‘Father of State Parks.’ Meet the New York man who led KY’s first state park commission

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It was April 7, 1917 when a man born in Syracuse, N.Y. stepped off a train in Prestonsburg, Kentucky and knew, instinctively, this is where he was meant to be.

“Without warning, without a sign or premonition — on his journey up this beautiful valley of Eastern Kentucky he suddenly came to his ‘journey’s end,’” author George Lee Willis wrote in the 1930 biography of Willard Rouse Jillson.

It was in Prestonsburg, Jillson met his wife, Oriole Marie. He had not even lived in Kentucky for two full years before traveling to Frankfort to speak with Governor Augustus Owsley Stanley. He wanted the job as state geologist.

Jillson had the credentials. From 1914 to 1917, he studied geological conditions in New York, Washington and Mount Saint Helens. During this time he took advanced geology courses at the University of Chicago. He was in a class of 12, five of whom would go on to be state geologists in five different states.

In 1919 Stanley appointed Jillson “Deputy Commissioner of Geology and Forestry” and state geologist.

Subsequently, Jillson was appointed and reappointed State Geologist of Kentucky continuously under five different governors: Stanley, Gov. James Black, Gov. Edwin Morrow, Gov. William Fields and Gov. Flem Sampson.

Jillson knew Kentucky like the back of his hand. He spearheaded the Sixth Kentucky Geological Survey, published in 1921, which mapped a great deal of the state’s geological resources (minerals, oil, gas, coal, etc.).

And the sixth survey is considered to have completed more research and development than in “the other eighty years covered between 1838 and 1919 by the first five surveys,” according to a 1933 article in the Register of Kentucky State Historical Society.

What better man was there to lead Kentucky’s new state parks commission?

Kentucky’s state park system

The Kentucky State Parks system was created in 1924 via Senate Bill 306. It was authored by Northern Kentucky lawmaker Sen. Charles B. Truesdell. The bill, signed by Gov. Fields, or “Honest Bill from Olive Hill,” created the Kentucky State Park Commission.

The main duty of the commission was to select suitable and available park areas “with a view to their purchase by private subscription, which are to be turned over to the State for preservation and maintenance,” according to a February 1924 newspaper clipping in the Lexington Herald-Leader.

Notably, no state funds were to be appropriated for the purchase of land; it would have to be done by subscription or gift.

Members of the first commission included Jillson, Thomas Cooper, University of Kentucky dean of agriculture, and Vance Prather, who was appointed by the governor.

As soon as the commission was formed, the people of Kentucky let their voices be heard as to what locales they thought should be part of this burgeoning state park system.

Nearly 300 men signed a petition asking for Old Fort Harrod to be the first state park. There was interest in adding Lake Herrington as a state park, and 22 years before the state park commission was even formed locals wanted to add Carter Caves to such a system.

To note, the first four state parks were: Pine Mountain, Natural Bridge, Old Fort Harrod, and the Blue and Gray (closed in 1933).

Jillson on the commission

In 1924, Jillson authored “Kentucky State Parks,” a report that outlined potential additions for the new state parks system and the feasibility for the state to acquire the land.

The growth of Kentucky’s larger cities and rapid extension of its highway system made this the time to strike, and soon, or “industrial and commercial interests will creep in and make such acquisitions impossible,” Jillson wrote.

So what constituted adding an area as a state park? According to Jillson, no tract should be made a park which “does not present a high type of physical excellence, great natural beauty, or outstanding historic importance.” Other considerations included not adding regions which exhibited the “scarred and defaced artificialities of man.”

What was at the top of the list in 1924 for a state park? Mammoth Cave. Which was ultimately established into the federal National Park Service in 1941.

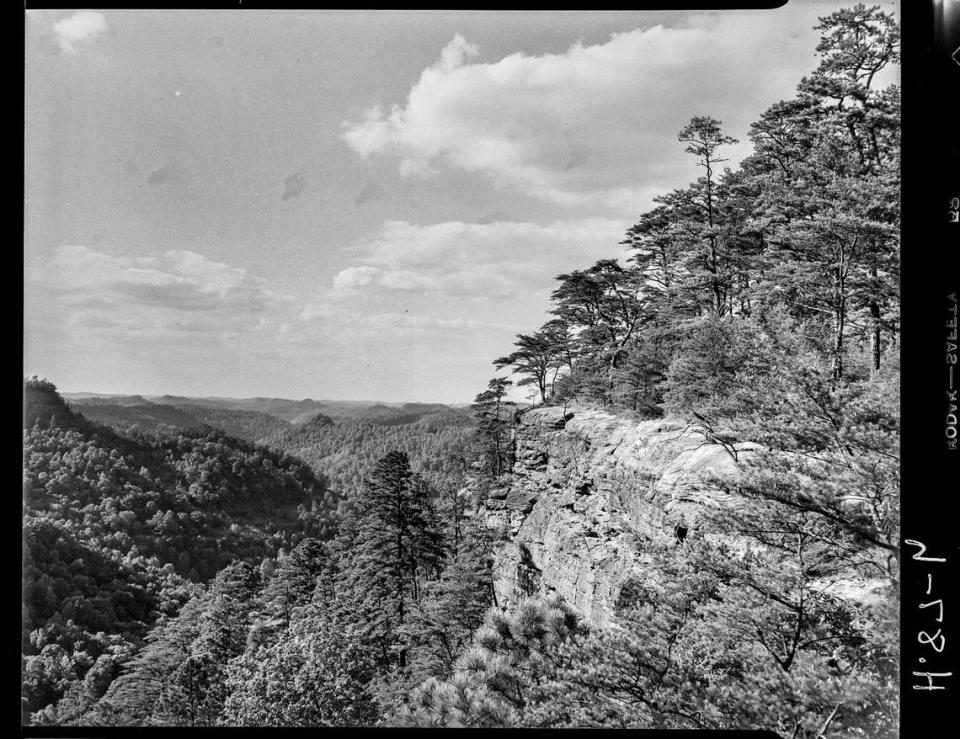

From there the list continues: Carter Caves, Cumberland Falls, Cumberland Gap, Natural Bridge, the “Breaks of Sandy” in Pike County, “In Between the Rivers” in Lyon and Trigg counties, Ohio River Lowlands in Ballard County or Reelfoot Lake in Fulton County, the Kentucky River Gorge and an area “of special significance” in Harrodsburg or Boonesboro.

Pine Mountain was listed earlier in the report, alongside “The Old Kentucky Home in Bardstown,” as essentially being done deals in terms of acquiring the needed land.

Kentuckians likely recognize many of these names as being home to present-day state parks; although not all of them made the cut.

Ironically, Reelfoot Lake was added into the Tennessee State Parks system and Kentucky River Gorge, better known as Red River Gorge, is a designated geological area in the Daniel Boone National Forest.

The ‘Father of State Parks’

Jillson died Oct. 4, 1975 in Louisville at 85. His contributions to Kentucky were many. An obituary published in the Owensboro Messenger-Inquirer says the Library of Congress contains 244 separate index cards of his work; the UK Library has more than 650 titles.

During his early years in Kentucky, from 1917 to 1933, he published 250 papers on Kentucky geology, land grants, history and more.

The Messenger-Inquirer hailed him as the “Father of State Parks” as being instrumental in the establishment of Kentucky’s first four state parks, and for setting standards used by other states in developing state parks.

Yet even as Kentucky’s state park system celebrates 100 years, it seems to be a footnote in Jillson’s larger career. His biography, while published barely six years after the creation of the commission, hardly mentions his role as chairman. And an examination of his collected papers at the University of Louisville gives scant mention of it either.

Given the numerous books, reports, papers and addresses published under his name, perhaps Jillson simply did not consider this to be part of his larger legacy. However, he clearly understood the importance of Kentucky’s state parks for future generations.

In the preface to his 1924 report he writes, “Mere words can never adequately describe the many points of natural beauty in Kentucky…Here are the natural parks awaiting State custodianship. Their acquisition and preservation by the Commonwealth, constitute a service in which we may all unite with pride and enthusiasm–assured in advance of an appreciative posterity.”