'Ghost' of ancient river-carved landscape discovered beneath Antarctica

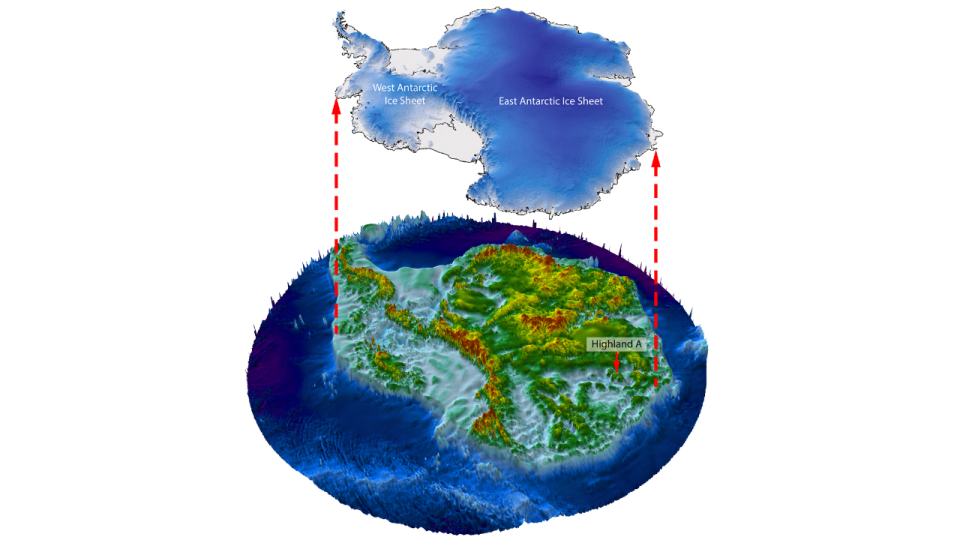

Beneath East Antarctica's undulating ice sheet lies an ancient, river-carved landscape that provides a perfect snapshot of the region before glaciers covered the continent, a new study finds.

Although most of the land buried under the ice sheet was eroded over the eons by moving masses of ice, satellite data show that a patch adjacent to the Aurora and Schmidt subglacial basins has remained largely unscathed for up to 34 million years.

"We could see that there was something like the ghost of the landscape under the ice," study co-lead author Stewart Jamieson, a professor of geography at the University of Durham in the U.K., told Live Science. "At some point in the past, there's been rivers flowing over it, which automatically must mean that it's from before the ice sheet grew."

Jamieson and his colleagues used preexisting data to map bumps and troughs on the ice surface mirroring changes in elevation in the underlying landscape. These slight gradients revealed a "little island of topography" buried 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) below the surface and three "blocks" of land separated by U-shaped valleys, Jamieson said.

Related: Earth's crust swallowed a sea's worth of water and locked it away beneath Pacific seafloor

The blocks likely formed a continuous landmass, he said. But when the ancient supercontinent Gondwana, which included Antarctica, broke up during the Cretaceous period (145 million to 66 million years ago), tectonic forces may have ripped them apart. "As part of that pulling away of continents, it's probably stretched our landscape and broken it up into those three blocks," Jamieson said.

When the climate cooled following the Cretaceous, ice caps may have formed on top of each block and carved out valleys as the ice melted and water trickled down from the peaks. "Those rivers were probably flowing towards the coast, which is a few hundred kilometers away, at a time when that coast was opening up," Jamieson said.

The big ice sheet that still covers Antarctica today grew around 34 million years ago and smothered the entire continent, according to the study, published Tuesday (Oct. 24) in the journal Nature Communications.

"Suddenly, that landscape is frozen in time," Jamieson said.

But not all of East Antarctica was preserved beneath a frigid blanket. In places where the ice grew thickest, the weight that piled onto the land caused melting at the base of the ice sheet, giving rise to a thin layer of water. This allowed the ice to grind over the land and erode it over millions of years.

In the newly discovered location, the ice didn't grow thick enough to create a layer of water, Jamieson said. "When you look at the pattern of ice flow in the region, it's sort of going faster on either side of our landscape. But then on top of our landscape it's going really slowly, and that's because it's basically frozen to its bed," he said.

RELATED STORIES

—Discovery of 'hidden world' under Antarctic ice has scientists 'jumping for joy'

—City-size lake found miles below Antarctica's biggest ice sheet

—Enormous river discovered beneath Antarctica is nearly 300 miles long

Whether this landscape has stayed completely the same for 34 million years is somewhat opaque. Periods of warming that deglaciated parts of East Antarctica until about 14 million years ago may have caused some of the ice above it to melt, Jamieson said.

"What would be really intriguing is actually going to that location and drilling through the ice to get a sample of the rock and sediment underneath," he said. "That would be the only way we could confirm the age."

Ultimately, understanding what lies beneath the East Antarctic ice sheet will help researchers predict its fluctuations in a warming world. "We need to understand the shape of the landscape so that we can understand why the ice is flowing the way it does now and how it might react in the future," Jamieson said.