BMX Star Nigel Sylvester Is Gonna Keep Going Bigger

The jump looks spontaneous, improvisational, like a wild existential leap, but in fact the trick was meticulously plotted and choreographed. Nigel Sylvester had scouted and schemed for weeks during the spring of 2013, riding the subway through Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens, finally settling on the 145th Street Station, far uptown on the west side of Manhattan, at two in the morning, when no one was around to tell him no.

In the published photo of the jump, the one that went viral on Instagram, Nigel looks immaculate, as if he were making a BMX tutorial. In flight over live subway tracks, he’s

wearing a white knit cap and a red hoodie that sails out behind him like the tail of a subterranean bird of prey. His posture is relaxed, balanced, and centered aboard his bicycle. You can’t tell that he doesn’t stick the landing-that, without brakes (in New York freestyle BMX, many riders forego brakes), Nigel’s momentum will drive him over the edge of the far platform and spill him hard onto the adjacent set of subway tracks.

A post shared by nigelsylvester (@nigelsylvester) on May 14, 2013 at 9:58am PDT

Nigel doesn’t have to suffer like this. He needn’t dodge the rats in a subway station at 2 a.m., nor obsessively hunt for the next ramp or rail on which to stage a trick. Nigel Sylvester is a brand name, arguably the best-known BMX rider in the world. He’s a crossover figure, a friend of Jay-Z and Pharrell Williams. His photo has appeared on billboards for his corporate sponsor, Nike, and in 2014 he would pose naked for ESPN The Magazine’s body issue.

But here he is, at the 145th Street subway station, his brain buzzing, thinking about a half-dozen things at once. How he’s going to cover the 13-foot distance of the jump. How Timothy McGurr, the photographer, will shoot the scene. How Nigel’s clothes look, the way his shoes and jeans align with his bike. He’s got bigger worries too, such as, what happens if a transit cop comes down here on patrol?

Nigel doesn’t have to fret about the law. He’s attained enough stature to operate on sanctioned channels. But in freestyle street BMX, in the same way you don’t ride with brakes, you don’t ask permission. You trespass first and ask forgiveness later.

Now he sets up for the jump. McGurr climbs down to the tracks so he can get a better angle. The photographer nods to his assistant. She signals to Nigel, waiting 90 feet up the platform. She punches her stopwatch and they’re rolling.

It’s dead quiet in the station. Yellow-painted steel beams cross overhead, the paint flaking in spots. The tracks vanish into the tunnel darkness. The whir of Nigel’s tires on the cement, the chuff of his breath, only seem to deepen the enveloping silence.

Nigel powers down the platform, gathering velocity. Now he hooks hard to the left, pulling up on the handlebar and throwing back his shoulders on the takeoff. The camera flashes as it captures the image: a slender young black man, in the belly of the urban beast, airborne on a bicycle, at the defiant apex of his leap.

Four years later, August 2017. I meet Nigel at Coleman skate park on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, on the edge of Chinatown, in the shadow of the massive gray pillars of the Manhattan Bridge. If he had more time, more energy, he would hit the streets on this Sunday morning, but Nigel is tired. He was up late last night editing GO Dubai, the latest in his series of BMX-themed travel videos, which are widely available on YouTube and other online platforms.

The earlier episodes in the series had been set in New York City, Los Angeles, and Tokyo. Shot with a GoPro, from a first-person perspective, the videos show Nigel romping through the cities on his BMX bike. He careens in and out of buildings, offices, and restaurants, soars over and between parked trucks and cars, drills into beating waves of traffic, and tight-ropes rails and edges, slaloming through each metropolis in a manner that seems equal parts Mad Max and playful dance. You see the jumps, spins, and grinds as he experiences them. Designed to appeal to a crossover audience, the GO series has drawn nearly 17 million page views on YouTube.

Nigel aims even higher in his current project. “I’m always thinking how I can surpass what I’ve done before,” he says. “Pharrell, Jay-Z, aren’t content just making records. They move on to scoring films and starting and running businesses. They can’t just keep doing the same thing, and neither can I.”

So how does Nigel surpass himself in the Dubai video? By jumping out of an airplane. On his bicycle.

We hear the fearsome whip of wind, and Nigel’s yelp of terror fragging into delight

as the parachute opens above him with a stomach-dropping pop. Then the Sahara Desert floor rushing up and Nigel sticking the landing, with Oz-like towers rising in the distance. And then, still in the saddle with Nigel, we’re ripping over the desert toward the city, finally to be scooped up by a Mercedes G-Class full of young male bearded Emiratis wearing robes and blasting hip-hop.

“I had never skydived before,” Nigel says. “But when I got to Dubai I saw that it made a perfect opening scene. I was so wrapped up in getting the shot right that I never thought to be scared.”

The Go series, and Nigel’s other films, depart radically from the standard BMX video, which he calls “BMX porn”: no narration, no context, just the camera, the rider, and the trick. “I grew up watching that kind of video,” he says. “I respect the genre. But after two or three years as a professional rider, I wanted to elevate the game, move beyond, go bigger and deeper. I wanted to incorporate more of my lifestyle and experiences into my content. I want to tell the full story that BMX offers.

Nigel has flouted convention from the start. His first multi-layered, high-production-value narrative launched in 2011. Gatorade, one of his early sponsors, produced an advertising video that depicted Nigel moving through a day both on and off the bike. It was expensively produced, featured the semblance of a fictional plot, and included artful aerial shots of Nigel pedaling over the Williamsburg Bridge. We watch him hanging on the stoop with his pals and, on his bike, pursuing a beautiful, mysterious young woman (the actress Teyana Taylor) driving away in a taxi. Throughout the video, to earn his pay, Nigel liberally hits the Gatorade.

“That project changed the conversation in BMX,” says Glenn Milligan, who directed the video. “For the first time, it made BMX accessible to a mass, mainstream audience.” Within the BMX community, however, the Gatorade video ignited a social-media firestorm. Commenters on one forum, vitalbmx.com, said, I just watched that style profile he was in and it’s fucking shameful...he’s making BMX look like a joke...keep BMX out of the mainstream...As a person he’s full of himself, and I don’t care who you are or what you’ve done with your life. If your ego overtakes your humanity you ain’t worth shit...He’s definitely selling out.

“BMX Hates Nigel Sylvester” read the headline of a 2015 post on psbmx.com. Introducing the piece, blogger Chris Oliver wrote, “I once tried to jump on the ‘I hate Nigel’ bandwagon, but it was full.”

The son of Grenadian parents who emigrated from the Caribbean island, Nigel Sylvester started riding a Big Wheel bike at age 5 in his grandmother’s driveway in Queens. His mother worked as a nurse, his father as an electrician. “It was a strict household-obey your parents, do your homework, don’t fall prey to the streets,” Nigel says. “My neighborhood was hardly the worst, but it wasn’t the greatest, either.”

Many kids from Queens channeled their drive and creativity into music, hoops, or the performing arts; another boy with Nigel’s good looks and easy manner might have

skated by on charm. Instead, he rode his bicycle. From that first ride down his grandmother’s driveway, he was addicted to the freedom of it.

At age 12, Nigel started watching former BMX superstar Dave Mirra (who passed away in 2016) in the X Games. “I thought that was the coolest thing I’d ever seen. I dove into the culture, and fell in love with the BMX lifestyle. I would go down to the bodega and buy BMX magazines. I put BMX posters up on my bedroom wall. I remember my first Dave Mirra BMX bike. Had a 540 Flare frame, chrome handlebars and components, all blue, with a classic seat.”

At the time, there were no skate parks in his borough, and no BMX culture. It wasn’t cool to ride a bike, especially for a black kid. “At school they called me ‘white boy,’ because a black kid wasn’t supposed to ride a bike.” But Nigel recognized that his other interests and talents-music, drawing and design, video, film-could all find expression in BMX. “My bike is like a graf artist’s spray can, or like a mic a rapper would use, just a different tool,” he would declare years later.

Nigel rode every spare minute, buds in his ears blowing hip-hop, scoping the rails, stairs, culverts, and underpasses, doing a jump or grind once and then 30 more times until he had it down. He rode mostly on the streets, but sometimes traveled 90 minutes by subway to Union Square park by the East River in Manhattan, where freestyle riders from throughout the city gathered. Nigel rode the ramps and rails all day, fueling on fast-food dollar meals, not getting home to Queens until 3 in the morning. He studied Tyrone Williams, a pioneer of New York freestyle BMX, and other leading New York riders like Edwin De La Rosa and Vic Ayala-the way they performed their tricks, and how they recorded them.

While white BMX rode to a heavy-metal or grunge soundtrack, the largely non-white New York riders moved to the defiant beat of hip-hop. “Freestyle street BMX is a philosophy, a way of defining yourself,” Williams says. “You look at the physical world differently. A flight of stairs isn’t just stairs, it’s a theater for testing and expressing yourself. A straight person sees you grinding a rail and says, ‘What the fuck you doing?’ They don’t understand.”

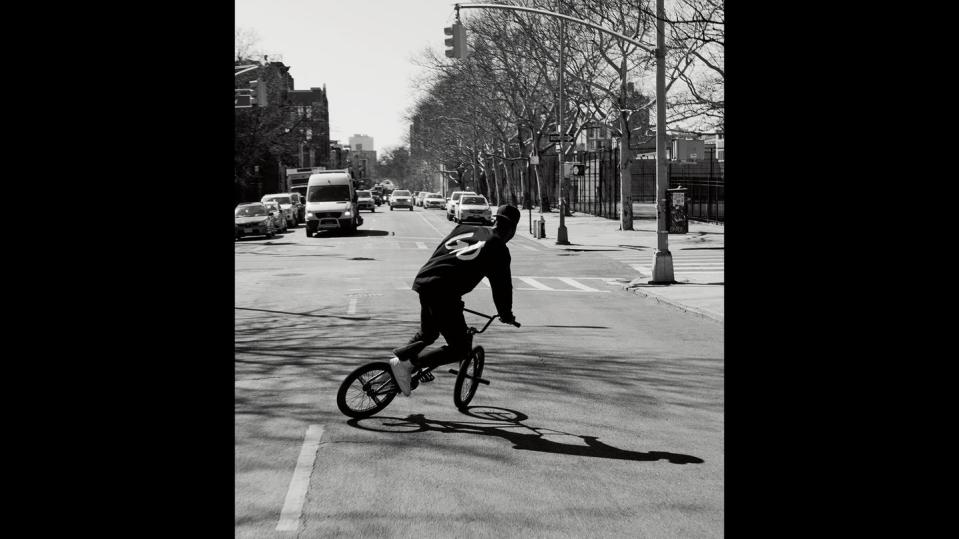

Nigel Sylvester understood. He formed alliances with the city’s top BMX videographers and filmmakers. He started creating his own content and posting on social media. He developed a distinctive persona, and accrued a growing number of fans. “For me, the most important thing is to be fluid on the bicycle,” Nigel says. “I want to look good, have every detail contribute to that fluidity-bike, clothes, shoes, hair, earbuds, and the music coming through them. I’m after the total effect, style and technical skill combined, one feeding the other.”

At age 17, however, with no defined career path in street freestyle to follow, he enrolled at SUNY-Farmingdale on Long Island, pursuing a degree in business administration. The summer after his freshman year, Milligan, the filmmaker, recruited Nigel and three other amateur freestyle riders from New York to travel to Greenville, North Carolina, a center for ramp BMX. “We got to hang out and ride at Dave’s state-of-the-art facilities,” Nigel recalls. “The idea was that, later, four guys from Greenville would come up to New York and ride the streets with us.”

In Greenville, he met Dave Mirra, his boyhood idol. Mirra was the sport’s first crossover figure, an articulate, charismatic spokesman who lent BMX mainstream legitimacy. “Dave immediately sensed the same sort of potential in Nigel,” Milligan says. “They bonded right away. At the time, Dave was getting some ridicule for going too suburban, too corporate mainstream.” Mirra was looking for a freestyle rider from the inner city to fill out his team. Nigel was particularly appealing because he was highly personable and could talk to anybody.

Mirra offered Nigel a contract with his bike company, MirraCo. Back home in Queens, Sylvester told his mother that he was quitting school to become a professional BMX rider. “It created a lot of friction,” he says of his decision. “My first year or two as a pro, I wasn’t making much money and I was still living at home.” He pauses. “Yeah,” he says, smiling. “A lot of friction.”

But Nigel persevered, both on and off the bike. He calculated that he could build a bigger audience through social media than through contests and competitions, and that major corporate sponsorships would yield a higher income than the deals offered by BMX-focused companies. He said yes to every interview request, including those from hip-hop and other alternative-media platforms. All the while, he kept riding the streets and posting content. “Nigel is very smart and very instinctive,” says Brad Lusky, his agent. “From the start, he had a crystal-clear vision of himself as an athlete and artist, and he systematically attacked it.”

Nigel puts the matter more bluntly. “If there’s anything that growing up in Queens teaches you,” he says, “it’s how to hustle.”

Within a few years, the hustle started to pay off. Personifying the edgy, rebellious, no-brakes, NYC street style; possessing an eye for fashion; fluent on social media; articulate; a man of color excelling in a predominantly white sport, Nigel Sylvester drew the attention of corporate marketing executives. During the summer of 2008, when he was 20, Gatorade and Nike signed him to endorsement contracts. Along with Nike, his current sponsors include Samsung, Beats By Dre, G-Shock, New Era, and Ethika.

The mainstream media have proved similarly enamored. In recent years, GQ published a story detailing Nigel’s diet, Sports Illustrated covered how he trains, The New York Times reported on his fashion line, Forbes put him on its elite 30-under-30 list, and ABC television interviewed him, asking how it felt to ride au naturel in the ESPN body issue.

In a video promoting Red Bull energy drink featuring Nigel and Pharrell Williams, the latter says of the former, “He’s not a white boy. He’s a black kid out of Queens. He put his dreams into his sport, and it comes out every time he does a trick.”

“People who gripe on Nigel don’t know him, they don’t realize how devoted he is to BMX, or see how hard he works at it every day,” says Tyrone Williams. “There’s plenty of money in the BMX industry, but it doesn’t flow down to the riders. The overwhelming majority of serious riders put their bodies on the line, risk getting seriously fucked up, for no money at all. Nigel took a look at that and decided on a different route. He cultivated sponsors outside the BMX industry. He succeeded, big time, and that was threatening to a lot of people.

“But it’s not about money. You start riding BMX for the freedom, for the self-expression, but as you get older, life comes at you, and most have to let go of the dream. Nigel’s 30, and he’s still riding, still living his dream. Some people have trouble with that.”

As his fame grew, Nigel’s detractors pounced on seeming trifles. Borrowing a trope from hip-hop culture, for instance, he appeared in a video with a scene depicting him peeling bills from a fat wad of cash. The message-board trolls said that proved Nigel Sylvester was only into BMX for the money.

The vitriol has subsided in recent years, but still surfaces. “Just this morning, a guy posted a comment,” Nigel says, before his ride at Coleman skate park. “BMX can be such an anti-culture, a negative culture. A lot of people want to keep it niche. I can’t cater to that. People calling me a sellout are confused. Isn’t it everyone’s dream to perform your sport, your trade, your business, your art, at a high level, make a good living at it, provide for your family, and see how far you can extend and improve your craft?”

At other times, however, Nigel waxes less philosophical. In an interview published on the website Nylon in June 2017, for instance, he gave vent to his anger. “So, to the purists who think I sold out: fuck that and fuck you! Because a lot of people could never imagine what I’ve went through. I’ve faced racism my entire life. I’ve traveled the world and dealt with it on many different levels.”

Growing up in Queens, Nigel says, he encountered racism from his peers. It didn’t stop when he got older. “The world has a conception of what a BMX rider should look like, and I’m definitely not it,” he says.

And to this day, when he rides the streets in some neighborhoods of New York City, Nigel endures hostile stares and police-car surveillance; the standard harassment that young black males experience in America. Even the bill-peeling episode is instructive. When a white rider behaves loutishly in a video, he’s recognized as a free spirit exhibiting the outlaw essence of BMX. Nigel, by contrast, gets skewered for his interpretation of the code.

“People used to say that a black kid from Queens didn’t belong on a bicycle,” he says. “When I started getting successful, the idea was that a black kid from Queens didn’t deserve to have a Nike contract or his own clothing line. When I started to make videos, they said I didn’t deserve to tell stories. Now, some are saying that a black man on a bicycle doesn’t deserve to be an artist.”

The Go Dubai video premiers on an August evening at the Apple Store in the Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn. Apple is hosting the event because much of the show’s production was accomplished using iPhone technology (at the time, Apple was a sponsor)

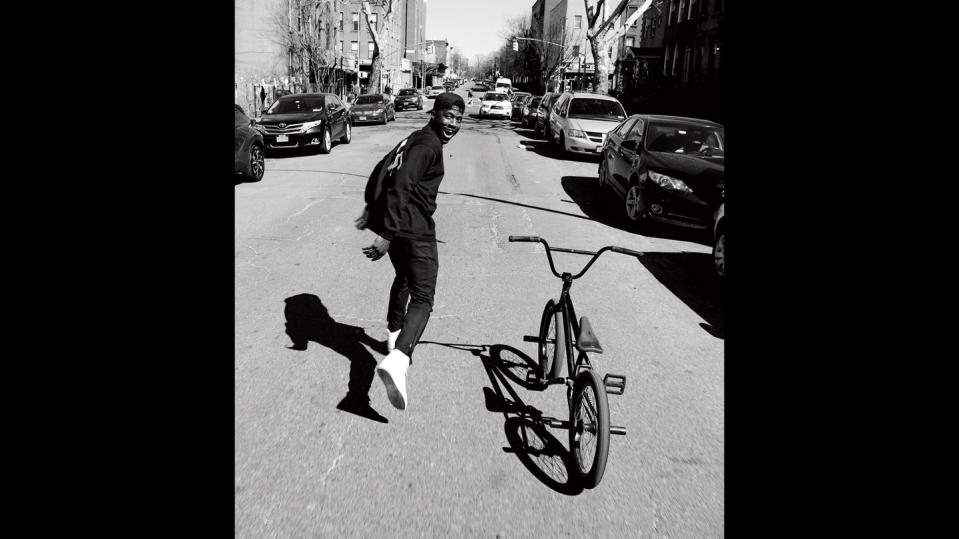

Introducing the film, Nigel takes the stage aboard his BMX bike, twitching out a quick bunny hop that lifts him three feet from floor to dais. He then shows the audience one of his signature bar spins: a flick of his wrists and the front wheel orbits in a 360-degree blur. Nothing flashy, just a taste, a blink and you missed it. Similar to his famous subway-track jump, the trick is distinguished less by its technical difficulty than the unlikely setting in which he performs it.

Nigel dismounts, soaking in the moment, surveying the crowd of 400. Wearing skinny jeans, a black T-shirt, and a black flat-brimmed ball cap bearing the logo of his GO enterprise, Nigel appears intimately at home in the spotlight.

The crowd encompasses various sectors of his life and career: BMX, media, film, fashion, hip-hop, corporate sponsors, family, friends from his old neighborhood in Queens. Tyrone Williams is here. Among non-riders, Nigel sees Mr. Flawless, a high-fashion New York jeweler, and Adrian Sylvester, Nigel’s older brother, sales manager of a Brooklyn car dealership.

The cross-cultural, multi-racial mash-up makes Nigel smile. What other BMX-related event would draw so many square john citizens? And at what other arty New York film opening would you find so many BMX street riders, most of them young men of color?

“I want to show people how it feels,” Nigel says, explaining the motivation behind his work. “I want to show the public how it feels to ride, and I want to show the BMX community that there’s a whole wide world out there to explore.”

The program ends and the crowd breaks into islands of excited chatter. “Nigel got me involved more intensely with the sport,” says a local rider named Kevin Negron, who makes his living as a driver for UPS. “I bumped into him at the skate park and he took notice. He saw my ride needed work and he told me to go over to Post Bike Shop [a Brooklyn BMX shop that is now closed]. They fixed me up with a new frame on his dime.”

Glenn Milligan remembers a video shoot he did with Nigel in New York in 2008. “We were on Oceanside Parkway, the heart of the Hasidic neighborhood in Brooklyn, and Nigel was working a really hard trick, a 180-degree crooked grind. We had been there for a while, and this Hasidic man comes out of his house. He gives Nigel a suspicious look and starts grilling him. Instead of reacting to the guy’s hostility, Nigel smiled at him. He explained what we were doing. He crouched down and did a fist bump with the guy’s little kid.

“The guy goes into his house and comes back out with a popsicle for Nigel. Pretty soon there’s a crowd of a dozen men in their side locks and black hats watching Nigel ride, and cheering him on. To me, that scene was vintage Nigel Sylvester.”

Coleman skate park: a postage stamp of concrete tucked between a ball diamond and a pillar of the Manhattan Bridge. On a Sunday morning two days after the GO Dubai premiere, a flock of skateboarders works the ramps and stairs and rails, with a lone BMX rider swooping smoothly among them. A pool of stagnant water, remnant of a recent rain, floods a third of the park; the boarders and rider glide stoically around it. From overhead, through the gray undergirding of the bridge, the boom of subway trains eclipses the whir and clack of the skateboards.

“Drain must be plugged,” Nigel says, nodding to the pool of water. He’s wearing jeans, a yellow T-shirt, and a pair of black Air Jordans. No hat or helmet. “That’s too bad, but riding in the city, you learn to adjust. Life comes at you-rain, traffic, no trespassing signs, security cameras. You don’t get discouraged, you don’t get frustrated. You adjust to the environment.”

One day last week near his neighborhood in Brooklyn, he says, feeling stale after long hours editing the Dubai video and attending to business details, he put on headphones and started to ride. Familiar venues for tricks appeared subtly new; a rebuilt stairway, an elevated ramp, a recently planted tree or shrub. While grinding a rail, Nigel recalled working the same spot years earlier. The place had changed and he had become a different rider, with surer command of his craft, but less need to prove himself.

“Used to be, when I was coming up, I’d ride morning till night, 8 hours a day, 9 hours. Now I might do 90 minutes a day on average because I’m so busy. That’s cool. That’s part of the change, part of what’s new. But BMX is still my therapy. I can put on my tunes and get away from the phone, away from the merch and Instagram and tweets.

I don’t know what I’d do, who I’d be, if BMX wasn’t the number-one thing in my life.”

His ride this morning will be a get-out-the-kinks session, the equivalent of a musician

running through his scales. Inserting his earbuds, Nigel starts his workout by stretching his hamstrings, rolling his neck, and performing a set of squats. As he approaches age 31, he’s more mindful of his body.

Across the pool of dirty rainwater, in the shadow of the great bridge, amid the skim and whir of skateboards, buds planted deep in his ear, Nigel sits on his bike, nodding to the music of his calling. He then shoots down a ramp to pop a 10-foot bunny jump.

For the next half hour he flies up and down stairs, executes a series of jumps, and hops rails for wheel-peg grinds, each sequence a little more challenging than the last. Between runs he returns to his high spot, resting, folding back into his tunes, surveying the park with hooded, hawk-like eyes, half-planning his next sequence but not overthinking, letting the moment dictate his moves.

The morning is unseasonably cool, but soon he’s dripping sweat. He threads each sequence with bar spins, his signature move, which requires lifting up on the back wheel with an explosive jerk of the forearms. He soars off a ramp, executes an airborne 360-degree turn, and sticks the landing.

Concluding the session, he grinds a rail for 20 feet, hits the concrete, and then pulls up on his bar, riding his back wheel for an entire half-lap of the park.

Aglow with the effort, Nigel Sylvester skids to a stop. He says that he enjoys these focused sessions in the park, but the street ride remains his baseline, where it starts and ends for him. “As I move around the city, I’m always hunting,” he says. “I’m always searching for a handrail or ledge or bench. It happens when I’m riding my bike, when I’m walking to the store, when I’m sitting in an Uber, when I’m waiting for the subway. It’s second nature. I can’t stop.”

Nigel pauses, thinks for a moment, then smiles. “No,” he says. “I just can’t stop.”

('You Might Also Like',)