I was an adult before I learned of Michigan Central Station's ties to Black history | Opinion

It was June 1977, and 30 or so children had gathered at the entrance of the Michigan Central Station.

I was one of them.

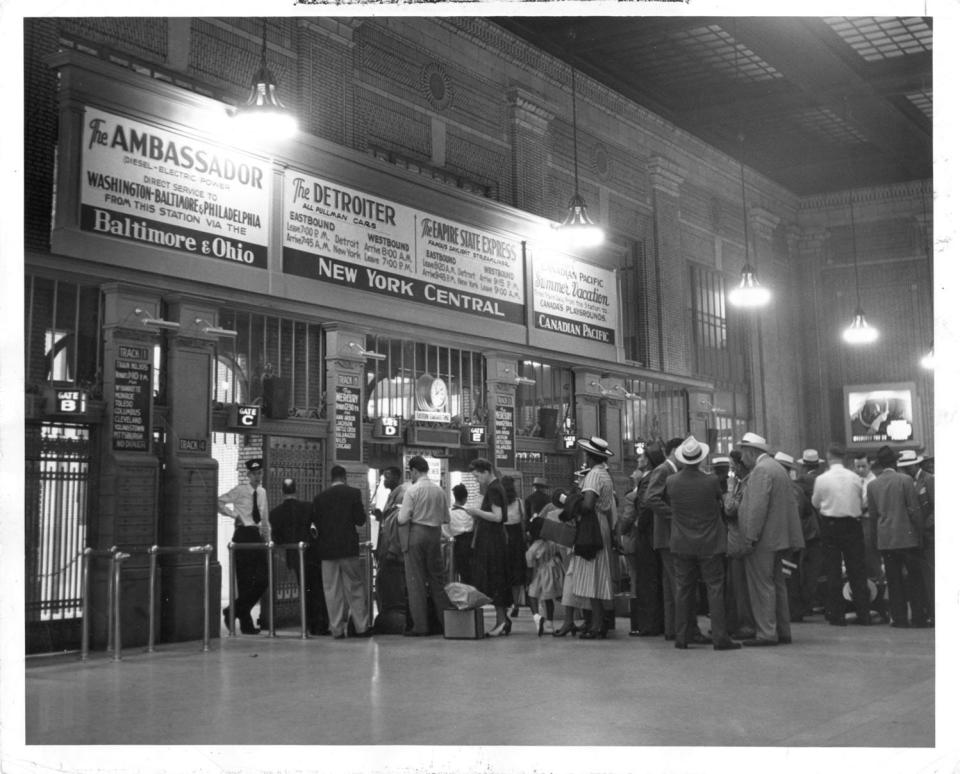

As we entered, the wide-open space of the lobby was overwhelming to the group of 4-, 5- and 6-year-olds. Most of the shops were not open or operating, but the popcorn vendor was still there, and there was always the strong smell of popcorn.

In 1988, the train station closed. After years of sitting empty, it will reopen on June 6. Many of us assumed it would never reopen. All it seemed good for was being used as the backdrop for disaster films, where it would get destroyed by large robots or superpowered aliens. I took the train from Detroit to Kalamazoo a few times when I was in college, boarding at a sad little trailer next to the once-majestic Michigan Central. I was always thinking about those trips in 1977, when I was 6 years old. Inside the station, we were placed in lines by the teachers and chaperones from Little Angels’ Nursery & Kindergarten, our Highland Park preschool. Once the train arrived, we boarded it in order, seated in pairs, near an adult.

We were on our way to Ann Arbor to visit the University of Michigan Museum of Natural History. We took this trip every year.

And every year, I bought at least one of the rubber dinosaur figures from the gift shop — a triceratops one year, a T. rex or stegosaurus the next.

We had lunch and played video games at Pinball Pete’s, and then we came back to Detroit.

But the whole day would start and end at the Michigan Central Station, and it was as much a part of the field trip experience as the train trip, the museum and the arcade.

Even as a preschooler, I was taught that the dinosaurs we saw at the museum lived long before us, and the significance of their impact on the world.

But it would not be until I was near adulthood that I learned how important the history of the Michigan Central Station was to Detroit.

And to me.

Is the Michigan Central Station part of your family's history? Tell us at freep.com/letters, with "train station story" in the subject line.

Boomtown Detroit

In 1825, Detroit was becoming a boomtown.

The Erie Canal opened, and shortly after, thousands of people began moving either to Detroit from New England, or through Detroit on their way to Chicago. In 1831, the Detroit & St. Joseph Railroad was chartered as a new railroad company, with plans to connect Detroit to the west Michigan city of St. Joseph. By 1846, the company was operating as the Michigan Central Railroad, owned by John Murray Forbes and James Frederick Joy. By 1852, the new owners had completed the connection from Detroit to Chicago. John Murray Forbes, a staunch abolitionist in the mid-1800s, was an ancestor of former U.S. Sen. and former Secretary of State John F. Kerry. The “F” in Kerry’s name is “Forbes.”

James F. Joy is the namesake of Joy Road — the street that runs from Detroit to the city of Dexter.

When the Michigan Central Railroad began operating in Detroit, it was immediately part of another railroad system.

The Underground Railroad.

More: Woodworker spent nearly a year re-creating Michigan Central Station lobby clock

The road to freedom

The Underground Railroad was not really a railroad.

Except when it was.

In 1844, after learning their oldest child was going to be sold away, Adam and Sarah Crosswhite escaped from slavery with all four of their children. Assisted by Quakers and other abolitionists, the family eventually settled in Marshall, Michigan.

In 1847, bounty hunters, assisted by the county sheriff, came to the Crosswhites’ home to return them to slavery, but a crowd of African American and white townspeople prevented them from doing so. The Crosswhites were whisked away to Jackson, Michigan, and placed on the Michigan Central Railroad, heading to the Michigan Central Station, then located on Third Street and Woodbridge — today, that’s the West Riverfront Station of the Detroit People Mover.

The Crosswhites would get on a ferry to Canada, and safety.

A little over a decade after the Crosswhite Affair, in January 1859, 11 freedom seekers — one of whom was pregnant — escaped from slavery after radical abolitionist John Brown raided the farm where they were enslaved.

Brown acted as a conductor on the Underground Railroad, taking the group to Chicago, where Allan Pinkerton assisted them by securing fares on the Michigan Central Railroad to Detroit, where they met Detroit Underground Railroad agents.

There were now 12 of them. The pregnant woman had given birth.

Pinkerton would one day become famous as a detective in the American West.

John Brown would meet abolitionist orator and author Frederick Douglass in Detroit, and become famous for his raid at Harper’s Ferry later that year.

Historic photos of Michigan Central Station show heyday of old Detroit train depot

The new train station

In 1866, an African American engineer began working for the Michigan Central Railroad. Born in Ontario, Canada, in 1844 to parents who escaped on the Underground Railroad, Elijah McCoy was trained in Scotland as an engineer.

When he came back to the U.S., due to racial discrimination, this trained engineer was allowed only to be a lubricator and fireman on the railroad. He oiled the metal moving parts on the train, and shoveled coal into the locomotive’s furnace.

Elijah McCoy would invent an automatic lubricator that could oil the train’s moving parts as it was moving, eliminating the need for trains to make frequent stops.

This revolutionized the railroad industry.

In 1884, a new and larger Michigan Central Railroad depot was built at Third and West Jefferson, not far from the former site of Joe Louis Arena. In 1913, that station was destroyed by fire.

The new Michigan Central Station, at 14th and Michigan, was almost complete, and opened after the fire shut the old station down.

It would become the main station for people coming to Detroit seeking employment and other opportunities during the auto industry boom.

And it as the major entry point for the African American Great Migration.

Eminem-produced Michigan Central concert in Detroit to star Diana Ross, Jack White, more

A different kind of traveler

In those first years of the brand new Michigan Central Station, many African Americans were coming to Detroit, drawn by Henry Ford's offer of $5 a day in 1914. That same year, World War I broke out in Europe.When the U.S. entered the war in 1916, many factory workers enlisted. In 1917, the Selective Service Act went into effect, and many more workers were drafted into the military.

They may have come to Detroit on the trains to achieve better lives and opportunities than what they had in the Jim Crow South, but now they were leaving Detroit on those same trains to go to military bases, that were located, in many cases, right back in the Jim Crow South.

They were going to fight for freedom and for democracy. But the nation that was sending them to fight had done a poor job of ensuring that they received it here.

Welcome to Detroit

Ossian Sweet began his journey to Detroit in the summer of 1910, working as a dishwasher on Bob-Lo island, to help pay his way through Wilberforce College in Ohio.

In 1921, Sweet had earned his degree from Howard University Medical School, and moved to Detroit, arriving at the relatively new Michigan Central Train Station. The shops would have been open, and the lobby busy with people coming and going.

Within five years, Dr. Sweet and his family would become embroiled in a civil rights case that would change Detroit forever after they used firearms to defend themselves as an angry white mob attacked Sweet’s home. Sweet, his brothers, wife and friends were charged with murder. The charges were ultimately dismissed.

While the Sweet trials were being fought in the courtroom, the Ku Klux Klan was flexing its muscles in the political arena — running Charles Bowles as a write-in Detroit mayoral candidate and lobbying the Michigan Legislature to pass a firearms registration law that they hoped would target African Americans who defended their homes with guns, like Dr. Sweet.

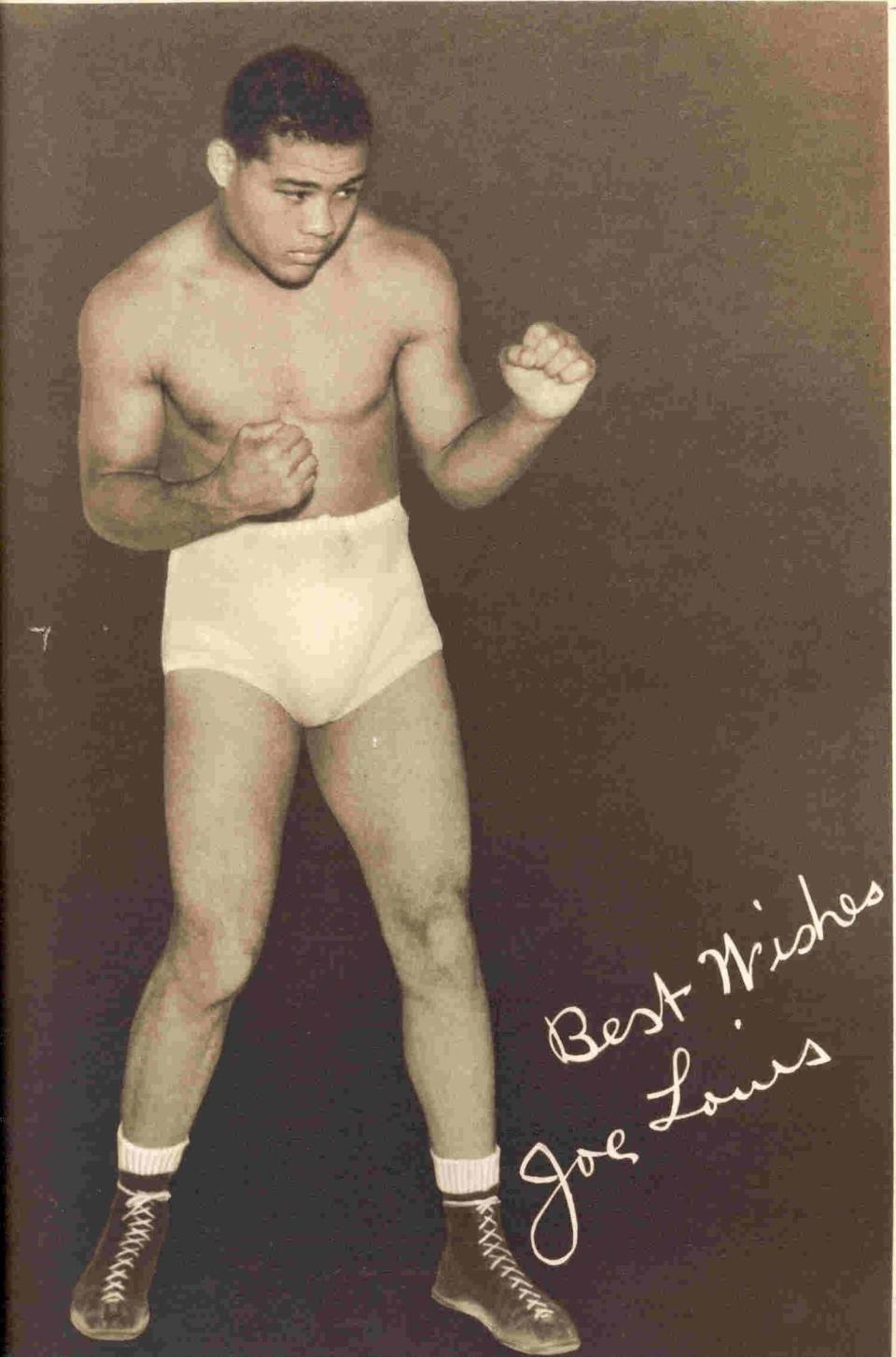

But the KKK wasn’t silent in the South by any means. In Alabama, a gang of KKK members confronted Patrick Brooks and his wife, Lillie Barrow. Brooks, his wife and their children left Alabama on a train to Chicago.

From Chicago, they got on the Michigan Central Railroad to Detroit.

And arrived at Michigan Central Station.

The beautiful lobby, with the 55-foot ceilings in the Beaux Arts style, was a powerful welcome to Detroit.

And there were no “Colored” and “White” signs, either.

One of the children of Lillie Barrow — and Pat Brooks’ stepson — was a 12-year-old named Joseph Louis Barrow.

You know him as Joe Louis.

Like many African Americans who came to Detroit during the Great Migration, the family lived in Black Bottom. Joe Louis would grow up to become heavyweight boxing champion of the world from 1937 to 1949.

One more Detroit story

In 1938, another Alabamian would come to Detroit, arriving at the Michigan Central Station.

She was born and raised in Bessemer, Alabama, and after high school graduation, was ready to leave the Jim Crow South.

She came to Detroit.

Her name was Lucinda Ruffin.

She met and married another Alabamian she met in Detroit, Moses Ross.

She met him through his cousin, Iredia Vasser, a beautician, who was Lucinda’s best friend and fellow congregant at Chapel Hill Missionary Baptist Church on Joy Road and Grand River on Detroit’s west side.

Lucinda Ruffin, who arrived to Detroit at the Michigan Central Train Station (she never learned how to drive a car), and Moses Ross had one child — Jacquelynne Iredia Ross.

Jacquelynne Iredia Ross married a young man whose family came from Macon, Georgia, and who himself grew up in Black Bottom before it was demolished.

His name was James Michael Jordan Jr.

Jacquelynne and James had two children together — James Michael Jordan III and Jamon Jordan.

Me.

The trip I’m dreaming about

Within four years of being born, I was enrolled at Little Angels’ Nursery School, where I would take my first trip on a train. And by the time I was 6 years old, I was well-versed on not only the train, but the Michigan Central Station, the lobby, the ceiling, the people coming in and out, the ticket booth.

And the popcorn.

In 1988, the station closed.

Throughout the '90s and early 2000s, there were plans to do something with the building, including turning it into the Detroit Police Headquarters or a casino. More than once, it was threatened with demolition.

But in 2017, Detroit Homecoming was held there. The event invited former Detroiters back to celebrate their hometown.

A year later, in May 2018, the building, along with the Albert Kahn-designed Roosevelt Warehouse (also known as the Detroit Public Schools Book Depository) was sold to Ford Motor Co.

Ford announced that the site would be the center for the company’s autonomous vehicle production, and led the creation of Michigan Central, a hub for technology and innovation, now housed in the former book depository building.

Newlab, a partner in the development, leads the mobility hub, and this is also where the uber-popular Black Tech Saturdays events have taken place.

The city of Detroit and the state of Michigan are partners in the project, and one of the roads in the area is the first electric charging road in the country. You can charge your electric car while driving.

The grand opening is June 6, six years after Ford bought the site. There will a concert, tours and other events at the celebration.

Folks will come from all over to see this majestic building restored and reopened.

Like so many people who either came to Detroit via the Michigan Central Station, or have heard the stories from their parents and grandparents, it is not only a National Historic Landmark.

I know that it holds the stories of people coming here from the East Coast, of escaping the Jim Crow South, and, in its earlier manifestations, escaping slavery.

And bringing families together.

So, I’ll be at the opening thinking not only of what the building is now, but all the history it holds — including my family’s.

But, I’ll also be thinking that maybe, just maybe, one day I’ll be able to get on a train there again, and go to Ann Arbor and buy me a rubber triceratops from the U-M Museum of Natural History.

And I’ll be thinking about that popcorn smell.

Jamon Jordan was hired as the city of Detroit's first official historian in 2021. He is also the founder of the Black Scroll Network History & Tours, and teaches a class on Detroit history at the University of Michigan.

Tell us your story

Is the Michigan Central Station part of your family's history? We're eager to hear your stories. Send us a letter to the editor at freep.com/letters with "train station memories" in the subject line, and we may publish your story online and in print. Be sure to let us know if you have pictures of the train station from days of yore. We ask for letter writers' email addresses, home addresses and daytime phone numbers for verification purposes only; that information won't be published.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: As Michigan Central Station re-opens, remember Black Detroiters