The quest for Lake Superior shipwrecks

PARADISE — Nobody knows exactly how many shipwrecks lie beneath the waters of the Great Lakes. While some wrecks are known and documented, many others are still waiting to be discovered and for their stories to be told.

The Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society is committed to telling those stories.

The nonprofit Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society (GLSHS) is responsible for many recent shipwreck discoveries in Lake Superior. The organization got its start in 1978 when Tom Farnquist and a group of divers, teachers and educators recognized the need to discover, document and preserve the history of Lake Superior shipwrecks and the lighthouses that tried to prevent them.

“Our mission is to preserve the lights and stations that warned mariners and to honor those who perished in shipwrecks,” said Bruce Lynn, executive director for GLSHS. “And, as our name implies, we have it as our mission the discovery, documentation and interpretation of shipwrecked vessels.”

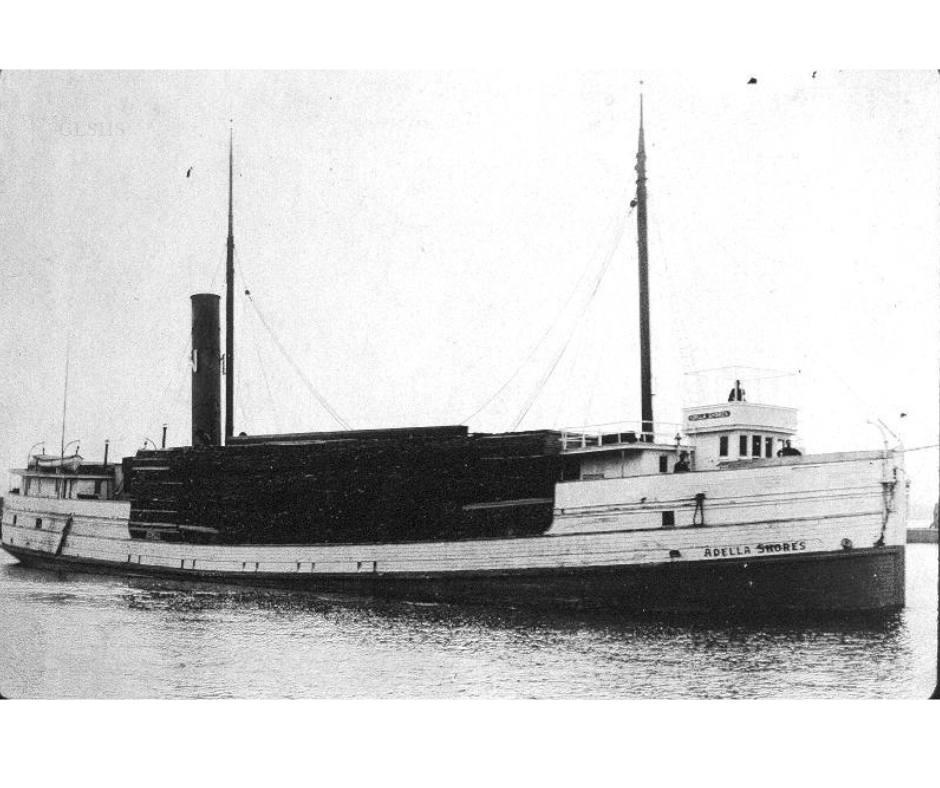

More: Lake Superior shipwreck Adella Shores, missing since 1909, finally found

More: ‘Four days of hell’: Remembering the 1913 storm that sunk a dozen Great Lakes ships

The Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum at Whitefish Point in the eastern Upper Peninsula is home to the oldest operating lighthouse on Lake Superior. Its light has shone since 1861, the same year Abraham Lincoln became president. The museum has become one of Michigan’s most popular tourism attractions, recording over 100,000 visitors annually. The museum offers a variety of displays, from the famous lighthouse to a 1940s-era lifeboat to the restored lighthouse keeper’s quarters to the 200-pound bronze bell of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

“Our operation is unique because we’re one of the only museums that also has an expedition and discovery arm,” said Lynn. “We have our bases at the Whitefish Point museum and at our office in Sault Ste. Marie, but we also have a crew of researchers and analysts who study, look for, find and document shipwrecks. That means we are literally growing and developing the history that we display to the world, because a significant aspect of our operation involves finding shipwrecks and solving the mysteries that enshroud them.”

Lynn, who’s led GLSHS as executive director since 2011 when Farnquist passed the torch, said public interest in shipwrecks and the museum’s work to document them has soared. According to Lynn, people understand that shipwrecks are a part of human history. Every shipwreck has a story to tell about what life was like during various periods of human activity in the Great Lakes region. Yet, that story cannot be fully told until the shipwrecks are found and the mysteries surrounding their disappearance are solved.

The public undoubtedly agrees with that sentiment. From National Geographic to the Discovery Channel and the Travel Channel, GLSHS has earned national acclaim for its wide array of works in preserving, documenting and interpreting maritime history in the Great Lakes.

More: After 100 years, shipwreck hunters find steel freighter Huronton at bottom of Lake Superior

Subscribe: Check out our offers and read the local news that matters to you

But how does the organization go about finding a shipwrecked vessel?

According to Lynn, a combination of technology, research, weather, patience and sheer luck determine whether or not the GLSHS crew and their partners find a shipwreck.

“An expedition usually begins during winter,” said Lynn. “Our top researcher and director of marine operations Darryl Ertel and our support staff begin by studying documentation, evidence and other primary source material about a ship that was known to disappear in some area of the lake during a certain period of time.”

Lynn describes hours spent in local libraries, poring over microfiche, reading history books and talking to locals and experts near and far.

“The initial research is what clues us in on roughly whereabouts a shipwrecked vessel may be,” said Lynn. “Then Darryl starts drawing up a grid of potential search areas for us to explore.”

It’s not always just a matter of research in the winter and fieldwork in the summer to find a shipwreck. Sometimes, the research side takes months or even years, particularly if there were no survivors from a wreck who would have been interviewed by journalists and could have provided information that today could be used to pinpoint the shipwreck’s location. Shipwrecks like the SS Western Reserve (lost in 1892), the SS D.M. Clemson (lost in 1908), and a pair of World War I-era French minesweepers (the Inkerman and the Cerisoles, both lost in 1918) are just a few examples of Lake Superior shipwrecks that continue to evade searchers to this day.

But when enough clues add up, it’s time to shift from research to exploration.

“When we have a rough idea of where a shipwreck is, we’ll assemble our crew on the GLSHS research vessel the R.V. David Boyd, and head out,” said Lynn.

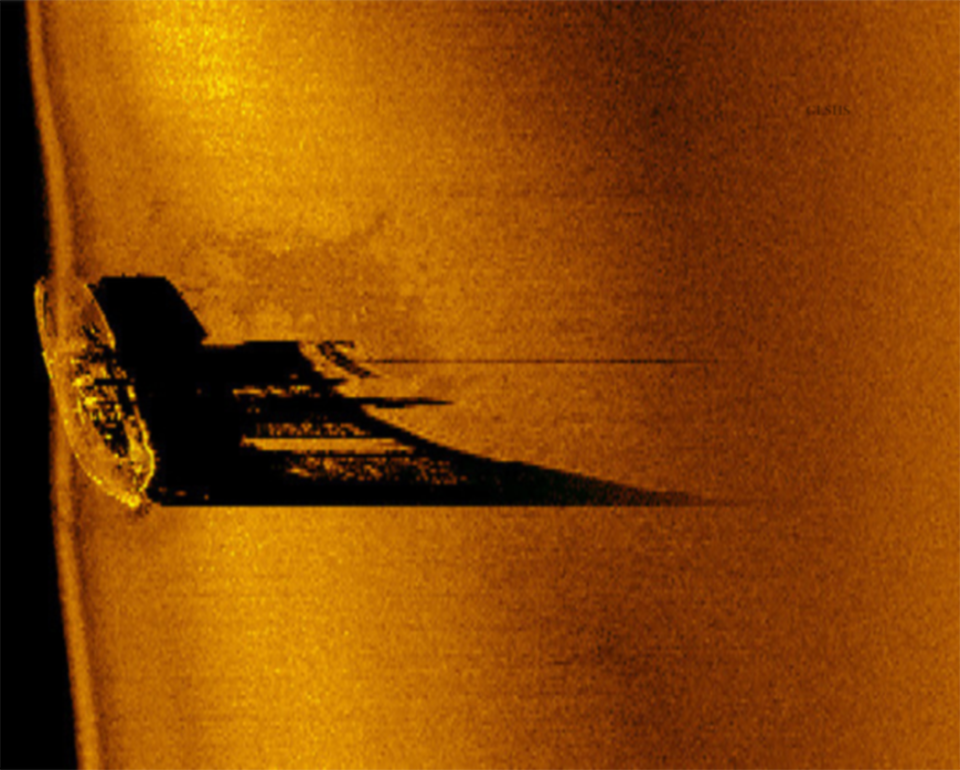

Once in the perceived general vicinity of a shipwreck, the team deploys their side-scan sonar system, which was sourced from a company called Marine Sonic Technology in Yorktown, Virginia that became interested in GLSHS’s work, in a grid-like search pattern called “towing” to search for the wreck.

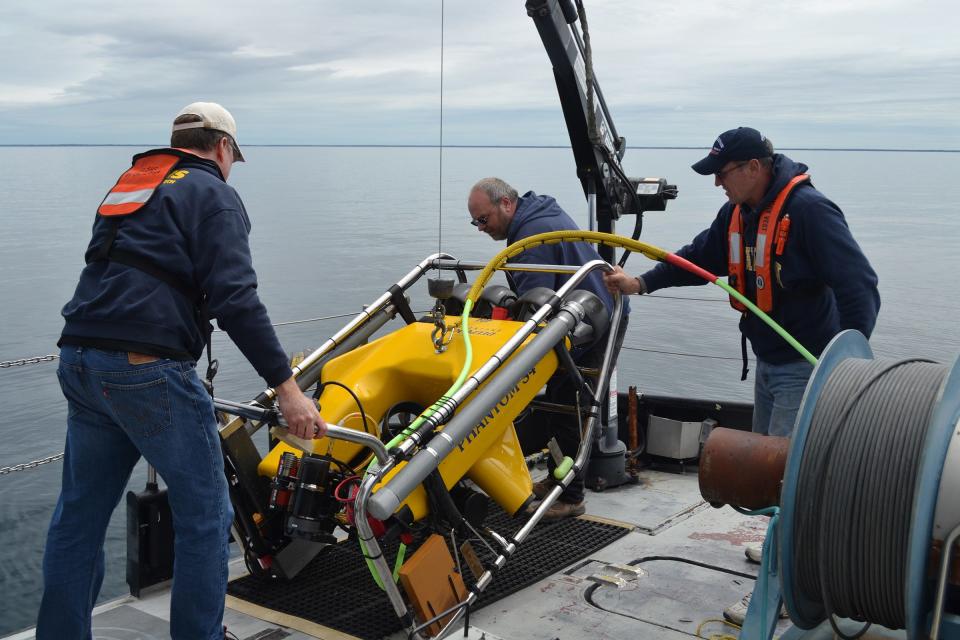

If and when the sonar finds an anomaly on the lakebed, the crew launches its Remote Operated Vehicle (ROV), which can descend over 1,000 feet into the lake. The team’s ROV uses a “crabbing” movement pattern to scan for shipwrecks, and once a wreck is found, the ROV is moved alongside the wreck. The researchers use photos and video taken from the ROV to measure the ship, identify its markers and gather other essential data needed to confirm the wreck.

Back at the base, information gathered from the ROV is compared to primary source material, and the researchers compile evidence showing the wreck they’ve found matches the specs of the ship that disappeared in that area.

Once Lynn’s team confirms the find, Lynn puts out press releases announcing the find, and the team shifts to the next project stage: documentation.

“We’re historians at heart, so the last leg of our journey in finding a shipwreck involves writing articles about the find, setting up exhibits, creating documentaries detailing the history of that ship and how it wrecked, and speaking with the descendants of sailors who lost their lives in the wreck,” said Lynn. “Our goal is to solve the mysteries of the deep, so getting the information we uncover compiled and published is a big part of what we do.”

More: Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society discovers 1879 shipwreck

More: Shipwreck society announces new WWII era find in Lake Superior

The step-by-step process of an expedition may sound straightforward, but Lynn emphasized that it rarely goes that smoothly in practice.

“We’re often held up by bad weather,” he said. “Our ROV is an excellent little machine, but it’s 28 years old. Our research vessel is like any other boat and requires repairs and maintenance. Our research and study of primary source material sometimes doesn’t furnish results, and we’ll be on the water searching grids for hours without finding anything.”

But when the team does find a shipwreck that’s been lost to humankind for decades, Lynn said the thrill of the find is worth the effort needed to arrive at that point.

In addition to good weather, tech that works and accurate primary source material, Lynn said the human resources invested in each expedition are undoubtedly the most important factor in finding a wreck.

“Everything we do as an organization revolves around teamwork,” he said. “That goes for our operations at Whitefish Point, in Sault Ste. Marie, and when we’re on the water aboard the David Boyd.”

Lynn noted Dan Fountain, who recently helped GLSHS find the wreck of the Arlington, brothers Darryl and Dan Ertel, Sarah Wilde, Ric Mixter, Corey Adkins and others who have helped find shipwrecks.

Lynn also commended the local community for their support of the group's work.

“There is undoubtedly a direct correlation between the increase in support from the community and the team’s ability to find shipwrecks,” he said. “The community is invested in finding these wrecks, so they support us however they can. Some contribute to our nonprofit, others volunteer, some send us primary source material and others become annual donors.”

For more information about the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society, visit shipwreckmuseum.com.

Ren Brabenec is a Brimley-based freelance writer and journalist with The Sault News. He reports on politics, local issues, environmental stories, and the economy. For questions, comments, or to suggest a story, email hello@renbrabenec.com.

This article originally appeared on The Petoskey News-Review: The Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society and its quest for Lake Superior shipwrecks