It's My First Solo Christmas and I'm Dreading It

After losing both his parents, Jackie Summers wonders how he'll get through the holidays he'd always held so dear.

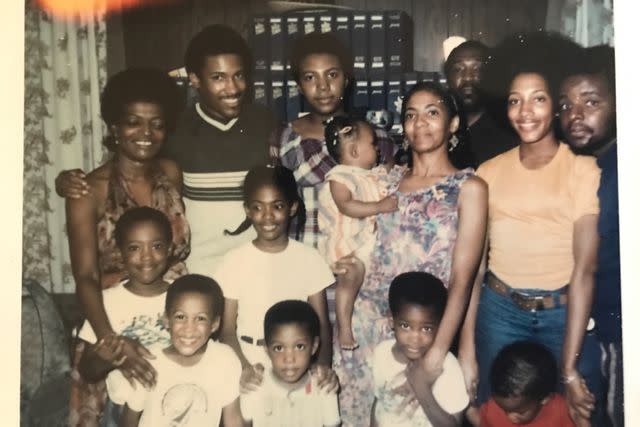

Courtesy of Jackie Summers

I hosted my first orphan’s dinner 25 years ago. As the steward of the family recipes, Mom — herself the daughter of a chef — began my kitchen tutelage when I was the tender age of 10. Initially I was tasked with simple things: properly dicing garlic and onions, tasting for seasoning, and cleaning as we cooked. As I demonstrated aptitude and earned respect, my responsibilities expanded. Eventually I was trusted with the all-important grocery run, calculating the right amount of food required to properly stuff the expected number of guests. Dish by dish, and under her strict supervision, Mom turned over the preparation of holiday feasts to me.

Learning to prepare scrumptious banquets however, was just preliminary. Growing up in a multi-religious household meant all holiday celebrations were non-denominational. More than copious amounts of butter and adroitly sprinkled paprika, it was always the spirit of family that permeated our gatherings. It was never a surprise to see extended family and friends at our table. We didn’t have much, yet we were raised to believe that whatever we had was enough to share with someone in need. For us, the holidays were a celebration of togetherness.

RELATED: When Nanner Pudding Means Everything Is Going to Be OK

They were also an affirmation of the saying: “Friends are the family you choose.” One year, after I’d taken over preparing the entire meal, our party consisted solely of my parents and myself. Sitting fireside and eating homemade sour cream pound cake, my Dad asked me what I was thankful for that year.

“I am so thankful” I replied “that you didn’t invite my idiot siblings. They get on my last damn nerve.”

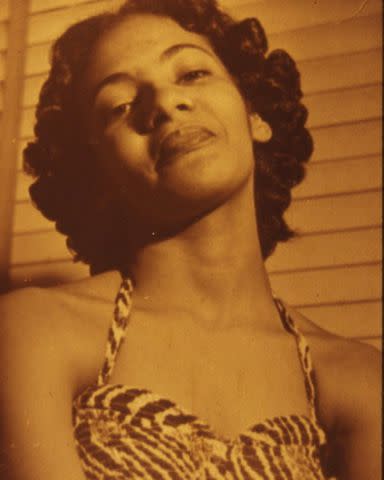

Courtesy of Jackie Summers

The chiding I got for my sass was deserved. It also opened the path for me to begin filling in empty seats at our dinner table. I knew so many who, for various reasons (none of them my business) seemed to have nowhere to go on holidays. So I began inviting my friends to my parents home for holiday meals. Close friends with sweatpants and no plans could crash the Orphan’s Dinner, where they could sup on meticulously prepared dishes, listen to Mom’s wisdom, and hear Dad (after much cajoling) tickle the ivories, all while scarfing down sweet potato pie and homemade whipped cream in front of a roaring fireplace.

It was idyllic for a while. Then my Dad died.

The awareness that everyone eventually loses their parents is little comfort when it finally happens to you. After Dad died, Mom somehow cherished every meal we shared — no matter how small — even more than before. As did I; the epiphany of realizing, posthumously, that the last Thanksgiving dinner I enjoyed with my Dad would be his last, only reinforced feelings of impermanence. Every moment with Mom mattered that much more.

RELATED: It's Jackie Summers' Time to Shine

And so it went, for two decades and change, treating every meal with Mom like it might be our last. Cramming every possible moment with loved ones and scrumptious food and laughter like time was our succulent Sunday goose. Lavish spreads to challenge even the most ambitious elastic waistbands were prepared, in willful defiance of Mom’s advancing years. In my heart, I knew I was stockpiling memories for a dreaded yet inevitable future.

Then Mom, having never been hospitalized previously, spent four entire months in one calendar year in and out of intensive care. She was 93.

Courtesy of Jackie Summers

Last fall when I brought Mom home from the hospital, I knew. I hired a nurse to spend a few hours with her every morning and every night. We hired contractors to restructure her house, so she could have hospice at home. And when the last Thanksgiving I’d ever spend with Mom arrived, I was as prepared as a son watching his Mom die can be.

Which is to say, not at all.

The spread of culinary delights I spent decades mastering was scaled back to bare minimums. Instead of whole turkey brined overnight in apple cider, with fresh thyme, rosemary, and sage — a single turkey breast, with salt and pepper. A mound of lightly seasoned creamy mashed potatoes now sat in the space once occupied by homemade cornbread stuffing. Even the vodka soaked, scotch-bonnet-infused cranberry sauce, which Mom adored and always requested seconds (and thirds) of, was toned down to its mildest possible version.

RELATED: Cooking Up a Little Christmas Cheer

It was low-key, quiet, and perfect. Mom was blissful, and thanked us profusely for spending precious time with her. Six weeks later, Mom died.

As my disenchantment with manufactured holidays designed to hide painful truths about US history has grown, I’ve become less enamored with the idea of holiday fetes. Although I saw it coming, this season somehow feels unnecessarily cruel. It’s not the food; I’m still more than capable of creating junkets that would embarrass dignitaries.

It’s the reminder of the aloneness.

RELATED: The Telephone Christmas

I’m not a parent — seems I forgot to procreate (whoops). So I have no idea what it’s like to watch a life you’ve brought into the world, naked and helpless, grow strong. A life that’s entirely dependent on you to care for it; to clean it, feed it, keep it safe, ensure its survival. I imagine it’s exhilarating, albeit terrifying and exhausting. The parallels of watching your parents age are not lost on me.

This holiday season, I find myself battling an identity crisis. It’s my first year not being a son. I liked being a son; I was good at it. I liked being their son. And now for the first time in my life, I find myself wishing to be someone I’m not. I’ve nowhere to go and no parents to cook for, and the stockpile of rich, verdant memories I amassed like a dragon hoarding gold doesn’t seem to be quite enough to fill the chasm of their absence. Like the many friends I invited to dine with my parents over the years, I now find myself in the unenviable position of being an orphan during the holidays.

This year is my first orphan’s dinner. If anyone could lend me a protocol manual I’d be much obliged.