The legend of the lost ship of the desert

From the archive: This story originally published in The Desert Sun's Desert Magazine in December 2019. John Grasson died in December 2021.

There's a legend in the California desert: A long-lost treasure ship lays buried beneath the sand.

Some say it's a Viking knarr, a merchant vessel, abandoned by Norse explorers who veered far south after navigating the Northwest Passage.

Others think it's a Spanish galleon, full of black pearls, that made its way up the Gulf of California during the era of conquistadors.

There are reports of sightings around the Salton Sea and Imperial Valley, extending as far south as Mexico’s Baja peninsula, though firsthand accounts are rare. Most historians and archaeological experts are skeptical. To naysayers, it’s simply a myth passed down through oral and literary tradition.

But just because a ship hasn’t been found doesn’t mean it isn’t out there.

At least that’s what the believers say.

Part 1: Treasure hunters comb the Salton Sea for bounty

John Grasson was born in California gold country, but he’s going on 13 years of searching for pearls.

Down the back hallway of his Banning home, inside an office wallpapered with Norton Allen maps of the surrounding deserts, skeleton figurines stand in rapt silence atop his wooden desk. For the 62-year-old mattress salesman, their bones aren’t so much relics as they are a calling.

“I’m beyond obsession,” says Grasson, who usually wears a brown fedora pulled low over his pale face. “This has been the main focus of my life for years.”

For nearly two decades, Grasson has been searching for a ship buried deep in the sands of the Southwest desert. Magazines, newspapers and books across the world have long perpetuated the idea that a nautical relic could lay buried beneath the crust that tops the region’s floor. In 1870, Philadelphia’s Evening Telegraph called it “a marvellous story” about “a ship high and dry on a Colorado Desert – billows of sand beating about her.” Across the pond, British publishing house Chapman and Hall released poet Joaquin Miller’s book of verse The Ship in the Desert in 1875.

Some believers are convinced of its existence because of the way water once covered this arid landscape. Most scholars don’t entertain the notion. These days, it’s all television crews and myth busters with their metal detectors in the wind.

Grasson splits his time between a dirt-beaten, black Jeep with a LSTSHIP license plate and his computer, where he posts stories and tips to his website lostshipofthedesert.com. A member of the fraternity E Clampus Vitus, which is dedicated to preserving the heritage of the American West, he’s followed leads into libraries, historical societies and homes across the Golden State all the way down to the U.S.-Mexico border. The commitment, he says, has superseded "married life, riches" and being “successful at work.”

"I don’t regret giving up anything, if I did," Grasson adds.

The former publisher of now-defunct Dezert Magazine isn’t in it for the treasure. He simply wants to discover the origin of the lore.

"Ninety-nine percent of all legends have a story or a base in truth," Grasson explains.

That's what keeps him going. Plus, he’s in way too deep to turn back now.

The desert wasn't always this dry

Start the journey on the edge of the Salton Sea todayandyou might scratch your head as to how a ship could make its way to this part of the desert. Located more than 150 miles southeast of Los Angeles, California’s largest lakeformed due to a man-made accident in 1905, when the Colorado River broke through irrigation canals and spilled into the Salton Basin.

But how could a ship get to the desert?

Some believers point to the Salton Sea, even though there’s no way to sail to it today.

That’s because another freshwater lake – more than six times the size – used to cover this part of the desert up until a few hundred years ago.

Known as Lake Cahuilla, it filled by way of the Colorado River and stretched over parts of the Coachella and Imperial valleys as well as areas in and around Mexicali in Baja California.

Its outflow channel, which corresponds to the modern Rio Hardy, could have been where a long-lost ship sailed in.

Stand at the Salton Sea today and look closely at the nearby mountains – you can see a faint, white waterline etched into the peaks like a ghostly bezel.

Lake Cahuilla filledat least three times over the past 1,000 years – as recently as the mid-1600s – says Don Laylander, a senior archaeologist with the cultural resources firm ASM Affiliates, who has published numerous studies on the region.

Today, some of its invisible shorelines are dotted with fish traps from two indigenous groups, the Cahuilla and Kumeyaay. While the Kumeyaay now have reservations in San Diego County and Baja California, the tribe's territory once stretched farther north.

"Our people were surrounded by bodies of water on both (east and west) sides," says Ethan Banegas, a history instructor at Kumeyaay Community College in El Cajon, Calif.

The rest of Lake Cahuilla's chronology is murky enough to leave room for debate about the type of ship that could have reached the desert and the origin of the crew onboard. However, its outflow channel compels the imagination: There were periods in which Lake Cahuilla connected to the Gulf of California.

The lake's 'ghost' spurs sightings

That’s enough for believers like Grasson, who likes to say he works “within the grey area of history” to determine whether bits of information fall under possibility or probability. Sightings of nautical wreckage, he says, originate near the desert’s ancient lake. Just a year after the Great Flood of 1862 devastated California, Nevada and Oregon, writer Albert S. Evans was traveling to the Southern California town of San Bernardino when he claimed to stumble upon a ship's remains.

“The moon threw a track of shimmering light” upon “the wreck of a gallant ship,” Evans wrote in The Galaxy magazine in 1870, “which might have gone down there centuries ago when the bold Spanish adventurers … were pushing their way to the northwest.”

It appears Evans’ account from the “ghost of a dead sea” quickly gained an audience – he traveled to the California Academy of Sciences to retell his story later that year. Proceedings from a Nov. 21, 1870, meeting in San Francisco show the academy also got in touch with other parties from Los Angeles, San Bernardino and San Diego. Around the same time, a prospector named Charley Clusker claimed to have found a Spanish galleon near Dos Palmas, a watering station for travelers that's now a preserve on the Salton Sea's northeastern shore.

“Clusker says he saw the ship distinctly through his glass, about a mile and a half distant,” a San Bernardino correspondent wrote for Alta California on Nov. 26, 1870. “She lies on her beam end, her bow, bowsprit, and stern well above the sand."

The account was reprinted in newspapers across the country, from the Chicago Tribune to the Buffalo Express. But in 1871, J.A. Talbot of the San Bernardino Guardian updated the story after he accompanied the expedition, noting Clusker’s mission to retrieve the remains had been “unsuccessful.” The California Academy of Sciences concluded the ship was a “myth.”

But there’s a difference between a myth and a legend. One is rooted in the supernatural, while the other is based on a kernel of truth. To this day, explorers continue to be pulled in by the tides of the lost ship legend – re-reading pages of the past to find clues.

No proof of the ship in maritime records

Some believe the vessel is Spanish, against historical odds. Whispers of a caravel swirl through the Superstition Hills, which rise just beyond the southern tip of the Salton Sea. There are reports of a petroglyph that looks like a European ship carved into Pinto Canyon, a path near the international border, even farther south.

Believers point to a 1933 book called The Journey of the Flame by Antonio de Fierro Blanco, which details how Spanish captain Juan de Iturbe sailed past the Gulf of California to a “sea extending far inland” before losing track of the channel – and the ability to return. The crew “left their ship and its vast treasure of pearls upright as though sailing,” Blanco wrote, “with its keel buried in the sand.”

But “Antonio de Fierro Blanco” was just a pen name for author Walter Nordhoff, who published The Journey of the Flame as a historical novel – not fact, says UC Riverside doctoral candidate and historian Todd Luce. In a 2002 foreword to a new edition, writer Rebecca Solnit said the book could be read as a "veiled self-portrait" or an "Old California romance."

Here's what historians know to be true: Iturbe and another captain, Nicolás de Cardona, navigated the Gulf in 1615. But they likely didn't make it as far as they thought. In the book Cartografía y crónicas de la antigua California, Mexican historian Miguel León-Portilla only places them at Tiburón Island, a little more than halfway up the Gulf.

In fact, the farthest documented voyage by a Spanish ship throughout the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries happened in 1540, Laylander says, when Hernando de Alarcón sailed up the western coast of Mexico and traversed the head of the Gulf. Alarcón then navigated the lower Colorado River, making it at least to modern-day Yuma, Ariz. – abut 100 miles southeast of the Salton Sea.

But Grasson isn’t one to take no for an answer, unless he can disprove a theory himself. When he drove out to the Salton Sea shoreline, he found shells but no ship.

Now, his research is leading him farther south.

Part 2: Is the legendary ship Spanish or Viking?

For Grasson, the legend of the lost ship is like a ball of yarn: He keeps unraveling until a theory is dead.

In the case of Iturbe, for example, he eventually came across the work of American historian Michael Mathes, who said the Spanish captain returned to Acapulco in 1616 – with his ship. After reading that piece of information, Grasson walked around "frustrated and upset" for days.

"It was clearly something I did not want to hear," the mattress salesman wrote on his website, because he had studied the angle "for years."

But Grasson isn't afraid to move on to another thread – or unravel two, or three, or four, at once. If the ship isn't Spanish, he's open to the possibility of a different country of origin – English, or even Viking. There could also be more than one buried vessel, he muses.

You might be wondering how Norsemen could realistically factor into atale about a stranded ship in the middle of the California desert. Understandably so.Vikings settled in Iceland and Greenland starting in the 9th century – and as far south as Newfoundland, on the eastern coast of Canada, around 1000 A.D. The first documented successful journey through the Northwest Passage didn't happen until 1906.

But Grasson has intel about a sighting of a Viking ship by a resident in the Southern California farming town of Imperial, about 30 miles south of the Salton Sea.

And so the story goes...

Imperial farmhand leaves nautical clues

A few years back, Grasson ran into a “friend of a friend” who knew a private collector with an audio recording of a curious 1964 interview conducted by writers Harold and Lucille Weight. In it, farmhand Elmer Carver claimed to have worked for a local hog farmer whose fence was made out of wood from a Viking ship.

Grasson drove 80 miles – twice – to listen to the recording. At first, he'd only been able to furiously scribble down notes on a napkin.

The way Grasson tells it, the farmer’s wife let Carver in on the secret, and he went out to find a stern rising from the ground behind the house. She showed him all the jewels they’d sifted from the sand, including the “coup de grace” – a 2-inch solid gold crucifix with blue stones “believed to be topaz,” Grasson says. The Norwegian farmer, Nels Jacobson, went back and forth to Los Angeles to sell the jewels to a pawnbroker but kept the operation under wraps because of a law that protected archaeological sites, the Antiquities Act of 1906.

"I always find it funny because they mention the pawnbroker's name is Barney," Grasson laughs. "How does that fact survive?"

The San Bernardino County Sun reported in 1912the $137,250 sale of Jacobson's 800-acre ranch and livestock as “one of the largest land deals in the history of Imperial valley." Three years later, the paper described Jacobson as a "rancher who metamorphoses swine into gold."

But there was no word on any actual treasure when a fight over Jacobson's will between his widow and sister made the paper in 1926. Let alone how a shipwreck from centuries earlier could have maintained enough durability to be repurposed into a fence.

Anne Morgan, former curator and head archivist at the Imperial Valley Desert Museum, heard the legend of the Viking ship shortly after relocating to the area from New Orleans.

“First, I was sure that they were just trying to really pull my leg,” Morgan recalls.

“It really had me thinking, ‘OK, clearly this is a test the locals have devised because what would Vikings be doing in the middle of the desert?'” she adds.

But then Morgan learned the region's history, how Lake Cahuilla once stretched its waters over this drought-scorched swath of farmland. A documentary film crew arrived in the area a few years ago, she said, and told her they’d found nails believed to be from a Spanish ship, which they wanted to sendto a maritime expert for testing. (Multiple emails to the production company, UK-based Icon Films, from The Desert Sun were not returned.)

If a ship had been visible in the area, “there would be more records than there are,” Morgan says. Plus, “wood does not last very long around here.”

But Pearce Paul Creasman, an associate professor in the University of Arizona's Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, says wood can survive for an "amazingly" long time in certain parts of the desert, depending on environmental conditions.

While the type of wood can be a determining factor, ships are expected to be "critter-resistant" to marine worms or termites, Creasman says. It's "not uncommon" for entire vessels to last 500 years – in Egypt, buried ships dating back to around 2700 B.C. still exist in good condition, he adds.

But if an area is prone to wet and dry cycles, such as rain, floods or a river that rises and falls, Creasman cautions, the opportunity for preservation is "considerably reduced."

While chasing a phantom, it's best to keep your nerve

Let's say a shipwreck did endure in Imperial. In spite of the Colorado River's undulations, against the odds of a fluctuating ancient lake.

There's still the more flummoxing question: Seriously? A Viking ship?

For this theory to work, Norse explorers would have needed to navigate the Northwest Passage, make a sharp left turn, sail down and around the Baja peninsula, then traverse the length of the Gulf. Also: Find a channel to continue the northerly voyage and ultimately make it to Southern California.

About the series

Desert Sun features editor Kristin Scharkey and photojournalist Omar Ornelas reported this project over the course of two years. Along with a documentary film crew, they traveled from Banning to Imperial to capture how the legend of the lost ship evolved in Southern California. They also made multiple trips to Mexico to learn how oral tradition shaped the legend in Baja. Some interviews were conducted in English. Others were conducted in Spanish, and Desert Sun reporters translated quotes for the story. Scharkey also reviewed hundreds of pages of historical texts, literature, media reports, studies and more.

No Viking ships have been found on the West Coast of America, says Douglas Bolender, a professor of anthropology at the University of Massachusetts Boston, whose research focuses on the Viking Age. And there is no evidence they ever navigated the Northwest Passage, he adds.

"There's really no chance that a Viking vessel would show up in California," Bolender says.

It's an admittedly far-fetched theory, but Grasson points to an account of a crew that stopped at Mexico's Tiburón Island, about halfway up the Gulf. In the 1930s, a Seri medicine man told anthropologists Dane and Mary Coolidge that "white giants" had landed off the coast of the tribe's Sonoran home.

"We called them Ahnt’-tay ah hek’-tahm – ‘Came from Afar Men,’” said medicine man Santo Blanco, according to the couple's 1939 book The Last of the Seris. "They had white hair and were so big it took two fanegas (bushels) of tobacco to fill their pipes. They came in a big ship, in which they lived all the time, and went out in boats to kill whales."

Whaling expeditions are well-documented in the Pacific Ocean, with crews hailing from across the globe. But Blanco's description of the "wife of the Giant Whaler" caught Grasson's attention: "She was whiter than the men and had red hair," Blanco said. "She had big braids down her back."

While the mattress salesman can't definitively pinpoint her country of origin, to him the story could explain how a Viking shipended up in Jacobson's backyard.

So, Grasson looked into property records for the family to narrow down the location of their home. Armed with clues from the Carver recording, he hopped in his Jeep and raced toward coordinates to retrace the farmhand's steps.

Carver said he met Jacobson at a pool hall in town, then "traveled in a southeast direction, crossing the railroad tracks and wash, then some distance due east." From there, Grasson followed the rest of the 2-mile journey – past a barbed wire fence, alfalfa fields and an irrigation ditch.

Off the main highway, he turned down a dirt road where cars rattle before reaching a grove of overgrown trees. There, he found a pirate ship – in all its plastic glory – built in a backyard for kids.

His hunch is the long-lost vessel lies beyond that property. In recent years, he’s taken two camera crews with surveying equipment to inspect the area. He got his hopes up a few times, when metal detectors appeared to go off, but to this day there have been no hits.

“You chase this phantom and then, all of a sudden, ‘This could be real?’” Grasson recalls. “You can’t allow yourself to go there because you’d be dancing for joy a hundred times before if it really happens.”

For now, an invisible X marks the spot at a dirt road intersection where Grasson believes the long-lost vessel might be buried. All he can do is stare into the sun, looking for a ship he can't see.

Treasure hunters who come for California best not miss

Imperial isn't the only place where believers think a Norse vessel is permanently moored.

Farther north, there are reports of a Viking ship sticking out of the cliffs in what’s now Anza-Borrego Desert State Park in Borrego Springs. In 1933, a librarian named Myrtle Botts is rumored to have met a prospector who took photographs of the vessel – and provided directions so she could see it herself.

Botts was a botanist who frequently made the pages of local newspapers, including the Los Angeles Times for her annual wildflower show. But the only "firsthand" account of her nautical encounter seems to exist on a website called the-wanderling.com. The writer claims to have interviewed her personally, noting such details as a "finely carved dragon's head" on the bow.

But on the night Botts saw the ship, the Long Beach earthquake hit, covering "all traces" of the ship, the writer says.

"Convenient," Grasson muses.

Multiple emails to "The Wanderling" from The Desert Sun to confirm the identity of the writer were not returned.

When asked if the library has record of such claims, Julian branch manager Josh Mitchell could only point to a book by Mike Marinacci called Eerie California: Strange Places and Odd Phenomena in the Golden State, published in 2018. And Robbie Porter of the Julian Historical Society said there is "more online" about Botts' ship sighting than in their archives.

Still, focus remained on Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, which sits just west of the Salton Sea.Four decades later, a man named Lawrence Justus sought permission to enter the same public lands for “the purpose of locating certain artifacts,” according to documents obtained by The Desert Sun.

His attorney first contacted the California Department of Parks and Recreation in 1974 and then two years later with a proposal to enter into an agreement with Justus and the Imperial Valley College Museum in El Centro, Calif., to secure an antiquities permit, after which he'd be able to keep "all gold, silver and rare stones."

The state answered back with a resounding no.

But included in California State Parks' files is an old, black-and-white photo of Justus, wearing dark sunglasses and smoking, from an unidentified publication. It reads, "One of the last photos of Larry Justus, who reportedly found the Lost Ship of the Desert."

It's still a mystery if he actually did.

A secret lays buried 50 miles from Imperial

The more Grasson looks at the waterways that once carved pathways across Southern California, the more he doubts a ship as large as a galleon could make its way to the Golden State. He still believes the Viking ship is possible, though it requires “a leap of faith.”

These days, he’s turned his attention across the border.

“It’s not in the United States,” Grasson says.

Follow the Colorado River down toward its delta, and just 25 miles north of the Gulf of California, a dry lakebed called Laguna Salada sits ominously in Baja California’s wide expanse. Today, farmers dot the sparse lagoon outlined by open skies and cracked-earth vistas. But it once teemed with fish and shrimp caught by the Cucapá, the delta’s indigenous inhabitants.

American author Philip A. Bailey detailed a "persistent legend that a three-masted ship is sunk in the sands of the Laguna Salada" in his 1940 book Golden Mirages. "The majority of tales told in the hills report this semi-mythical ship as being a high-decked galleon with rakish masts and broken shrouds swinging in the breeze," Bailey said.

“Laguna Salada (translates to) ‘Salt Lagoon,’” Grasson explains. “I think over the years (the legend) turns into Salt Lake, turns into Salton Sea.”

For modern-day American treasure hunters, the search for the ship can peter out across the border – whether due to the language barrier, fear or something else. Grasson hasn't made a trip due to apprehension, financial reasons and because he's "old and decrepit." Plus, he hasn't pinpointed the ship's exact location and wouldn't know where to start.

But for the last half-century, a memory lay buried deep in the heart of Laguna Salada, less than 50 miles from a wall that now marks an international line in the sand.

Fifty years ago is the last time 62-year-old Cucapá auto mechanic Jesús Antonio Muñoz remembers seeing the ship. “The majority of people didn’t believe me,” he says in Spanish.

Part 3: The legend sets sail in Mexico

In Baja California, the legend of the lost ship begins where the Colorado River ends.

It’s difficult to picture: that mighty waterway flowing across the Mexican desert, a ship sailing against its current past the head of the Gulf.

And yet, conversations swirl about a wreck that disappeared – then reappeared – during floods that intermittently washed out the region. Some residents even claim to own artifacts salvaged from a sunken vessel, rumored to be part of Sir Francis Drake’s fleet.

More in the series

Two years ago, a mysterious phone call sent me searching for a lost ship

5 facts about the lost ship of the desert: What we actually know

When Drake circumnavigated the globe in the late 1570s, there's no indication the English captain entered the Gulf of California. And it should be noted that covered wagons traveling through the desert were often referred to as "ships," Calexico historian Carlos Herrera Sr. says.

Nevertheless, the legend persists. And while it crosses a border, that doesn't mean it transcends the concept of a line drawn on a map. In fact, it’s rooted in the difference between exploration and conquest – a legacy this continent still reckons with.

In other parts of Mexico, shipwrecks aren’t so much a myth as they are reality. Over the past decade, a crew led by Roberto Junco, director of underwater archaeology for the National Institute of Anthropology and History, excavated the remains of a 16th century Manila galleon off Baja's west coast. His team also works in Acapulco, where galleons arrived, and he says they've collected more than 9,000 shards of Chinese porcelain to date.

In the Gulf of Mexico, Junco is part of a group searching for the “Lost Ships of Cortés.” They discovered a 16th-century anchor, believed to belong to Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés, off the coast of Veracruz last year.

Because he prefers to lend "the benefit of the doubt" to legends, Junco says it's possible one of Cortés' early ships – small, 60-ton vessels constructed to explore Baja in the 1530s – could have crossed shallow waters only to be stranded in the desert.

“Some of these early expeditions have shipwrecks that we know nothing about,” the archaeologist explains. “We don’t know where they ended up.”

When it comes to Laguna Salada, neither Junco nor Laylander are aware of any maritime records of historic ships entering the basin. Bailey, the American author of the 1940s,called the possibility "remote."

While it's conceivable that a “shallow-draft” boat could get there, Laylander explains, the timing would have needed to be “just right.” Over time, evaporation would have lowered the lake level, and siltation would have closed the outflow site.

And yet. There is man now living in the Mexicali Valley, about 50 miles northeast of Laguna Salada, who says he saw a ship buried in the lakebed.

Vaqueros warn the ship holds a secret

Far from where he thinks a ship could be buried many fathoms under, Antonio Muñoz, a self-taught mechanic, dug a hole not quite as deep. Amid scattered tires and more than a dozen meandering cats outside his home in Ejido Sinaloa, the pit is just wide enough for cars to drive over, their bellies within reach of his dirt-stained hands.

His suspicion and sense of humor, like the lines in his tanned face, run equally deep. It’s been decades since he remembers seeing three masts – one tall, two short – sticking out of the sand. But Antonio Muñoz can still trace the lines of that childhood memory in Laguna Salada. Slowly, meticulously, he takes a stick to the dust between his yellow-sandaled feet.

He draws a u-shaped ship, lying on its side and half-hidden beneath the crust of the lake. Then a few small circles – “as if for cannons” – in its wooden exterior, which looked similar to but darker than encino, or pine, he says.

Antonio Muñoz says he first stumbled upon the maritime mystery as a boy herding cattle across the basin with vaqueros, or cowboys. But his companions wouldn’t let him near the ship, not even when several chests caught his eye.

“They looked like suitcases," Antonio Muñoz recalls, "but they were made of wood.”

He got closer and closer – the chests bound by chains – before the vaqueros told him to stop. The ship held a secret, they said. It was “cursed.”

Later, Antonio Muñoz learned the story from his family: Seamen aboard the vessel invaded the area, so his ancestors rose up in defense. They buried the ship to conceal the reminder – and out of fear of being "attacked."

Over time, the young boy watched as the hull descended deeper and deeper into the basin. Then it fully disappeared.

“There wasn't much else spoken,” he says.

No one knows where the ship came from

But the earth in that area, prone to floods, had a mind of its own. Locals recall waves of both water and sand, perpetuating a game of hide-and-seek with the ship.

A local farmer, Arturo Guerrero Cortés, also claims to have stumbled upon the wreckage. About 30 years ago, when he arrived in the area, he got lost on a route from the Mexicali Valley. Today, he takes his animals – a donkey, pigs and cows – there in the warmer months, when temperatures in the basin can reach well over 100 degrees.

The front of the ship looked to be “designed for breaking large waves,” he recalls in Spanish. “Nothing that you would really need to be inside the Laguna Salada.”

The 51-year-old farmer seems to know everyone in the area – from the oldermen selling cans of Kern'sfruit juice from their kitchen table, to a neighbor who allows his dog to run alongside pens of baby lambs – and everyone seems to know him. Back in 1995, Guerrero Cortés worked as a groundskeeper and penguin suit-wearing mascot for the Palm Springs Suns, a minor league baseball team, according to The Desert Sun archives.

Local lore claims the ship landed well before the Spanish surveying expeditions, he says. But the chronology of Laguna Salada is even murkier than that of its northern sister, Lake Cahuilla. Its fillings were likely “very frequent and very ephemeral,” Laylander says, making it difficult to determine potential time frames for full stands.

It’s “highly unlikely that any European ‘invaders’ or ‘pirates’ were present” before Spanish explorer Francisco de Ulloa first navigated the head of the Gulf in 1539, Laylander adds.

But out here in the desert, no one seems to agree on the origin of the ship.

Is a trip to Laguna Salada worth the risk?

The vessel may now be buried more than 150 feet under, Antonio Muñoz estimates.

“Even when you get to the highest points in the area, you can’t see it from anywhere,” Guerrero Cortés explains.

But both men remember exactly where they saw the ship.

And they’re willing to return.

It’s a rugged journey, they warn, not without risk. If the salt didn’t erode the vessel, Antonio Muñoz says, quicksand still poses a serious threat.

Residents talk of the swamps that can suck SUVs under. Four-wheel drive is a must, but not a guarantee. In July, local media reported the rescue of a Tijuana family whose car got stuck – and who did not have food or water. Drive through Laguna Salada, and cell service is dead.

The wind whips in the middle of the basin, an example of what geologists call a graben, or a sinking piece of land between fault lines.

Graben, roughly translated, is the German verb for “to dig, to mine, to burrow.”

A grave.

Part 4: Can treasure be found in cross-border clues?

Laguna Salada opens like a mirage, its perimeter a mirror for the surrounding mountains. Find Cuerno del Diablo, or the Devil’s Horn, and you'll find the ship, Antonio Muñoz says.

“The mountains guide me,” he adds.

Salt flats snake through the dry lakebed where old tires and empty Tecate bottles stick halfway out of the silt. The remains of a ballena, or petrified whale, are rumored to be at the base of peaks to the east, Guerrero Cortés says. To unfamiliar eyes, the surrounding sierras can play tricks.

“Whenever you don’t see footsteps, or any markings,” Antonio Muñoz warns, “stop.”

If a vehicle starts to sink, climb out through the window and stand on top of the roof, he advises. His low-riding SUV leaves a trail of tread where water used to roll over the dust.

Other than a chain in the trunk in case anyone needs to be pulled out, the men do not bring shovels. The mechanic and the farmer do not bring hoes, or any other type of equipment to excavate the elusive ship. They’d never dig.

This is Cucapá land, they explain, it’s sacred.

“I have a lot of respect,” Guerrero Cortés says. “We’ve never tried to take anything out or even try to detect (the ship).”

The legend may not be 'as good' as it seems

It’s a crime in Mexico to carry out any type of excavation without permission from the National Institute of Anthropology and History. Antonio Porcayo Michelini, senior research professor for INAH’s Baja California center, declined to share whether or not he’d conducted work about a ship in the area.

“Unfortunately those kinds of stories or legends are not as good as they seem,” Porcayo Michelini said in Spanish. “I have seen many archaeological sites destroyed by looters looking for nonexistent treasures, unfortunately surrounded by fascinating narratives.”

Antonio Muñoz says he’s not in it for any type of treasure. Guerrero Cortés, who sits in the back seat, concurs. When asked about the residents who claim to have artifacts from the ship, the mechanic says he doesn’t think a piece of metal could be authentic. He saw a vessel made entirely from wood.

All of a sudden, a familiar shape appears in the distance – like a mirage, if not for the concave protrusion. A white, u-shaped hull appears dirtied by water and wind. Could this be the end of a centuries-long chase for a phantom? Did someone paint over the wood? Perhaps a recent storm whipped the vessel out of its hiding place? These are the reactions that stem from giving this legend the benefit of the doubt.

But as Antonio Muñoz drives closer, the blur becomes crystal clear. It’s just a dilapidated – yet modern – boat, marooned next to an old fishing spot on the shore of the Coyote Canal. Hope sinks like four tires in the silt.

In the quiet, Antonio Muñoz drives on. It’s difficult to imagine that Laguna Salada made its “most notorious contribution to world history” centuries earlier when Spanish explorer Juan de Oñate’s crew mistook it for the Gulf, according to a study by Laylander. The wide expanse resulted in mapmakers depicting California as an island through the 1700s – a stark difference from the look of the lakebed today, where the only waves kicked up are dust.

Behind the wheel, Antonio Muñoz's curly hair peeks out from the top of the driver's seat. An afternoon sun beats high, but there’s a chill in the air.

Perhaps from the curse.

Mystery mirrors its spot on a map

The legend of the lost ship so often serves as a reflection of its geography.

Just over the eastern mountains of Laguna Salada lies the only Cucapá settlement in Baja recognized by the Mexican government, though members of the indigenous group also live in other parts of the state and neighboring Sonora, according to a 2016 study by Alejandra Navarro Smith, a professor at ITESO, the Jesuit University of Guadalajara.

The settlement is called El Mayor, and Francisco Javier González Domíguez has lived there all his life. He, too, is a 62-year-old Cucapá man – friends and family call him "Kiko" – who speaks of mysterious boats.

He's heard of various nautical legends in the area, including one of a sunken Chinese ship. His mother once told him of a wooden post, which looked like it could be from a vessel, sticking out of the ground – only to be cut down and disappear. He's also heard a story about a Spanish ship that arrived to build a mission, or church, that sailed away after the Cucapá did not share their ambitions.

But he's not familiar with the story told to Antonio Muñoz.

An estimated 6,000 to 7,000 Cucapá lived in the lower Colorado River and its delta around 1600, before the U.S.-Mexico border split their territory in 1848, according to the Arizona-based Cocopah Indian Tribe. When asked about the legend, Cultural Resources Manager Justin Brundin said it’s not part of recorded Cocopah oral histories.

But for Antonio Muñoz, the memory of a buried ship remains.

As he continues the trek across Laguna Salada, the mechanic's rearview mirror holds the reflection of his bushy eyebrows and dark mustache to match. Then the dust begins to settle. The car stops. Antonio Muñoz emerges from his vehicle, stepping out onto the cracked earth where his ancestors once fished.

“Right here,” he says.

The ground looks the same there as it does for miles. There’s no marker, no hole, no indication that a ship could lay buried beneath.

“It’s lost inside,” Antonio Muñoz explains.

In the middle of a ring of mountains, it’s just an invisible ghost – and guttural gusts of wind.

Clues cross between countries but don't meet

Around the time Antonio Muñoz first saw the wreckage in Laguna Salada, the American media continued its captivated pursuit of the ship.

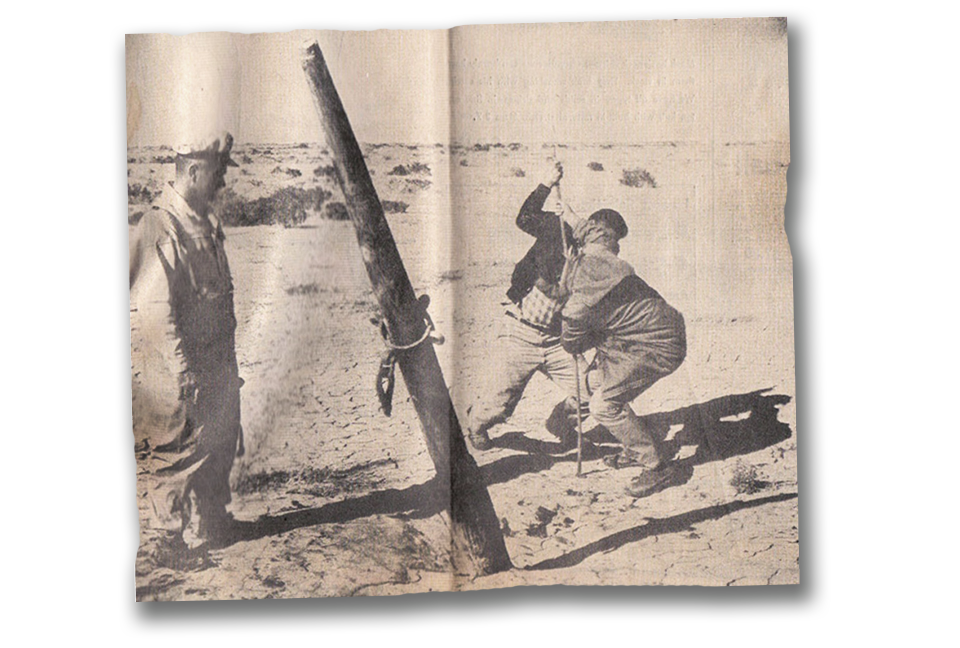

The Imperial Valley Press published a full-page story in 1968, anchored by a black-and-white photograph of two men probing beneath the surface of the Mexicali Valley. Beside them stood amateur archaeologist Morlin Childers, dressed in overalls and a sailor’s cap, next to what appears to be a mast sticking out of the sand.

It’s an odd juxtaposition, this nautical relic emerging from the desert, unbelievable even when standing in the exact spot where two men believe a ship appeared.

When Antonio Muñoz fingers the Imperial Valley Press photograph, he says it could be the same vessel, though he saw a trio of masts. Perhaps the iron collar, which appears to be around the mast in the image, held a perpendicular bar that attached all three to the ship, he adds.

The idea that any number of masts could remain upstanding would be a surprise to Junco, the underwater archaeologist.

Guerrero Cortés, the farmer, points to differences in vegetation and says he doesn’t think the photograph is a match.

Two-hundred miles away, a tattered version of that same article hangs framed in the back hallway of Grasson’s home. He recently made a “substantial financial offering” for the iron collar but won't disclose its location – yet. He's currently writing what he hopes will be "the most complete book ever written" about the legend of the lost ship.

When told about the sightings in Laguna Salada, the mattress salesman said the details confirm a theory he’s been working on for a while now: The ship belongs to English pirate Thomas Cavendish, who captained a vessel called the Content, which set off west from Baja across the Pacific Ocean and then disappeared.

The journey may never end.

But is it supposed to? That question hangs in the air as Antonio Muñoz barrels out of Laguna Salada. For believers, Mother Nature continues to shroud the ship in mystery, leading to relief or disappointment, depending on whom you ask.

“We always try to be on the scientific side of things, not giving in to wild speculation," Junco says, "but personally, I would like to give the benefit of the doubt that these stories can be true.

“Legends," he adds, "lead you on to some kind of historical truth.”

Kristin Scharkey is the features editor at The Desert Sun and the editor of DESERT magazine. Reach her at kristin.scharkey@desertsun.com or on Twitter @kscharkey.

THE TEAM BEHIND THIS STORY

Reporting and research: Kristin Scharkey

Editing: Kate Franco, Julie Makinen

Photography: Sergio Caro, Brandy Menefee, Omar Ornelas

Videos: Sergio Caro, Karina Castañeda, Vickie Connor, Rhiannon Cooper, Rick Marino, Brandy Menefee, Omar Ornelas

Video editing: Vickie Connor, Brandy Menefee

Graphics and illustrations: Kayla Filion,Brady Potthoff, Dorrian Pulsinelli

Digital production and development: Brady Potthoff, Andrea Brunty, Ryan Hildebrandt

Map source: Don Laylander, Antonio Porcayo Michelini and Julia Bendímez Patterson

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: Lost ship of the desert