How America’s Rich Legacy of Fear and Hatred Fuels the Conspiracy Theories of Today

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This article was adapted from The Politics of Fear: The Peculiar Persistence of American Paranoia. It appears at TPM by arrangement with Vintage Books, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

If America’s paranoid style is homegrown and unique, conspiracy theory is universal. By the early 1920s, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion — the Beethoven’s Ninth of conspiracy theory — had been translated into German, Polish, French, Italian, and English. Its first Arab translation appeared in 1925, and it was published in Portuguese and Spanish in 1930. Even after some of its German readers acted on its lessons and exterminated millions of Jewish men, women, and children, it continues to be read and studied around the world. It is explicitly cited in Hamas’s charter and was the basis of TV miniseries in Egypt and Syria and several documentaries in Iran. But, as deplorable as it is that the Protocols would have the propagandistic currency that it does in the Middle East, it’s not surprising, as the Arab-Israeli conflict has been inescapable for the past three-quarters of a century and more. It’s also understandable that conspiracy theories would be as rife as they are in countries that really are groaning under nonmetaphorical tyrannies, or that did in the not-so-distant past.

But the gap between reality and the stresses that give rise to paranoid fantasies is much larger in the United States than in much of the Muslim world today. For all of America’s longstanding racial, ethnic, and religious enmities, most of its citizens — including many who claim to have been dispossessed — enjoy a relatively high standard of living, and its laws still protect the press from censorship. Unless you are poor, undocumented, incarcerated, or Black, the hand of the government lies much lighter on U.S. citizens than it does on those of many other countries.

So why here? Exactly what are America’s many conspiracy theorists so afraid of?

I covered a conference of Richard Spencer’s alt-right National Policy Institute in 2011. The last speaker I heard was the well-known white nationalist Sam Dickson, David Duke’s lawyer and a former candidate for lieutenant governor of Georgia, who described his life’s journey from youthful Goldwater activist to a true believer in the ethno-state. His words, spoken in a courtly southern drawl, left an indelible impression on me.

Movement conservatives, the Tea Party, all of them miss the point, he said. While they talk about “taking America back,” they forget that the Constitution was poisoned at its inception by “the infection of the French Enlightenment.” White people haven’t controlled America’s government for 150 years, he alleged. In fact, the constitutional republic is the white race’s greatest enemy. “Our government hates us, degrades us, and seeks to destroy us,” he said. “We cannot save America. We need to let go and think of something new. America is the God that failed.”

Dickson’s frankness, of course, is not the norm among conservatives, even if some of his sentiments are more widely shared than most care to acknowledge. Repressed desires, like the forbidden hope that America will end its experiment with democratic republicanism and replace it with an authoritarian Christian regime like Hungary’s, give rise to the same kinds of painful dissonances that irrational beliefs do. One way to manage the discomfort is to project those beliefs onto your enemies: Obama despises America. Biden is a tyrant. Democrats want Republicans dead and they have already started the killings.

As wrong as they are about everything else, the conspiracy theorists seem to be right about one thing. A great many of America’s problems share a hidden factor. The conspiracy theorists may not identify it correctly — it isn’t Jewish chicanery, satanically inspired homosexuals, or space aliens. Nor is it critical race theory or drag queens. It is racism and bigotry, whether acknowledged or unacknowledged, de jure or de facto, an active principle or a lingering vestige of a willfully misunderstood past.

The conspiracy theorists are right about something else as well: things are not always what our parents and teachers and pastors taught us to believe they are. America has often failed to live up to its exceptionalist ideals. That’s not to say that America is exceptionally wicked. As nation-states go, the United States is better than many, and its founders’ ideals are mostly admirable, even if they and we have often failed to live up to them.

But like they do in most places, America’s financial, political, and social elites really do keep a tight grip on the reins of power — that’s why they’re called elites — and they work hard to protect their interests. Despite what they tell us, what’s good for them is not always what’s good for everyone else. While it’s true that capitalism has raised living standards across the board, from a child mill worker’s perspective 150 years ago or a part-time minimum-wage worker’s today, owners continue to enjoy all kinds of unfair advantages. Does the capitalist class routinely hold secret ceremonies in which they ritually rape and murder children? Of course not. Most of their energies go into union busting and political lobbying to keep their taxes low and regulations at a minimum. The owner class constantly tests the limits of what they can get away with, and they get away with a lot.

Our great national myth — that America is a crucible of equality, tolerance, and boundless entrepreneurial opportunity — has never been our national reality. Critical race theory doesn’t explain everything (no one theory could), but it surfaces a painful and undeniable truth: that our liberal humanist traditions were not only erected on a rickety scaffolding of race supremacism, religious bigotry, land theft, involuntary servitude, and toxic masculinity, but were compromised by them from the very beginning, as surely as Sam Dickson said they were by the egalitarian values of the French Enlightenment.

Which isn’t to say that things haven’t improved — I personally believe that what Dickson diagnosed as an infectious agent was the antibody for toxins like himself, and I suspect that he knows that too. I further suspect that what has driven so many white American Protestants (Dickson also spoke about his pride in his Huguenot roots) into right-wing extremism is the realization that the implicit promise of white, Protestant, male hegemony no longer holds. That’s to our credit.

Some of the American dream is real, of course. As a second-generation Jew, I’m a beneficiary of it, as are the descendants of many of the other immigrant groups that came here voluntarily. Many Americans — including Black ones — really have pulled themselves up by their bootstraps, and for all of its many failures in practice, our system leans toward more rather than less liberty and opportunity. But America’s past, like most countries’, is not just marred by but defined by force and violence and fear and hate; worse still, as William Faulkner put it in Requiem for a Nun (a novel whose plot turned on the legacies of race and rape), “it’s not even past.”

Among the fiercest of America’s old hatreds, I would argue, is the hatred of Catholics. The first colonists brought it with them from England.

A recent archaeological find sheds new light on this. In 2013, the remains of four men were discovered at the site of a chapel in Jamestown. One of them, Captain Gabriel Archer, had been buried with a silver box that a CT scan showed contained bone fragments and a lead ampulla. It was almost certainly a Catholic reliquary, and it was, in the words of The Atlantic’s Adrienne LaFrance, “a bombshell,” potential “proof of an underground community of Catholics.” They would have had to have been secret because Catholic worship had been banned in England since 1559, when Queen Elizabeth issued the Act of Uniformity.

The English Protestants who colonized the New World feared hunger, illness, and childbirth, which killed one out of eight expectant mothers and a third of their children who were born alive by their fifth birthdays. They feared the raw wilderness and its indigenous inhabitants, who they knew were servants of the Devil, and the witches and other minions of Satan that dwelled among them, disguised as their wives, children, neighbors, servants, and enslaved people. They feared their own sinful natures and Antinomianism or “Free Grace” Protestantism, the radical doctrine that once they were saved, Christians were no longer bound by the moral law, a philosophy, they believed, that could not but lead to licentiousness and attacks on property and the political order. Most of all, they feared Catholicism, which they had been at war with since the time of Henry VIII. The Catholic French had forged alliances with native tribes in the north and west. The Catholic Spaniards controlled the south. The threat of internal subversion was real as well; the Gunpowder Plot conspirators had been executed less than a year before the Jamestown settlers departed England.

Many of those Puritans’ descendants still see the world much as their ancestors did, though their great enemy is no longer godless papists and savages but depraved liberalism, or at the conspiracy theorist extreme, some differently titled ism that in practice looks and sounds an awful lot like Catholicism. Illuminism perhaps, or “cultural Marxism.” Or Zionism, the philosophy, they believe, of an ancient, fabulously wealthy elite whose power transcends national boundaries and whose leaders invisibly bend the world to their wills using the power of propaganda and finance. The Davidic superstate of the Protocols is a fantasy, but the Vatican was and is very real. (“You know, I am not antisemitic, and I am not anti-Black; that’s a complete misunderstanding of what I am,” Tucker Carlson recently, reportedly, said. “I am anti-Catholic.”)

Practicing Catholics were explicitly banned from Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire. Roger Williams founded Rhode Island as a refuge for religious dissenters in 1636, but virtually no Catholics lived there to enjoy the privilege of freedom of worship at the time. Pennsylvania and Delaware also tolerated Catholics, but few lived in either colony until much later. Virginia expelled priests from its territory in 1641. Georgia offered freedom of worship to all “except papists.” New York banned Catholicism in 1688; New Jersey passed its first formal anti-Catholic law in 1691; in 1701, it granted liberty of conscience to all “except papists.” South Carolina enacted similar legislation in 1697 but dropped its religious test in 1790; Catholics were not allowed to hold public office in Massachusetts until 1833, in North Carolina until 1835, and in New Jersey until 1844. Maryland’s chief sponsor, Lord Baltimore, had envisioned the colony as a refuge for Catholics like himself, but it didn’t go as planned. Though the Maryland Toleration Act, which became law in 1649, granted the right of free worship for any “professing to believe in Jesus Christ,” it was overturned in the early 1650s when Puritans briefly seized control of its government. It was restored a few years later, only to be overturned again in 1692, when Catholicism was formally banned in the colony.

As Robert Emmett Curran wrote in his book Papist Devils: Catholics in British America, 1574–1783, anti-Catholicism was “an effective unifying force, both in England and in British America, in defining a society by an ‘other’ that contradicted all that that society stood for and whose very survival the ‘other,’ by its very presence, threatened.”

A number of anti-Catholic secret societies arose during the high tide of Irish Catholic immigration. The American Brotherhood (which quickly changed its name to the Order of United Americans) was founded in New York City in 1844 with a mission “to release our country from the thralldom of foreign domination.” The Order of United American Mechanics began in Philadelphia a year later, and in 1850, the Order of the Star Spangled Banner was founded in New York with the explicit goal of driving Catholic immigrants from public office and organizing boycotts against their businesses. The New York Tribune’s Horace Greeley dubbed the groups “Know Nothings” because of their oaths of secrecy, but also because of their ignorant narrowmindedness. The name caught on, and like so many other pejoratives, was adopted as an honorific by their members.

While the Know Nothings opposed so-called papism on moral grounds, they were pragmatic in practice; their chief aims were to reverse the downward pressure on wages caused by immigration and the rising corruption of the Catholic-dominated urban political machines. The owner class was more ambivalent. While they were happy to replace American workers with hungry immigrants who would work harder for less, they worried about the revolutionary spirit of 1848 sweeping Italy, Germany, and Ireland, among other countries, which some of those immigrants carried with them from abroad.

By 1855, the Know Nothings had coalesced into a full-blown political party, the American Party, which filled some of the void left by the collapse of the Whigs. “As a nation,” the former Whig Abraham Lincoln wrote to his friend Joshua Speed at the time, “we began by declaring that ‘all men are created equal.’ When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read ‘all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and catholics.’ ” Nonetheless, eight governors, more than one hundred U.S. congressmen, and the mayors of three major cities had been elected on American Party tickets by the end of the decade.

Compared to the monstrous injustice of slavery, the decades of sectional strife it caused, and the cataclysmic disasters of secession, the war, Reconstruction, and the Jim Crow era that followed, the clamor over Catholic immigration was little more than background noise. That said, as John Higham, author of the seminal study Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925, put it, the American Party provided a rare opportunity for the fraying republic to come together around a different shared hatred during the decade of Bleeding Kansas.

That hatred has had a lasting impact on American conspiracy culture. Picture this classic conspiracy theorist tableau: in a dungeon beneath a gloomy mansion, a group of immensely rich and powerful men, draped in silk robes, utter incantations in a strange tongue while sipping libations of human blood. Clouds of incense hang in the air.

Whether those celebrants are believed to be Elders of Zion, Illuminated Masons, billionaire apparatchiks of the New World Order, the elites of the QAnon believers’ imagination, or all of them working together, the image’s ur-source is Roman Catholic priests celebrating the Mass, as refracted through the distorting lenses of biblical End Times prophecies, the geopolitics of the Reformation, middle-class Americans’ resentments of the opaque and sometimes questionable practices of bankers and financiers, and, ironically, Catholicism’s own long-standing fears of Illuminism and Freemasonry.

For the Puritans, Catholics were the Romans, the ancient enemy the early Christians defined themselves in opposition to (along with the pharisaical Jews). For the Catholics, the enemy was not just the Jews who rejected Christ, but heterodox Christians who denied that the Catholic Church is the body of Christ, and the forces of Marxism, scientism, nihilism, atheism, secularism, and all of the other isms that have been eating away at the one true church’s authority and power.

Of course, real Jews and Masons, as opposed to the Jews and Masons of the conspiracy theorist imagination, don’t practice magic or worship Satan; most Jews don’t believe in the literal Devil, and while many Masons are Christians, few are superstitious. Neither drinks blood — figurative, real, or transubstantiated — in their ceremonials. But conspiracy theorists nonetheless imagine that their enemies celebrate Black Masses, because they think in Manichaean binaries — good versus evil, Christian versus Jew, Protestant versus Catholic, American versus non-American, civilization versus barbarism — and perhaps because they guiltily project the aspects of themselves that they are ashamed of onto their enemies. The Christian blood that Jews were accused of mixing into their Passover matzos, the adrenochrome that QAnon believers say the elites extract from children, is the Eucharist defiled.

Protestant conspiracy theorists look at their enemies and see Catholics. So do Catholic conspiracy theorists, at least when they are looking at the Masons, another group that captured Americans’ imaginations and attracted their hatred, animating today’s conspiracy theories. And it’s no wonder, because so many of the Masons’ secret rituals evoke their society’s fanciful connections with medieval Catholicism.

Beyond the Masons’ specific references to the Knights Templar and Jacques de Molay, the Templars’ last grand master (he was burned at the stake in 1314), the Gothic cosplay that figures in so many of their rituals is also characteristic of a lot of the Romantic art, architecture, landscape design, and literature of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The Ku Klux Klan, which recruited many of its members from Masonic lodges, also adapted Catholic rituals and robes. The capirote, the pointed hood that Spanish and Italian penitents have worn since the Inquisition, was the likely source for the headpieces the Klan riders wore in D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, and that the revived KKK then adopted (the regalia of Reconstruction-era Klansmen was less formalized).

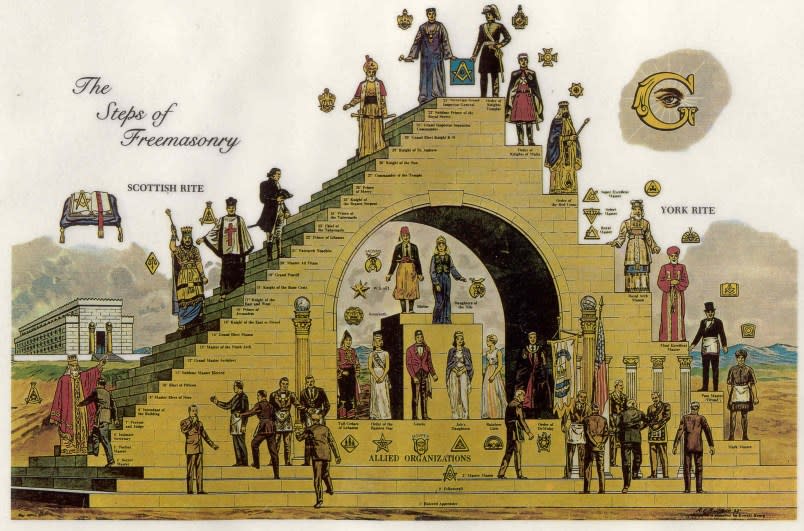

Unlike the Klan, the Freemasons were never organized around exclusion and hatred; their ideal was and is enlightenment. According to their founding myth, Hiram Abiff, the chief architect of the Temple of Solomon, was martyred when he refused to reveal the stonecutters guild’s occult secrets. In truth, Freemasonry is only a few centuries old, and like the American Constitution, is very much a product of the Enlightenment. The first Masonic Grand Lodge was founded in England in 1717; the first American lodge opened in Philadelphia in 1731 with Benjamin Franklin as a charter member. There are numerous varieties of Masonry (the York Rite, the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite, the Knights Templar, the Order of the Eastern Star, Royal Arch Masonry, and more). Some, like the Knights Templar, are explicitly Christian, but the ethos that most subscribe to is best described as humanistic deism. And if the Masons have a consistent class identity, it is bourgeois.

It’s not surprising that George Washington and Benjamin Franklin were Masons. Both were non-churchgoing men of affairs, devout republicans who were good with money and conversant with science (especially Franklin, though Washington studied and applied the agronomy of his day, experimenting widely with new techniques in planting, plowing, manuring, and crop rotation). Other prominent American Masons of the period were Paul Revere, John Marshall, John Hancock, and James Monroe. Among Europe’s well-known eighteenth-century Masons were the Marquis de Lafayette (an aristocrat to be sure, but something of a class traitor), and Goethe, Mozart, and Voltaire. In South and Central America, Simón Bolívar, El Libertador, was a Mason. There have been very conservative and racist Masons too. Albert Pike, for example, was a leader and major theorist of the Scottish Rite, one of the most speculative and esoteric varieties of Freemasonry; he was also a Confederate general, an avowed white supremacist, and active in the early KKK. But most were progressive-minded representatives of the rising Protestant middle class.

Esoteric Masons’ engagement with arcana like Greco-Egyptian hermeticism, Gnosticism, Kabbalah, the Koran, and alchemy came from the same place as their interest in science — a wide-ranging curiosity unfettered by religious dogma, and the confidence that human beings are inherently perfectible, that anyone can work and study their way toward wisdom, happiness, and spiritual integration as they ascend through the degrees of the Craft. This is a very different view of the human condition than Catholicism’s or Calvinism’s, which maintain that mankind is inherently depraved and cannot earn grace, but only be granted it by Christ, either directly or via the church’s intercession. That is why the pope condemned Masonry in 1738, a ban that was reaffirmed as recently as 1983 by Cardinal Ratzinger when he was prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, formerly known as the Roman Inquisition (in 2005, he would become Pope Benedict XVI).

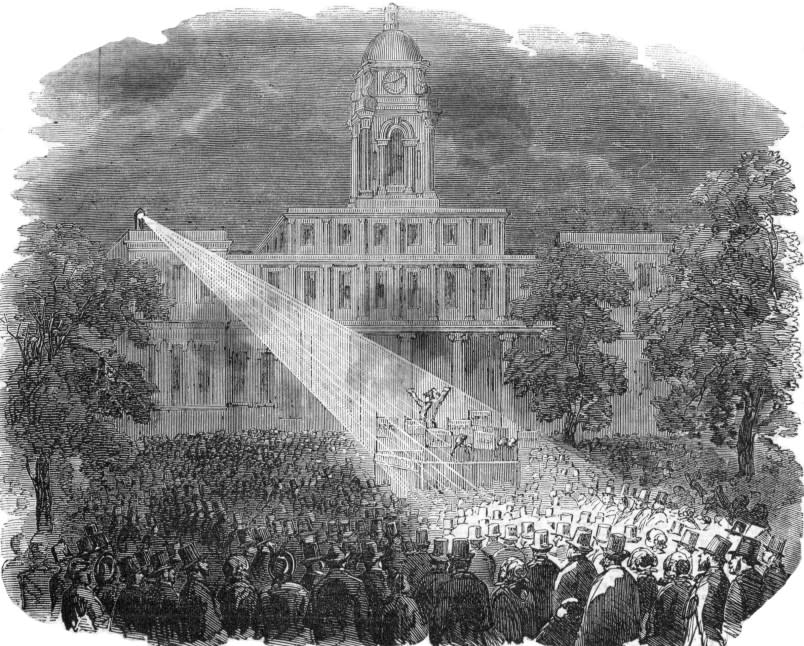

Freemasonry came under fire in the United States in the 1820s, after William Morgan, a former brewery owner and veteran of the War of 1812, disappeared after he’d written an exposé of Masonry and sold it to a publisher. If the Masons murdered him to protect their secrets, as was widely supposed, their plan backfired spectacularly. Morgan’s book was published posthumously as The Mysteries of Freemasonry, Containing All the Degrees of the Order Conferred in a Master’s Lodge. The controversy surrounding the disappearance snowballed into a full-blown national political movement with the formation of the Anti-Masonic Party, whose bête noire was Andrew Jackson, the former grand master of Tennessee.

Jackson is remembered today as a populist and an avowed enemy of the permanent Washington establishment. Donald Trump declared himself a Jacksonian during his first presidential campaign in 2016; after he was elected, he hung Jackson’s portrait in the Oval Office and visited his grave. But in Jackson’s own day, his enemies castigated him as an elitist and would-be despot. Some of that animus was likely personal. John Quincy Adams had eked out a win against Jackson in 1824, but lost the presidency to him in 1828 after an especially vicious campaign. Though Adams enjoyed a long and consequential ex-presidency as a lawyer, abolitionist, and member of Congress, he devoted a surprising amount of his energies in the 1830s to anti-Masonry, even writing a book, Letters on Freemasonry, in which he attacked the Masons as “a conspiracy of the few against the equal rights of the many” and “a seed of evil, which can never produce any good.” Freemasons take oaths binding them to their order instead of to the republic, Adams said — so how patriotic could they be?

His book exhaustively cataloged the ghoulish tortures that Masons supposedly visited on disloyal members like Morgan, lovingly detailing the cuttings of throats, tearing out of hearts, and “smiting off the skull to serve as a cup for the fifth libation” that were the penalties for disloyalty. And he called explicit attention to Masonry’s resemblance to Catholicism, which was also accused of torturing its apostates and putting loyalty to the pope before loyalty to the nation (much as Jews are accused of doing with Israel today).

If I seem to be downplaying the potency of anti-Black racism and anti-Semitism, I’m not. Remember, my topic is not prejudice per se, but paranoid conspiracy theorism. For much of American history, racism has been openly acknowledged and supported by the force of law. As such, Blacks themselves weren’t so much the objects of conspiracy theorist thinking as their non-Black allies in the Abolition and the civil rights movements were.

As for anti-Semitism, once The Protocols of the Elders of Zion began to be widely translated after the turn of the 20th century, conspiracy theorists of every stripe off-loaded the wicked attributes of Catholics, Masons, Illuminists, anarchists, robber barons, bankers, and revolutionaries onto Jews. Judaism was said to have co-opted the Masons, just as it had labor unions and other progressive movements, to undermine the power of the state. “Gentile masonry blindly serves as a screen for us and our objects,” says Protocol 4. “Until we come into our kingdom ,” Protocol 15 adds, “we shall create and multiply free masonic lodges in all the countries of the world, absorb into them all who may become or who are prominent in public activity, for these lodges we shall find our principal intelligence office and means of influence.”

The Holocaust was the culmination of 2,000 years of successionist theology, the belief that Christianity completed and nullified both the Judaic law and Judaism itself, and of a century of political and social resentment as Jews throughout western Europe were finally made citizens of their countries.

But Jews were relative latecomers to the global conspiracy theories that formed the basis of Nazism, and that they still feature in so largely today. The person who gave American anti-Semitism its biggest platform ever was the industrialist Henry Ford. “There is a race, a part of humanity,” he wrote of the Jews in The Dearborn Independent, the newspaper he purchased in 1918 and mostly used to promote The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, “which has never yet been received as a welcome part, and which has succeeded in raising itself to a power that the proudest Gentile race has never claimed, not even Rome in the days of her proudest power.”

Though the Jews were still nationless, Ford and his White Russian ghostwriters cast them as the world’s most rapacious imperialists. Though most of the Jews who had begun pouring into America from eastern Europe toward the end of the nineteenth century were penniless, they were presumed to be fabulously wealthy. “The Protocols do not regard the dispersal of the Jews abroad upon the face of the earth as a calamity, but as a providential arrangement by which the World Plan can be the more certainly executed,” Ford wrote. The Diaspora was a punishment the Jews not only deserved but had freely chosen; as such, they should not be pitied but despised and feared. Ford’s anti-Semitism was monstrous, but you can at least understand where it came from. He had heard it proclaimed from the pulpit by Protestant ministers as a child, and he read it in the tracts of the agrarian populists.

Ford had a sentimental attachment to the rural America that formed him, which caused him no end of cognitive dissonance, because if he couldn’t find someone else to blame for its decline, he might have had to take a critical look at himself. Economists still use the term “Fordism” to describe the standardized, mass-production consumer economy that transformed small-town America into a patchwork of look-alike cities and suburbs. Mass-produced automobiles literally and figuratively released rural people from their ties to the land. Underemployed farm laborers moved to Detroit to work in Ford’s factories, and the cars Americans bought on credit not only made them mobile but provided young people and adulterous marrieds with trysting places.

Ford’s anti-Semitism exonerated him not just for the ruination of the wholesome way of life that he remembered, but the ruthlessness of the capitalism that he practiced. That which we call capitalism, he explained in The International Jew, is an illusion, because “the manufacturer, the manager of work, the provider of tools and jobs — we refer to him as the ‘capitalist’ himself must go to capitalists for the money with which to finance his plans.” The common enemy of both labor and capital, he wrote, is “super-capitalism, a super-government which is allied to no government, which is free from them all, and yet which has its hand in them all.” To save America, to save the world, those super-capitalists must be crushed. “If the Jew is in control,” Ford asked, “how did it happen? This is a free country. The Jew comprises only about three per cent of the population. Is it because of his superior ability, or is it because of the inferiority and don’t-care attitude of the Gentiles? Unless the Jews are super-men,” Ford concluded, “the Gentiles will have themselves to blame for what has transpired.” Where is the modern Haman who will do what must be done? he might as well have asked.

Even after spending years parsing the paranoid style, the genocidal implications of Ford’s logic stuns me — as does the fact that he continues to be held up to schoolchildren as a model American entrepreneur. It really is no wonder that Germany’s rising fascists looked on “Ford as the leader of the growing Fascisti movement in America,” as a reporter from the Chicago Tribune put it in 1923. “We admire particularly his anti-Jewish policy which is the Bavarian Fascisti platform. We have just had his anti-Jewish articles translated and published,” Hitler told him. “The book is being circulated to millions throughout Germany.” The article goes on to note that Ford’s “picture occupies the place of honor in Herr Hittler’s [sic] sanctum.”

If you are seeking the origins of the American Paranoid, there are many places to look. For Protestants in the colonial era, the great historical adversary was Satan, as embodied in the Catholic Church. The dread this transnational superstate inspired was virtually hardwired into their psyches, like the fear of snakes. At the same time, I suspect, they felt an unconscious, largely unacknowledged nostalgia for its certainties. The lineaments of that primal hatred live on in contemporary conspiracy theorists’ fever dreams about the all-powerful Illuminati, the Elders of Zion, and the hidden leaders of the Deep State, who feed themselves with children’s blood and injections of adrenochrome and interfere with the sovereignty of nations.

Both Catholic and Protestant doctrine demand that its believers repudiate Freemasonry’s values, but few Americans do, because our political institutions grew out of the same soil that Freemasonry did, which is the practical, empiricist, tolerant, and secular ethos of the Enlightenment that Sam Dickson believes poisoned the American experiment at its birth.

Religious tolerance, if not indifferentism, is what underlies Madison’s and Jefferson’s wall of separation between church and state. “It does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods, or no god,” Jefferson famously wrote. But despite the mountains of evidence that show that religious pluralism encourages rather than harms religious belief (56 percent of Americans say they believe in God as described in the Bible, as opposed to just 27 percent of western Europeans), an influential minority of religious Americans would just as soon tear it down. Many have their doubts about democratic republicanism as well. The only sure guarantor of their freedom, they say, is power — specifically, the ability to wield power against religions, ideas, and people they don’t like.

Adapted from The Politics of Fear, copyright © 2024 by Arthur Goldwag. Published by arrangement with Vintage Books, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.