Michael J. Fox Didn’t Get Mad, He Got Motivated

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A couple of years ago, Davis Guggenheim experienced a confounding emotion familiar to anyone who spends time with Michael J. Fox. The director was in Fox’s Central Park West apartment, midway through his first day of interviewing the now 62-year-old actor and philanthropist for the 2023 biographical documentary Still.

Fox, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 1991, is not physically well, though he’s lucky to be alive, having survived 33 years with an incurable degenerative disease that kills most patients within 20 years of diagnosis. In order to speak clearly, Fox takes pills to combat paralysis of facial muscles. The more the disease advances, the more medicine it takes to animate the muscles, until the inevitable point when the side effects outweigh the benefits of the medication, or it stops working altogether. One of the worst side effects of Fox’s medication is dyskinesia—involuntary movements and tics. So, while the constant bobbing and careering may appear distressing for Fox, it is in fact the best version of himself available. He regularly acknowledges that he’s long into the journey he once referred to as the “gradual paring away of my physical self.” And yet, after listening to Fox explain his outlook on the world, Guggenheim had a realization that he had encountered a man who had achieved a spiritual state known to few. He felt the need to confess. “I want what you have,” Guggenheim told Fox.

Soon the director called for a break. “I walked 30 blocks to my hotel,” Guggenheim recalls, “and the whole time I was like, ‘Why do I feel this way? He’s got this really tough diagnosis. I don’t. But he has something that I wish I had.’ ” Fox recalls his rejoinder. “I told him, ‘Be careful what you wish for.’ ” Still, Fox understands what Guggenheim was getting at. “It’s very complicated,” he says. “I’ve said Parkinson’s is a gift. It’s the gift that keeps on taking, but it has changed my life in so many positive ways.”

Fox used to be a well-liked and funny TV and film star, a master pratfaller and teller of witty stories on talk show couches—a virtuoso of a light art. In the last 20 years he has evolved into something deeper: a philosopher, an exemplar of courage, and the exceedingly rare figure in this polarized moment that a country can unite behind. In a recent CBC TV profile, the journalist Harry Forestell, who was himself diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2015, characterized Fox’s example using words only a fellow Parkinson’s patient could, calling Fox’s public reckoning with the disease “both futile and deeply inspiring.” He is not only an inspiration to Parkinson’s patients through his public appearances and the candor of his four moving memoirs, he’s also the co-founder of the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, which in its 23 years has funded nearly $2 billion in research. He inspires not only his fans but his intimates. “They describe some people when playing a great sport as poetry in motion,” says the novelist Harlan Coben, a close friend of more than a decade. “Mike’s bravery in motion.”

Few would have predicted this trajectory. After winning a couple of acting credits as a kid, Fox dropped out of high school in Burnaby, British Columbia, at 17 and drove to Hollywood. There were a couple of lean years spent landlord-ducking and dumpster-diving before Fox landed Family Ties in 1982, which begat Back to the Future three years later. Untold fame and riches arrived overnight. During his go-go ’80s run, he was by his own admission a conspicuous consumer, a luxury automobile collector who recalls being able to light a cigarette in his Ferrari going 100 mph. “I’m sure that if you talked to him when he decided to drop out of high school, move to Hollywood, and become a movie star, that he had no intention of doing anything other than making money and being famous,” Guggenheim says. “He didn’t say, ‘I’m going to make money, be famous, and inspire people.’”

Parkinson’s didn’t change Fox overnight. When he was diagnosed at 29, a doctor told him he probably had a decade before the symptoms would end his career. And by that point, as Fox admits in his 2002 book Lucky Man, his movie career was foundering. The Back to the Future franchise was over, and he’d made a series of box office flops like Doc Hollywood and For Love or Money. The diagnosis sometimes felt like the karmic price for his success, “the bill being brought to a sloppy table after an ill-deserved and underappreciated banquet,” as he wrote.

Fox hid his Parkinson’s, collected checks for movies that felt beneath his talents, and hit the pillow hammered every night. Predictably, a breakdown followed. He went to his first AA meeting and got sober. He found a Jungian analyst named Joyce and confessed that he felt as if his life were “in flames.” Today he recalls the moment in the mid-’90s when he experienced an epiphany on Joyce’s couch. “My therapist said, ‘How are you feeling?’ ” he recalls. “I said, ‘I’m just waiting for the other shoe to drop.’ And she said, ‘Michael, you have Parkinson’s! The other shoe dropped a long time ago.’ ”

Difficult days, Fox understood, lay ahead. There was no better option than to surrender to appreciating the gifts of the present day. His taxonomy of what mattered and what didn’t was turned on its head. Family landed on top. Fox and his wife, the actress Tracy Pollan, had been married only three years before his diagnosis. Divorce following a Parkinson’s diagnosis is common, yet Pollan stuck around.

“Everybody says ‘in sickness and in health,’ but sometimes it’s not that easy,” says the couple’s friend Cam Neely, the former hockey star and longtime president of the Boston Bruins. “Everybody thinks about what Mike goes through, but one can only imagine what Tracy goes through. You can just tell how much she loves him, but one thing about Tracy, she’s a strong, tough woman, and doesn’t put up with any BS.” Fox had one request before he would allow Guggenheim to make a film about him. “No violins,” he said, meaning no treacly music scoring scenes of his physical struggles. And Fox offered only one note after screening a rough cut of Still: “More family.” Still’s most affecting scenes are those of Fox collapsing in joyful laughter when Pollan or one of his four kids ribs him.

Fox kept his Parkinson’s a secret until 1998, when he made an announcement to Barbara Walters and People. It was made under duress: The National Enquirer was close to breaking the story of the health issue that was affecting the schedule of Fox’s sitcom, Spin City. Despite the circumstances, the unburdening brought unexpected joy—and then an idea. “When I went public, I felt like I stood there naked in the town square and said, ‘Look at me. This is what it is,’ ” he says. “What I didn’t realize was how many other people had been dying to do that.”

Overnight, various Parkinson’s foundations clamored to land Fox as their spokesman. “Early on someone from a foundation gave me their pitch as to why I should come on,” he says. Fox politely demurred, saying he appreciated the group’s efforts. “But then they said the most unusual thing,” he recalls. “They said, ‘But if you don’t help us, don’t help them,’ pointing to another foundation. I got so mad. I said, ‘I’ve got to get in here and get this straightened out.’”

In 2000 he founded the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research with the goal of funneling money to scientists with the best shot of finding a cure. The monumental ambition of the mission didn’t just occur to him. “It seemed straightforward to me,” he says. “I’m a short kid from Canada who at 17 moved to another country and somehow within five years was a millionaire. I’m of the mind that anything you want to do you can do.” He went on a listening tour of scientists, politicians, and patient advocates. His conclusion: Foundations were mostly covering the unmet needs of patients while also lobbying the government to fund research. But despite these efforts the government wasn’t coughing up enough money to make sufficient advances. “The science was ahead of the money,” he says. “We just have to throw the money at the right people.”

To find a CEO for his foundation, Fox met with candidate after highly qualified candidate from the nonprofit world, but he decided he wanted something different, someone who could innovate like a startup founder. After spending nine years making other people money at Goldman Sachs, Deborah Brooks was looking to do some good. “I thought, Wouldn’t it be amazing if nonprofits were more efficient, if they were bolder?” Brooks tells me. Fox hired her after one meeting; she’s both co-founder and CEO.

The pair agreed on a revolutionary fiscal philosophy. While many foundations rely on an endowment model, amassing a nest egg designed to assure long-term survival by parceling out small percentages to recipients, Fox’s foundation would attempt to go broke annually. “The goal is to go out of business,” Fox has said. In 2020 the foundation brought in $199 million in private donations and the next year funded $233 million in grants. According to Brooks, after spending nearly $2 billion on research, the foundation in 2022 had allocated more on Parkinson’s research than the U.S. government—and it seems to be paying off. In April, Lancet Neurology published the results of a decadelong Fox foundation–led study demonstrating that Parkinson’s can now be detected in living people by locating a particular biomarker protein, abnormal alpha-synuclein, a discovery that has the potential to lead to a treatment that can delay, or even eliminate altogether, the onset of symptoms. “When I was diagnosed, it was like a drunk driving test,” Fox says. “Now we can say, ‘You have this protein, and we know that you have Parkinson’s.’ It opens the gates for pharmaceutical companies to come in and say, ‘We’ve got a target and we’re going to dump money into it,’ and when they dump money into it, good things happen.”

For many years the ability to turn lemons into lemonade was Fox’s brand. His 2009 memoir, Always Looking Up, was subtitled The Adventures of an Incurable Optimist. In 2018, when a spinal tumor unrelated to his Parkinson’s threatened to paralyze him, he opted for surgery that required months of physical therapy to get him walking again. Freshly rehabilitated and finally on two feet, on a rare night alone in his apartment he tripped and did a header in the kitchen, breaking his upper arm. Fox recalls the words that he uttered while splayed on his floor: “I said, ‘Fuck lemonade. I’m out of the lemonade business.’ ” He chronicled his medical misadventures and attendant depression two years later in his book No Time Like the Future. “That was nothing,” he says now. He has since broken his other arm and shoulder, smashed his orbital bone and cheek, and broken his hand. “My hand got infected and then I almost lost it,” he says. “It was a tsunami of misfortune.”

But Fox is smiling. There’s no self-pity in the litany, more pride in showing off battle scars. He often refers to himself as a “tough son of a bitch,” a trait reflected by his daily training to remain ambulatory, despite the damage he faces from his now daily falls. I ask if anything scares him, and he thinks for a moment. “Anything that would put my family in jeopardy,” he says. He has nightmares about falling into Tracy or one of the kids on the street, and them getting hit by a bus. But fear for himself, the future, the ultimate other shoe dropping? Not so much.

“One day I’ll run out of gas,” he says. “One day I’ll just say, ‘It’s not going to happen. I’m not going out today.’ If that comes, I’ll allow myself that. I’m 62 years old. Certainly, if I were to pass away tomorrow, it would be premature, but it wouldn’t be unheard of. And so, no, I don’t fear that.”

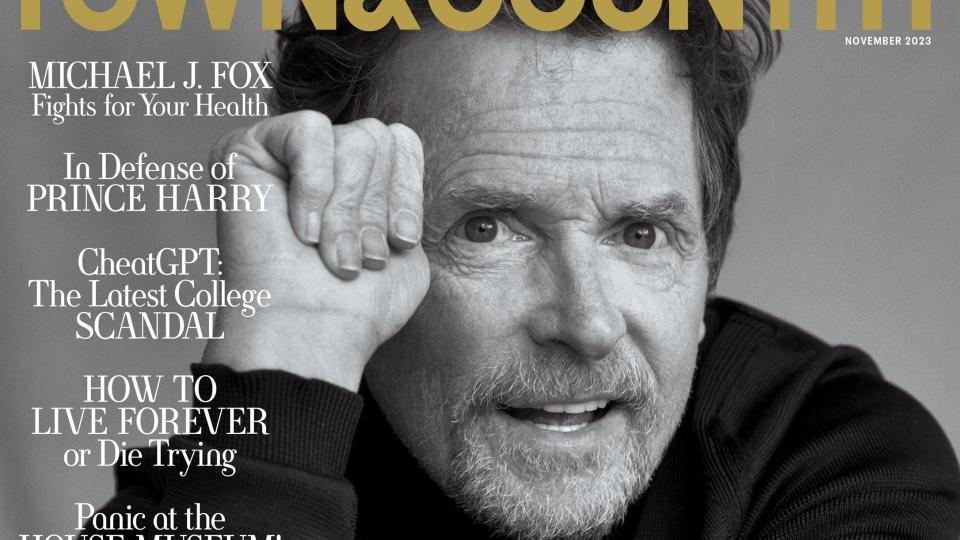

Photography by Sebastian Kim. Styled By Britt McCamey. Grooming by Kristan Serafino at Walter Schupfer Management. Shot at Corner Studio NYC. Production by Area1202. Table by Kristina Dam

In the photograph at the top of this story: Brioni sweater; Breguet watch ($18,000)

This story appears in the November 2023 issue of Town & Country.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like