Deepening Empathy and Understanding of the Black American Diaspora Through Food (Guest Column)

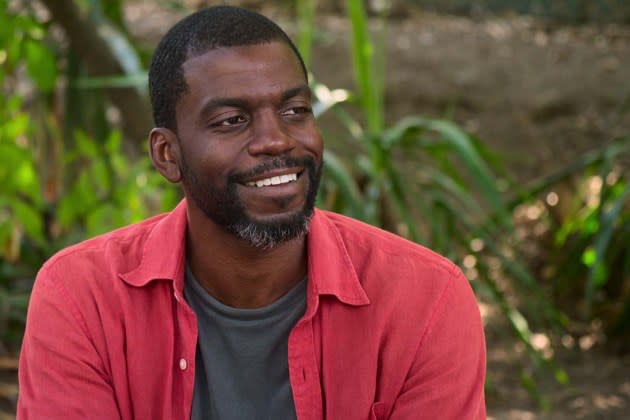

I’ve spent my whole career looking at food from the perspective of origin and, specifically, as an opportunity to deepen empathy among humans. For me, hosting High on the Hog, based on Jessica B. Harris’ text of the same name, has been a dream come true. As we started to discuss the second season, which delves into the Black diaspora as told through a culinary story, the stories of the Great Migration and the Civil Rights Movement happened to be stories that are directly connected to my own family lineage.

When we introduced High on the Hog to audiences in season one, my style of engaging was not really about me as the host; it was more deferential. But as we continued our journey in the second season, we felt we owed it to the viewers to reveal more about their guide and his history. It was a profound revelation for me to think about the reality that my own family lineage is a true microcosm of the Black American story.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Carrie Coon on Her 'Gilded Age' Character: "I Love That People Don't Like Her"

John Early Came So Close to Playing a Gay-Basher on 'Law & Order'

Sharing my grandfather’s story in our exploration of the Great Migration was one of the proudest moments of my life. During the Great Migration, which started in 1910, nearly 6 million African Americans left the plantations of the South and headed north for places like Chicago. During this period of movement and transition, many Black workers stepped up into the working class on trains heading north on luxury sleeper cars, which hired an almost entirely Black staff and created an elevated culinary experience that catered to wealthy patrons. Those men would become known as the Pullman porters.

My grandfather Vernon Satterfield Sr., who died before I was born, was a Pullman porter. He was a brilliant man, yet he was denied his college education on the basis of his skin color despite being accepted on his merit. I knew little about his life, but hearing firsthand stories from Mr. Benjamin Gaines, a former Pullman porter close to my grandfather’s age, helped me imagine what it must have been like. This experience was a gift.

So much of my grandfather’s story is ultimately one of anonymity and a lot of potential that was never met with requisite opportunity. Having the chance to elevate his story in the context of my work in the space of food origins, food culture and personal identity was a deeply profound honor, and sharing it with my own family has been powerful and surreal.

I also had the great privilege of filming the episode “The Defiance” in my hometown of Atlanta. I grew up here, and it’s the place where I first fell in love with food. We explored the deep connection of food to the Civil Rights Movement and how food played a role in mobilizing and funding its efforts, and the notion of the restaurant and Black restaurateurs creating a safe space for a movement to be possible.

I think so much of the Civil Rights story is conflated and flattened in a way that has been distilled down to Martin Luther King Jr. as a Disney-esque character of good and morality. And obviously that is not the case. There were so many activists who made sacrifices for our freedoms, and what’s staggering is that many of these people are still alive today.

I visited three former student activists who planned and executed a Civil Rights operation in the 1960s in an effort to desegregate restaurants and allow Black Americans to dine with dignity. I was struck by their fearlessness and proud sense of purpose as they put their bodies on the line for a larger cause. One of these activists was Georgianne Thomas. As we sat at the historic Paschal’s restaurant in Atlanta, she told a powerful and unnerving story that has stuck with me. Thomas revealed a scar on her wrist from an encounter with a Klansman who put out his cigarette on her body during a protest. It was at that moment that she committed to the cause. She said, “When he burned me, it did something to me, but it didn’t stop me.”

That scene is so profound, not only because of the level of planning and coordination involved in these movement strategies, but because it reveals the great lengths they went to and their determination at such a young age. It was an incredible honor to have been able to sit with them, to hear their stories and to uplift their acts of resistance, which have paved the way for my generation and generations to follow.

Young folks have a way of making history, and it was an important reminder that the people who actively shaped the freedoms we have today, such as voting, are not distant historical figures. They are elders in our presence who are very much alive and filled with lessons for us to learn from. Atlanta has changed so much since I was a kid, but it will always be grounded in the history of Black food, and we have a unique opportunity to preserve this history.

Throughout High on the Hog, I discovered that there’s actually no story that does not involve food. It’s the central part of everyone’s lives, whether or not we understand or acknowledge it as such. If you are an activist like King, and you’ve been arrested and you’ve been in jail where the food is not very good or frequent or healthy or desirable as a form of punishment, that’s a food story. When you are let out of jail and you’re starving, the first thing that you want to do to restore your humanity is have a dignified meal. I often say that food is the mother tongue of humanity. And it is really the only thing that we all have in common as human beings. It’s the most quintessential part of our experience on earth and, I think, High on the Hog is the highest and best expression of this thesis around food origins, empathy and identity.

This story first appeared in a June standalone issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter