The wild career of Cold Chisel, the Aussie hellraisers who should have been as big as AC/DC

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

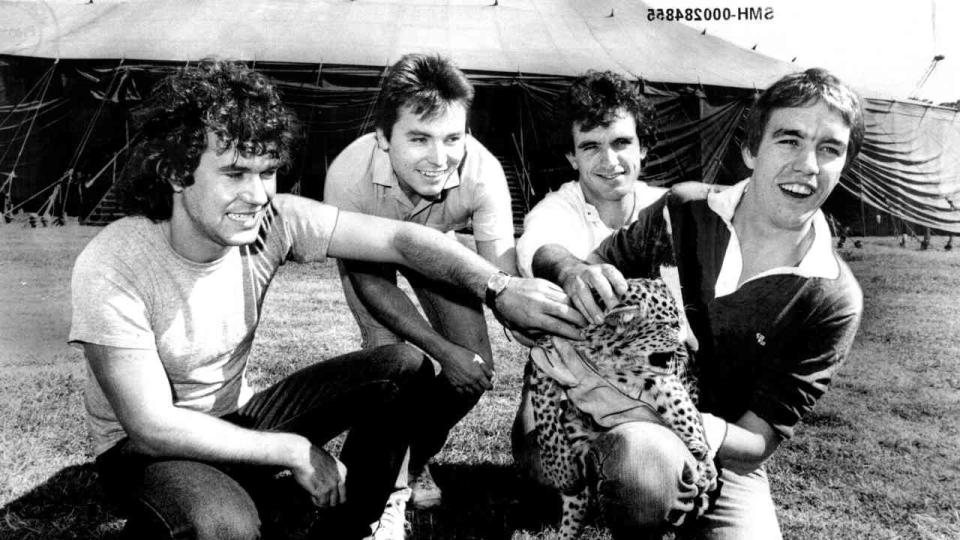

Cold Chisel may not have the international profile of countrymen AC/DC, but they’re bona fide Australian national treasures – albeit ones whose combustible career is littered with onstage and offstage brawls, bust-ups and splits. But when Classic Rock sat down with the recently reunited band in 2012, they were unrepentant about the highs and lows of their rollercoaster career.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing. “We should’ve ‘done an AC/DC’ and got the hell out of Australia,” Cold Chisel guitarist Ian Moss says, “but of course you can’t turn back the clock.”

Led by the intimidating Jimmy Barnes, Cold Chisel graduated from the bare-knuckle cauldrons of the Australian pub-rock circuit to become national heroes. Glaswegian-born Barnes, who briefly replaced Bon Scott in the band Fraternity, was their talisman. With vodka bottle fixed firmly in hand, he crouched low onstage – either to maximize vocal power or prevent himself from keeling over – a steely gaze fixing the front rows with a warning of ‘look away at your peril’.

“You knew where you stood with Aussie audiences,” reflects Barnes now. “They could be fantastically appreciative if they liked you, or otherwise they’d throw bottles, ignore you completely and just walk out. So the trick was to play like demons and get two or three of them on your side by whatever means necessary. As we improved so the crowds grew and slowly, very slowly, things evolved.”

Countrymen Rose Tattoo and The Angels have related many horror tales of this tough environment. “There was alcohol, plenty of fighting… sometimes guns. And that was just the women,” grins songwriter/keyboard player Don Walker.

Cold Chisel enjoyed lots of partying, even more drugs and girls a-plenty, Barnes’ showmanship their focal point. “Playing as often as we did, there were nights when I just couldn’t deliver quality-wise, so I’d smash the place up and everyone walked away saying: ‘What a fantastic show’, but it was just smoke and mirrors. All anybody remembered was the singer leaping from the PA, shoving the microphone stand through the roof, ripping down the lights or fighting with the bouncers.”

Emerging from this unlikely training ground, an earthy fusion rock, blues and soul that’s most often termed ‘pub rock’ transformed Cold Chisel into bona fide Australian A-List celebs. However, their inability to repeat it in the Northern Hemisphere would eventually inspire an ugly, frustrated self-implosion.

Cold Chisel were formed in September 1973 by Moss, Walker, drummer Steve Prestwich and bassist Les Kaczmarek (whose replacement Phil Small completed the definitive line-up 18 months later) as what amounted to a heavy rock covers band, playing material by Deep Purple, Led Zeppelin, Hendrix and Free. The son of a former British boxing champion whose family relocated to Australia when he was four, 16-year-old Barnes joined later that same year.

“The others were very different to me,” remembers Barnes. “I was from Port Elizabeth, a town that was built for immigrants. My school-friends were working class Brits; the Irish and Scots. There were lots of drinking and street gangs. The other guys were quieter and fairly well educated.”

Curiously, Barnes clashed more with another ex-pat – Liverpool-born Steve Prestwich – than any of the Aussies. “That was a bit of a problem for Steve, who couldn’t fight his way out of a wet paper bag,” laughs Ian Moss.

Barnes elaborates: “We both came from working class background but unlike like me Steve was a gentle soul. We’d get wild and take the piss out of everyone. Sometimes we’d become really drunk and throw punches at one another, but beneath it all Steve and I were best mates. Punch one of the others and they’d take it personally, but it was just something that Steve and I did. Brothers fight but they also forgive.”

The hot-headed Barnes quit Cold Chisel many times, but the sheer monstrousness of his voice ensured that the wayward singer was always forgiven, no matter how large the indiscretion.

“Ian [Moss] took over the vocals,” says Phil Small, “but then Jimmy would sniff around to come back and he’d be welcomed with open arms.”

A ludicrous example of this took place in 1977 when Barnes decided to join his brother, John (nicknamed Swanee), in the rival group Feather. However, a farewell Cold Chisel performance was so well received that Barnes changed his mind and the rest of the band accepted his U-turn.

“I’ve always been impatient, impulsive and easily swayed,” he comments. “Swanee often talked me into storming out and playing with him, but then I’d go and see Cold Chisel and realise: ‘Shit, this is my spiritual home’. So back I’d go.”

Jimmy’s sibling was also responsible for persuading Barnes join Fraternity as replacement for the AC/DC-bound Bon Scott. This arrangement lasted for just six months but bassist Bruce Howe took the fledgling singer under his wing – “he taught me more about vibrato and pitch, the stuff he’d coached Bon with” – and Barnes returned to Cold Chisel an improved performer.

Before signing to Warner Bros in late 1977 Cold Chisel had gigged solidly for your years. “It felt a bit like winning over each fan individually,” Barnes now half-jokes. “We’d play anywhere and everywhere we could, sometimes we did three shows in one day.”

The Warner Bros contract was for just three albums instead of the usual five, the label cautious of teasing a hit song from the pandemonium. However, despite murky sonics disguising their live firepower, the first single from 1978’s Cold Chisel put the band on the map instantly. Banned for blatant references to drugs and sex (‘Their legs were often open/But their minds were always closed’), Khe Sanh told of the reintegration difficulties of a homecoming Vietnam soldier. Short-term it confirmed the band’s reputation as mavericks but despite its tricky subject matter Khe Sanh seeped into Australian culture, even becoming a victory anthem for the nation’s cricket team.

“The best thing you can do for a rock’n’roll band is to ban them,” points out Phil Small. “That song is now embedded in Australian folklore.”

With stardom beckoning, Barnes’ hell-raising antics snowballed. As the singer’s alcohol intake reached two bottles of vodka a day, Phil Small confirms that his bandmates began to secretly fear that each show could be the last. “It was definitely there in the back of all our minds at certain times,” he says. “Sometimes the alcohol affected Jim’s voice and he was completely out of his tree.”

“I was very concerned about Phil, too,” deadpans Barnes, before issuing the punchline: “I was worried he’d bore himself to death.” As his laughter subsides Jimmy volunteers more earnestly: “I knew they were anxious about me at times. On other occasions they split their sides laughing – both with me and at me, but that’s brothers for you.”

Although drugs were only truly dangerous later on when he could afford them, they were an issue. “Dealers would say: ‘You don’t need any more, mate’. And those guys were totally unscrupulous,” Barnes once said.

A welcome stabilising effect arrived in the shape of Barnes’ future wife in November 1979. “Jane turned Jimmy’s life around,” Phil Small theorises. “Without her he’d quite possibly be dead.”

That same year’s Breakfast At Sweethearts album offered significant creative progress but once again the band hated the production, this time from Richard Batchens. Barnes once said the LP “stunk”, adding: “And you can spell that f-u-c-k-e-d”, which considering the excellence of material such as Goodbye (Astrid Goodbye) and Shipping Steel is telling. Despite such reservations it became the top selling Australian album of 1979.

Sonically speaking, Cold Chisel finally made a record to be proud of at the third attempt. Released in the summer of 1980, East is their catalogue’s colossus, the success of songs such as Choirgirl, My Baby and Cheap Wine helping it to sell five times platinum in Oz.

East was such a huge record for Cold Chisel that in early 1981 the band won all seven major categories at the prestigious Countdown/TV Week Awards. However on the night they refused to accept their trophies, electing to smash up both the stage set and their instruments to end a version of My Turn To Cry. Viewable on YouTube, the footage now seems tame but it provoked outrage at the time.

“We were protesting the fact that nobody wants to know you till you’re No.1,” explains Small, though Barnes adds: “It was also about being forced to mime. I had to fight tooth and nail to sing live, but they wouldn’t allow the band the same respect. East had become so big, we just wanted to have fun and shove it up them. When it was over we ran out the back door laughing like schoolboys.”

With Australia conquered, Cold Chisel began to look further afield. However, overseas success was to prove more elusive. A 1981 tour of North America offered five weeks of differing fortunes as the band fared well supporting Joe Walsh, Heart and Cheap Trick but were booed offstage while opening for Ted Nugent. “Nugent likes to kill animals with his bare hands to see the light fading from their eyes, and now he talks about politics?” Barnes bristles angrily. “We were a serious band, but Nugent would swing from one PA stack to another in a loincloth… we didn’t care what his audience thought about us. I’d like to have hunted him with a knife!”

As others had already discovered, carving an in-road to the US could take as long as three or four years, often at the cost of domestic status. After working relentlessly for eight years in Australia, Cold Chisel simply couldn’t spare the time.

“By the time that taking a real shot at America became a realistic option we were too dysfunctional internally,” admits Don Walker.

“Besides which, we were uncomfortable there,” adds Barnes, who responded with a song called You Got Nothing I Want on the next record, Circus Animals. “We’re blues fans. We love America’s real rock’n’roll bands but America then was all about The Eagles. With hindsight, it was foolish to have overlooked such a huge market but the place disillusioned us. We didn’t want to go back there.”

Circus Animals once again topped the charts at home but frustration boiled over on a trip to Germany in 1983. During a show Don Walker tipped up his keys and exited the stage, and after what Barnes terms a “blow-up” between Walker and Prestwich the band reluctantly fired their drummer.

“By and large I prefer to play a keyboard than throw it around,” recalls Walker of his onstage meltdown in a voice dripping with sarcasm. “Why did I do it? We were on a major international tour and the band was playing like crap, which was a new and very frustrating experience for us.”

Unsurprisingly, a break-up was imminent. Struggling to make ends meet having become a father, the now married Barnes requested a sizeable financial advance from the group’s management, declined on the grounds that it would also be payable to the other members. During a stormy meeting the singer tendered his resignation.

“We’ve never settled who quit the band first,” reckons Walker. “I think it was me.”

“Actually, I was the first to say that I was leaving,” Jimmy insists. “We were working hard and not making money. Bad decisions – investments – were being made on our behalf; it felt like we were knocking our heads against the wall. It was better to go out on a high and than a slump.”

Although Steve Prestwich was invited to return, sadness, rancour and uncertainty hung heavily in the air during a farewell tour. “We were determined to enjoy our time onstage, but there was an enormous sense relief that we might be free of all this,” Walker remembers. Ian Moss agrees: “The atmosphere had become completely unbearable.”

With some band members unable to share oxygen and Prestwich gone, the piecing together of a final studio record with multiple producers was a nightmare. Somewhat accurately Barnes once stated that Twentieth Century sounded “like a dying band”.

“I was so terrified by the prospect of moving on that the band broke up in December ’83, and by the following February I was back out on the road alone,” admits Barnes. “I didn’t want time for people to compare me to Cold Chisel. Luckily, it worked.”

Beginning with the hastily recorded Bodyswerve, Barnes notched eight consecutive chart-topping albums in Australia. In 1987 he tried again to woo the US market. A third solo release was largely co-written by Jonathan Cain and featured Cain’s Journey bandmates Neal Schon and Randy Jackson among a vast and dazzling supporting cast. However, despite being picked up by Geffen Records and becoming an AOR cult favourite, Freight Train Heart failed to dent Billboard’s Hot 100.

Cold Chisel offered immense resistance to reunion proposals. Multiple offers, including a cool $5 million to perform single shows in each of the major Australian state capitals, were declined, and it wasn’t until 1993 when Don Walker wrote Stone Cold for Barnes’ solo album Heat that the ice began to thaw. “It took a while for curiosity to overcome reluctance,” Walker muses.

After reconvening in 1995, a second reunion three years later also resulted in a studio album called The Last Wave Of Summer. Tension was still rife, however, and attempting to detail the song selection process Don Walker once stated that the sessions were riven with “psychological manipulation, sullen looks, petulance, tantrums, insane rages both faked and real, sexual coquettishness and pathological violence – sometimes the last two together”. Keen to cast things more harmoniously, he now simply sighs: “I must do too many interviews, it really wasn’t that bad.”

Any lingering disputes were ironed out by a series of shows in 2003/’04 and a year later the band played again to benefit relatives of the thousands that had perished in the Boxing Day tsunami.

Three years ago they attracted a career record 50,000 fans in Sydney, but it was the sudden death of Steve Prestwich in January 2011 that forced Cold Chisel to evaluate what they had. As the band worked amid top secrecy demoing material for a Kevin Shirley-produced new album that would later be christened No Plan, the drummer had complained of headaches and memory loss.

“Steve had had a tumour twenty years earlier but didn’t know he was ill until he started recognizing the symptoms [of brain cancer],” Barnes sighs. “His passing made us all realise the stupidity of allowing pride or bickering to prevent us from playing together.”

Lyrical observations such as ‘The old anger has given way/To clear eyes and open hands’ suggest that Cold Chisel have reached maturity with a first new album in 14 years, though thankfully without sacrificing their musical edge. “There’s a lot to be said for growing older and wiser,” says Phil Small. “Experience teaches us to understand strengths and weakness in others, and to accommodate them.”

Barnes admits to having calmed down significantly. “I’m not a vicar but I’m nowhere near as self-destructive as I once was,” he reveals. “We still have the same old intensity and aggression. But because it doesn’t have to be delivered eight times a week we can channel it so much better.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 173