A Look Inside Fashion's Most Private Archives

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The history of the French monarchy involves a long succession of Louises, one following the other, but in 1648 the country was between kings. Louis XIII had died five years earlier, when Louis XIV was just four years old. The country, therefore, was ruled by the widow of the former and mother of the latter, Anne of Austria, whose frosty relationship with her husband (they wed when they were 14) foreshadowed the one between their great-great-great-great-grandson, Louis XVI, and another Austrian, Marie Antoinette.

Anne, like Marie Antoinette, is a much scorned figure only recently subject to attempts at rehabilitation. As sister to the king of Spain, her loyalty to France was questioned, and she was suspected of having secretly wed her chief advisor. But with a stroke of the pen at Paris’s Palais Royal in January 1648, Anne established a legacy as lasting as anything her husband did: She approved the founding of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, presaging the reputation as patron of the arts for which her child, the Sun King, would be celebrated for centuries to follow.

The driving force behind the academy was Charles Le Brun (he eventually became its director). One of many academy members who worked in artisanal crafts as well as painting, he would later design interiors for Versailles and Paris mansions including the Hôtel de la Rivière, on what is today known as the Place des Vosges. One room Le Brun created for the hôtel, the study, is considered a masterwork of gilding, with the paint applied directly to the masonry. The room was later disassembled and reconstructed around the corner, inside the Musée Carnavalet, the museum of Paris’s history.

Le Brun’s vision and execution, plus Anne’s support—thus was Paris established as Europe’s center of quality craftsmanship and decorative creativity. Yet today, when working with one’s hands is viewed as vocational rather than as professional or creative, that reputation is in peril. The ranks of craftspeople are dwindling to the degree that companies relying on them are in crisis, and the products they make are at risk of being in short supply. At LVMH, home to 75 brands in fashion and leather goods, watches and jewelry, perfumes, and wines and spirits, the company will face a shortage of around 8,000 highly skilled craftspeople next year. In the Île-de-France region, 84 percent of employers of artisans report difficulty in recruiting staff—making it worse off in this regard than 93 percent of all professions.

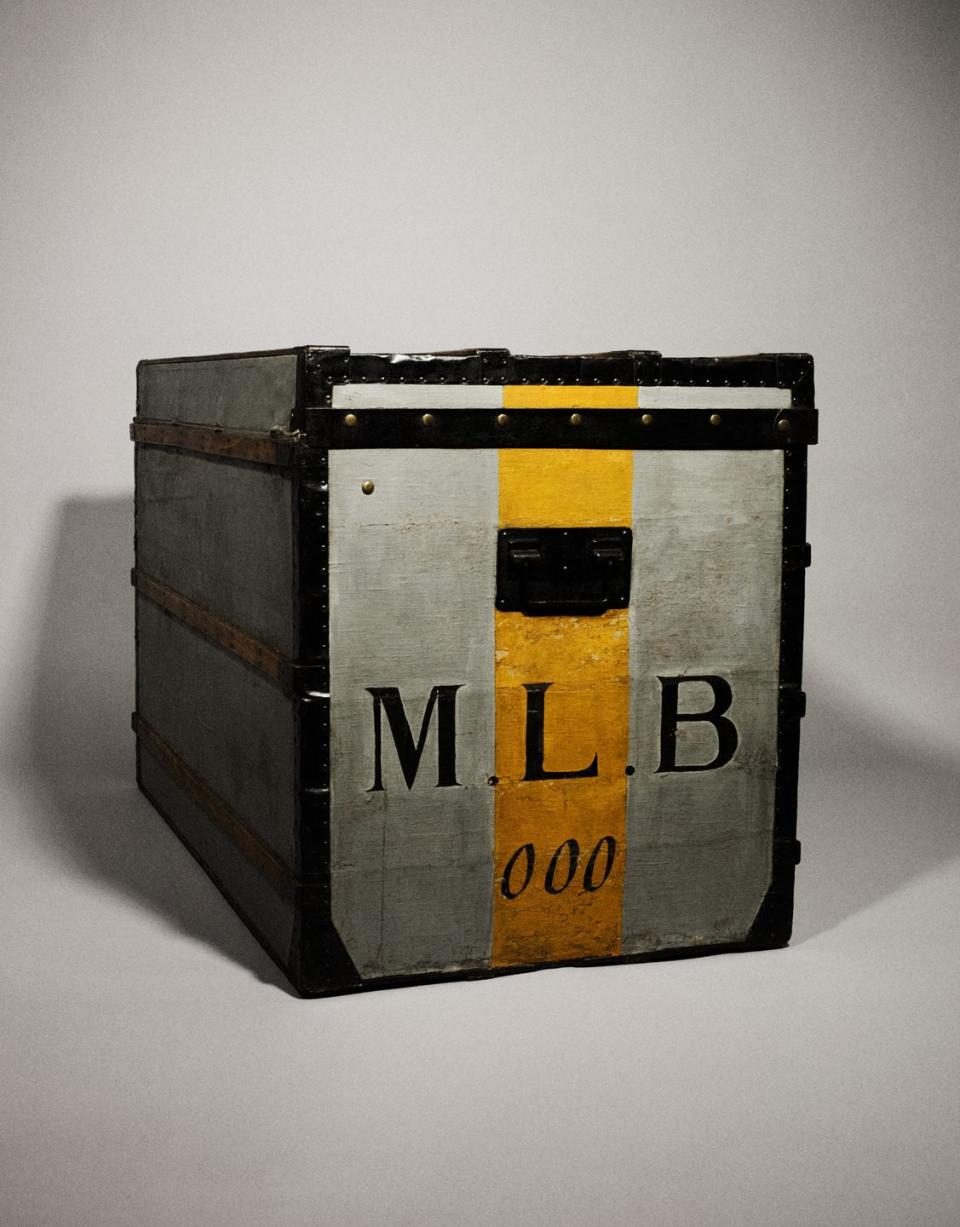

But in Paris these skills are not being allowed to go gentle into that good night. Over three days in April I visited the ateliers of: a metalworker whose fabrications adorn the champagne cave at the Hôtel de Crillon; a glassblower whose work is in the permanent collection of France’s National Center for Visual Arts; a shoemaker who in 1957 built the two-tone, round-toe slingback for Coco Chanel that today remains a staple of chic women worldwide; a glovemaker in an arcade in the 1st Arrondissement whose work is part of the costumes of the Paris Opéra Ballet; the exclusive second-floor gallery of Maison Moynat, which has been making trunks since 1849 and now produces handmade purses so particular that clients sometimes ask for adjustments to the click that the clasp makes when it closes; and the Haute Ecole de Joaillerie, where 65 percent of the country’s jewelers are trained.

These businesses are both thriving and struggling. They are plenty busy with commissions, yet not all can find the apprentices or the materials they need. Such shortages threaten the very reputation on which Paris was built and the business models of the companies that leverage that reputation. “A maison cannot be creative without the crafts,” says Anne Michaut, a professor at the graduate business school HEC Paris. In response to the artisan shortage, LVMH initiated the Institut des Métiers d’Excellence in 2014 to train apprentices in crafts from barrelmaking (Hennessy) to tailoring (Dior Haute Couture) to viticulture (Dom Pérignon). “Craft professions are not valorized enough in the culture,” says Alexandre Boquel, director of the métiers at LVMH. French secondary school graduates often opt instead for careers in the information economy.

Partly, LVMH is a victim of its own success, as luxury brands are becoming more popular due to the upward transfer of wealth in the U.S. and the enormous expansion of the Chinese middle class in recent decades. “When you look at the growth of LVMH,” Boquel says, “we have a lot of tension and a lot of shortages.”

Chanel too is investing in the preservation and development of these artisans. In 2021 the company opened 19M, a multidisciplinary center for métiers d’art in the fashion trade, including textile creation, featherwork, pleating, the bespoke shoemaking of Massaro, and a school for embroidery. In 19M’s stunning five-story building (designed by architect Rudy Ricciotti) in the 19th Arrondissement, existing brands can create a synergy of savoir faire and develop collaborations: The pleating maison can weave some of its work into a Chanel blouse, or the embroiderer can contribute to a pair of Massaro shoes—and display their work to the public.

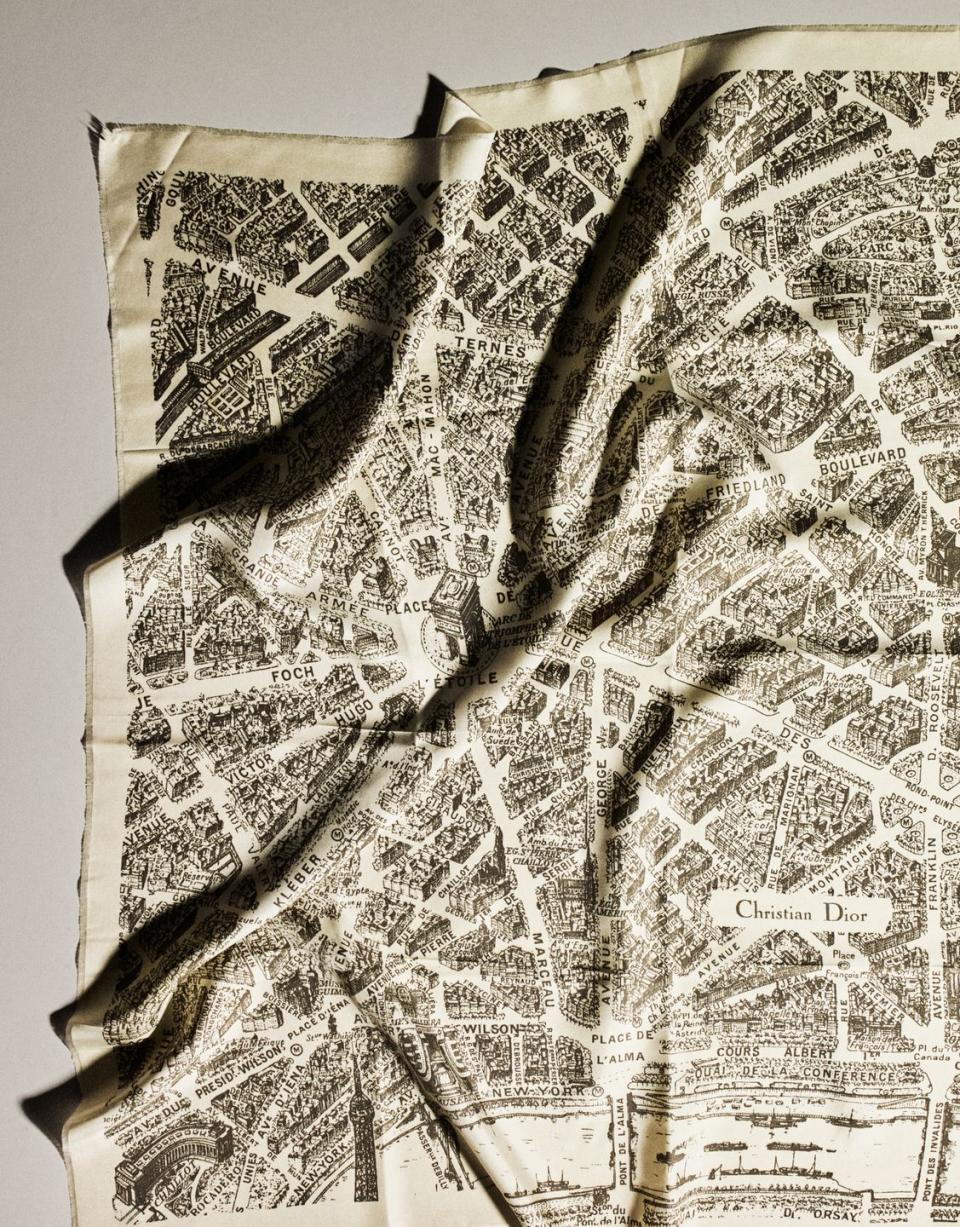

And at Hermès, the so-called “artisanal model” has evolved since the house’s inception in 1837. Now, it’s also seen as a matter of sustainable manufacturing, one that "that inherently leaves a limited carbon footprint,” the company says. Over the years, it’s acquired long-standing partners, particularly in leather goods and textiles, both as a means of consolidating its supply chains and protecting the skills of specialized makers. Production is anchored in France, where Hermès employs some 13,700, including 7,300 craftspeople across its 16 métiers such as leather goods, saddlery, ready-wear and furnishings. As of last year, the family-owned label operated 60 production and training sites across nine regions, each focused on specific disciplines; from 2010 to 2020, it averaged the opening of a leather goods workshop every year, each creating about 300 new jobs. Just last July, a new space opened in Lyon dedicated to silk and textiles, a signature category since Hermès invented the silk carré in 1937.

But the fashion world is not the only area where artisanal culture is facing an existential threat. During my April trip I walked past the former Hôtel de la Rivière and the Carnavalet to the headquarters of Atelier Mériguet-Carrère, a decorative painting and restoration studio. Here, the techniques that Le Brun employed at 17th-century Versailles have been preserved through the generation-to-generation transmission of skills among its artisans. Mériguet’s private commissions include Cartier boutiques and the Paris and Deauville apartments of Yves Saint Laurent, and though it has done many historical restorations, there is one that will serve to establish its cachet: the Grand Foyer of the Palais Garnier, home of Paris Opéra Ballet. Mériguet-Carrère, says designer and Town & Country contributing editor David Netto (himself a master of mixing old and new), is “the top of the top for specialty finishes and faux painting.”

Mériguet’s workshop sits below a 500-square-foot skylight and features two-story columns on which are hung fabric and leather samples so that artisans can see how their work looks at different times of day. Pinned to a board are swatches of fabric with degrees of patterning arrayed left to right from which the craftsmen can view the steps they must follow to replicate a 19th-century wall panel. Painters learn to gild a scalloped inlay according to how its shape and placement in the room relative to the viewer catches the light.

Faux bois, faux marble, and gilding are some of the areas of expertise in craftsmanship (a term more elegant in French: métiers d’art) at the disposal of Mériguet-Carrère’s employees. But these professions are in trouble. “Some of our workers have been here 30 years and will be retiring soon,” says Laurent Gosseaume, the company’s president, “and we need replacements at the same level of savoir faire. This is a challenge for the workshop. Attracting young people to these professions is a strategic matter.”

Gosseaume’s company was the first to come under the umbrella of Ateliers de France, a network of 55 boutique firms specializing in decor, woodwork, ironwork, and other specialty construction trades to foster the imparting of their methods, some developed in the 18th century, to new generations of practitioners. “Decorative plaster, for instance—you don’t have anymore schools that teach this trade,” Gosseaume tells me. “These expertises are an important part of the French economy and reputation.”

Forty miles outside the city, metalworker Steaven Richard maintains an 11,000-square-foot studio, where he and a team of 15 fabricate oxidized copper alloys, bronze patinas, textured nickel silver, wrought iron, and more to be installed as elevator doors, sculptures, and decorative floors and panels for such clients as the Hôtel de Paris in Monaco and Karl Lagerfeld’s studio.

“Paris has a very big and very deep tradition of craftsmanship,” Richard tells me during our tour of the workshop. “There’s a lot of public and private investment to push artisans creatively, to develop and make innovations. With the luxury brands very present here, there’s an opportunity to develop new things—and they can pay. A lot of stimulation results from the meeting of very deep traditions and the necessity to make new innovations.”

In one corner of the shop is the workstation of a semiretired ironworker named Bernard. When he decided to close his own company, Bernard, now 77, proposed to Richard that he provide him a place to continue working part-time in exchange for his 60 years’ worth of expertise and the use of his tools, many of which are no longer manufactured. In this way the atelier has managed to conserve old techniques and diffuse them throughout the workshop. “I didn’t imagine it could be such an interesting model,” Richard says.

It’s an unusual arrangement, but many others are applying the principle. One maroquinière, or leather worker, for Louis Vuitton changed careers a decade ago, from making computer chips to making handbags like the Noé (originally designed to hold a few bottles of champagne). Now Sandrine (who didn’t want to provide her surname) has sufficiently mastered the 10 or 12 skills she needs to make the Noé and other luggage that she can teach them to newcomers to the maison. “It’s on me to transmit the values and methods of the house as they were taught to me,” she tells me. “You couldn’t learn it anywhere else.”

This inimitability of this level of skill is even more pronounced among Paris’s jewelry makers. During my visit to the Haute Ecole de Joaillerie, in a building on Rue du Louvre constructed in 1919 to house the industry association, steps from Place Vendôme, where the jewelers still maintain their boutiques, I watched students on one side of a wall working with files, pincers, torches, needlenose pliers, wooden hammers, hand saws, and other materiel of the industrial age, while on the other, students on a different track worked with computers to model designs in 3D to see how their conceptions would be realized. But even after they complete 3,500 hours of training over three years, many will still need to learn methods unique to the firms where they end up working. “Van Cleef, Cartier—they all have their own secret techniques,” says Ombeline Henry, director of professional training at the school. “So the training continues.” Despite the additional investment necessary, she says, all the houses are eager for new experts from the school. “All the brands have problems recruiting people,” she says. In response, the Haute Ecole is expanding, from 450 students three years ago to 650 today, to potentially as many as 1,000 in a few years. Four hundred applicants compete each year for 150 spots.

This is the magic of Paris. Craftsmanship still matters here, and it supports—through the luxury houses, the patronage of those who visit from around the world, and public efforts—a network of artists creating and restoring the luxury goods that are inextricably linked in our collective consciousness to the city itself.

Still, some of Paris’s artisans believe more could be done. Glassblower Jeremy Maxwell Wintrebert’s studio occupies three spaces in the Viaduc des Arts, a mile-long converted railway arch in the 12th that houses more than 40 ateliers. Wintrebert’s is between those of a furniture restorer and a maker of musical instruments. He points out that after the socialist government of the 1980s redeveloped the decaying infrastructure, support leveled off. Rents are slightly lower here than in the rest of the city, but they aren’t officially subsidized, and the residents’ wares are taxed at the same rate as any item of mass consumption (paintings receive a 75 percent discount). “It’s just an economy like any other, where you have to fight,” he tells me. “People are basically getting paid in social cachet. I mean, all my friends are craftspeople, and none of them live in apartments in the Marais.”

One of those friends, an employee of Wintrebert’s, has a somewhat less jaded perspective. As I watch him and two colleagues create a pyramidal piece of glass that will form part of a light fixture that is strictly “price on request”, he says that in Paris “arts and crafts are respected and valued here far higher than in other places. Which is why I’m here.”

This story appears in the Summer 2024 issue of Town & Country.

You Might Also Like