War Z, to the following year.

Both the films themselves (which were dreadful) and the act of not releasing them smacked of anxious management think: a mindset the Evans-era Paramount wouldn’t have recognised. Yet for now – and given the current air of uncertainty, presumably also for the foreseeable future – the ethos appears to have stuck. The studio’s three current CEOs are the sort of dyed-in-the-wool executives it’s impossible to imagine turning up at work in deluxe nightwear or giving evidence at a murder trial. One, Brian Robbins, was a filmmaker at one point – though his directing credits include eight-time Golden Raspberry nominee Norbit.

So the vacancy for this generation’s Robert Evans remains open – though it’s admittedly impossible to anticipate who that sort of figure might be (and whether today’s cautious HR execs would even allow him into the cockpit).

Yet the fact remains that no-one anticipated who Robert Evans’s generation’s Robert Evans would be either. But how fortunate that Hollywood back then was bold – and mad – enough to imagine Robert Evans might be it.