A dad forgave the man who murdered his son. Then he became his mentor

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Azim Khamisa was standing in his kitchen on the night of Jan. 21, 1995, when the phone rang.

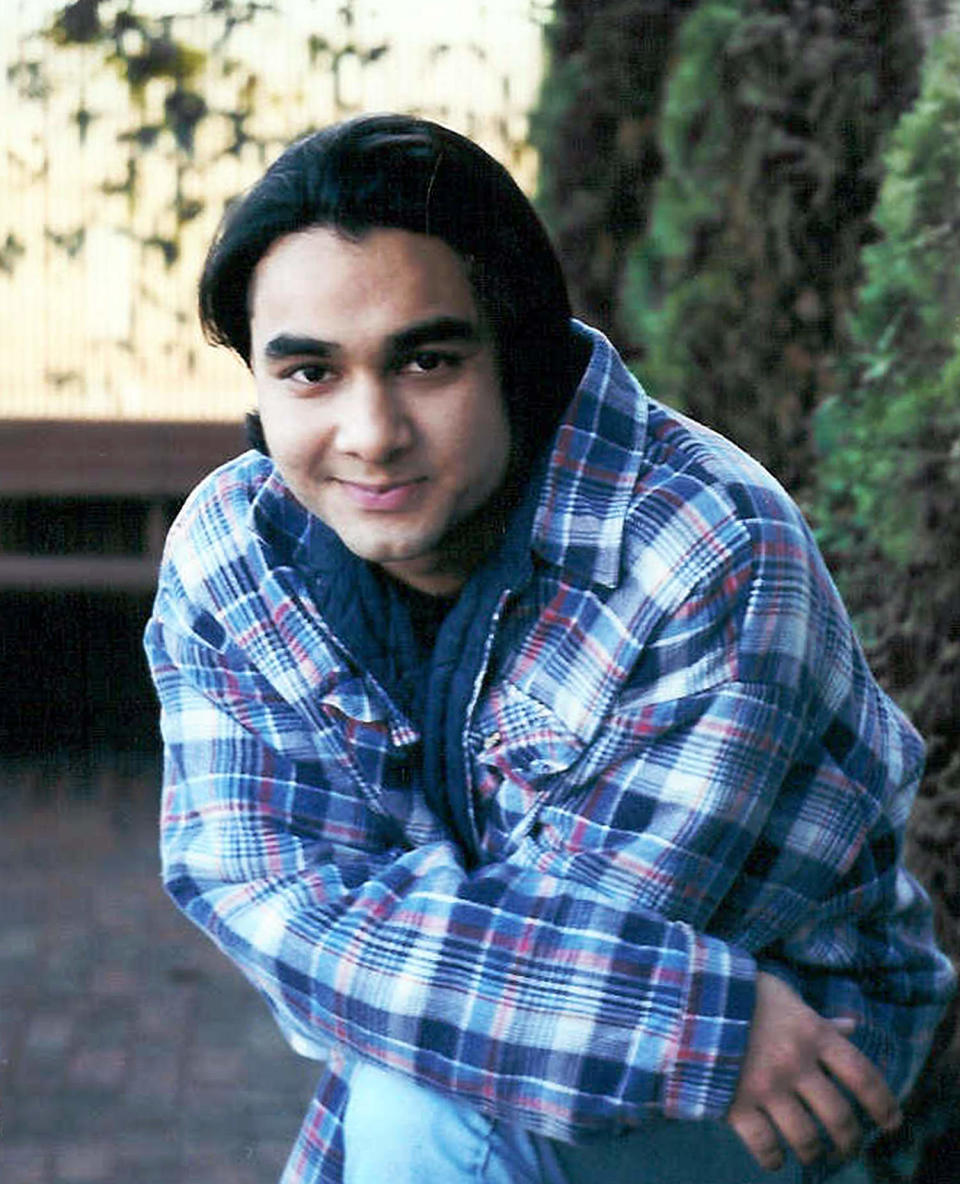

It was a homicide detective who had terrible news. Khamisa’s 20-year-old son, Tariq, a journalism major at San Diego State University, had been murdered while making a pizza delivery.

“My knee jerk reaction was, ‘This can’t be right. It has to be a mistake,’” Khamisa, 75, tells TODAY.com. He hung up and dialed Tariq’s number. Surely, he would answer.

Instead, Tariq’s live-in girlfriend, Jennifer, picked up the phone sobbing. Earlier that evening, Tariq was lured to a bogus address, then ambushed by young gang members from South Central Los Angeles as part of an initiation ritual.

“I lost the strength in both of my legs and I collapsed to the floor,” Khamisa says.

Three days later, a baby-faced 14-year-old named Tony Hicks was in custody. The eighth grader pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 25 years to life.

He became the youngest person in California to be charged as an adult.

‘The decision to pull the trigger was mine’

Hicks, now 43, is matter-of-fact when he talks about his childhood. His mother, a gang member, was 14 when she had him, and his father wasn’t in his life. He lost three young cousins to gun violence. Hicks joined a gang in sixth grade because, as he puts it, “that’s what people in my family did.”

“It was normal to see someone get shot,” Hicks tells TODAY.com.

There is pain in Hicks’s eyes when he recounts the events of Jan. 21, 1995. He had run away from his grandfather Ples Felix’s home that morning, after they argued about him skipping school and drinking. A latchkey kid before moving in with Felix, Hicks says he had no respect for authority.

“That was when I decided I was going to commit myself to the only family I thought I had left, which was my gang peers,” Hicks says.

That evening, when Tariq refused to turn over the pizza or his cash, an 18-year-old gang member urged Hicks to pull the trigger.

“Ultimately, the decision to pull the trigger was mine. I didn’t want to be seen as weak or ineffective amongst my gang associates,” he says. “But I’ve come to realize that the decision was also rooted in my anger and disappointment with how my life had turned out.”

Choosing to forgive his son's killer

“My friend said to me, ‘I hope he fries in hell,’” Khamisa recalls. “I don’t see it that way. I see that there are victims on both ends of the gun.”

Khamisa practices Sufism, a mystical form of Islam, and it is customary to take a 40 day mourning period following a death. At the end of the 40 days, it is believed that the spirit moves to a new consciousness in preparation for its next journey.

During that period, Khamisa prayed, wrote and meditated for hours at a time.

Tariq’s death “was like a nuclear bomb had gone off in my heart,” Khamisa says. “When the explosion subsided, God sent me back with the wisdom that my son wasn’t the only victim.”

Khamisa’s spiritual advisor recommended that he do “good, compassionate deeds” in Tariq’s memory, as these acts of kindness “provide high-octane fuel for the soul’s forward journey.”

Nine months later after losing his son, Khamisa, an investment banker, started the Tariq Khamisa Foundation, also known as TKF, a restorative justice organization and mentoring program for at-risk youth.

One of the first people Khamisa hired was Hicks' grandfather and guardian, Ples Felix, the very person Hicks had fought with the morning of Tariq's death. Felix, a retired Green Beret who has a Bachelor’s degree in political science, had tried to keep Hicks away from bad influences. He was grief-stricken, just like Khamisa.

Khamisa says he never had any doubts about reaching out to Felix and working with him.

“I lost my son and Ples lost Tony, who was like a son. Tony calls him Daddy,” Khamisa says. “I said to Ples, ‘I can’t get Tariq back and you can’t get Tony out of the criminal justice system, but what we can do is make sure other parents and grandparents don’t have to suffer the way we are.’ We can stop kids from killing kids.”

Meeting his son’s killer

It took Khamisa five years, and a lot of prayer and meditation, until he felt ready to meet Hicks.

“I wasn’t sure how I would react when I came face to face with the person who actually pulled the trigger on my son over a lousy pizza,” Khamisa says. “I had to spend thousands of hours on meditation before I could go see him. For the first couple of years, he was using his bravado as a gang member.”

Khamisa says he asked Hicks some “very tough questions,” and Hicks answered them honestly. He was more mature and self-aware than Khamisa expected him to be. The moment that changed everything, Khamisa says, was when he and Hicks locked eyes for an “uncomfortable amount of time.”

“I didn’t see a murderer,” Khamisa says. “He was polite, he was remorseful, he was articulate. He had transformed himself.”

“I wasn’t expecting any of that,” Khamisa adds. “He was a likable kid.”

Before Khamisa left Folsom State Prison, he made Hicks an offer. He gave Hicks the promise of something he’d never had before: a purpose.

“I said, ‘When you get out, you can come work at the Tariq Khamisa Foundation,” Khamisa says. “We’ll have a job for you.”

Believing in life after prison

As Khamisa made his way out of the maximum-security facility outside Sacramento, California, he says he was “a lot bouncier” than when he walked in.

“I had completed my journey of forgiveness,” he says. “It was as if a big albatross had come off of my shoulders.”

The next day, Felix told Khamisa that his grandson had done a complete 180, seemingly overnight. His grandson sounded happier. Hicks didn’t feel he deserved Khamisa’s forgiveness, but he no longer believed he was going to die in prison.

“I grew up in prison with guys who had already been there for 35 years when I arrived,” Hicks says. “No one talked about their future, and suddenly I had a responsibility. I wanted to prove to Azim that I was worthy of it.”

Hicks, who as a little boy dreamed of becoming a scientist before the gangs took hold, aced his GED test, Khamisa says, and began reading anything he could find. He also began blogging for the Tariq Khamisa Foundation.

“I will forever carry a great amount of shame and guilt for murdering Tariq, as well as for the mind state that I held onto long after that night,” Hicks wrote in one post. “But where my immaturity caused me to run away from the shame and guilt of my actions, I am now motivated by the knowledge of the pain that I’ve caused and a sense of responsibility to make amends to those I’ve hurt and attempt to atone for the life I’ve taken.”

Khamisa and his daughter, Tasreen, advocated for Hicks’ parole in 2018.

“I explained to the commissioner that Tony has work to do — not behind bars, but at the foundation,” Khamisa says. “I knew he was going to save a lot of kids.”

In April 2019, at age 39, Hicks was released from prison.

“I think I’d still be incarcerated if it wasn’t for Azim,” he tells TODAY.com. “Azim’s forgiveness and my grandfather’s unwavering support kept me connected to my humanity while I was in prison.”

Hicks’ transition back into society wasn’t easy. He had spent more than 24 years behind bars, and had never lived on his own or paid bills.

“I’ve had to temper my expectations by a lot while rediscovering the world,” Hicks wrote in a blog entry on the foundation website in 2019. “Trying to find work and being turned away, adjusting to the fear of learning how to drive a car, reconnecting with family with distance between us. But I am one of the fortunate ones.”

Today Hicks works as a plumber and serves on the board at the foundation. He and Khamisa speak to thousands of at-risk young people each year. Hicks says he considers Tariq’s sister Tasreen as his sister, while Khamisa is like a dad.

He says he’s still working to forgive himself for murdering Tariq.

“I love Tasreen, I love her kids. I love Azim,” Hicks says. “I can’t look at them and not think about what I took away.”

“Forgiveness is a muscle that I have to exercise every day,” he adds.

Khamisa has written five books on the topic of forgiveness, finding fulfillment and peace. He has been recognized by the Dalai Lama.

It’s been 29 years since Tariq was murdered, and Khamisa thinks about him every day. He often eats dinner with his son, sitting next to his picture and talking to him.

“My altar is right there with his photo and flowers. I light a candle and sometimes some incense and I tell him what’s going on. He talks to me all the time,” Khamisa says.

Khamisa thanks God every day that he chose forgiveness. That choice made a huge difference in Hicks’ life, and also in his own.

“It allowed me to find joy again,” he says.

This article was originally published on TODAY.com