‘The biggest barrier is us.’ Existence of overdose prevention centers slowed by stigma

Cheryl Juaire lost two of her sons to the opioid epidemic.

Her son Corey died of an overdose in 2011. A decade later, she lost Sean under the same circumstances.

Juaire, founder and president of the nonprofit Team Sharing Inc., advocates for overdose prevention centers in Massachusetts.

The centers, also known as "supervised consumption sites" or "safe injection sites," are places where participants can consume pre-obtained drugs under supervision.

The evidence-based approach is designed to minimize the negative health effects of drug use, such as overdose death and disease transmission. The centers typically include sterile equipment, drug testing and referrals to treatment, according to the Drug Policy Alliance.

'That's not enough': Marlborough group pushes Gov. Baker on opioid deaths

“I would have driven my kids there if I could have one more day with them,” said Juaire, who lives in Marlborough.

As opioid-related overdose deaths climb in Massachusetts, support for overdose prevention centers has grown. However, advocates said a stigma around drug use impedes it from becoming a reality.

“The whole goal is to keep them alive one more day,” Juaire said. “To me, it’s really a no-brainer.”

The state Department of Public Health recommended the establishment of overdose prevention centers in a feasibility report released in December.

“DPH is committed to reducing overdose deaths and ensuring that individuals in the state have access to the harm reduction, treatment and recovery services they need, when they need it,” a DPH spokesperson wrote in a statement.

Massachusetts' opioid crisis and current harm reduction

For more than 30 years, overdose prevention centers have operated in Canada, Australia and parts of Europe. There has never been an overdose death reported at a center, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Brandon Marshall, a professor of epidemiology at the Brown University School of Public Health, supports overdose prevention centers due to the evidence.

“They're not a new intervention,” he said. “Although this is a new model of addressing the overdose crisis in the U.S., we can look to scientific studies from other countries and have high confidence that they will reduce overdose deaths.”

The DPH reported approximately 2,359 opioid-related overdose deaths in Massachusetts for 2022, according to the most recent data. That's up 3% from 2021 and a 16% increase from 2019.

Opioid-related overdose deaths spiked as a result of an increased presence of fentanyl in the illegal drug market, experts have said. Fentanyl was present in 93% of toxicology reports of opioid-related overdose deaths in 2022, according to DPH data.

The synthetic opioid is 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine, and it's often used to adulterate other drugs, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Massachusetts invested $1.2 billion in substance use and harm reduction programs from 2015-22, according to the DPH feasibility report.

'Lives are at stake': Franklin state rep again pushes for safe injection sites

The commonwealth operates 60 state-funded Syringe Service Programs — also known as needle exchanges — providing access to sterile needles and syringes to reduce the risk of disease transmission.

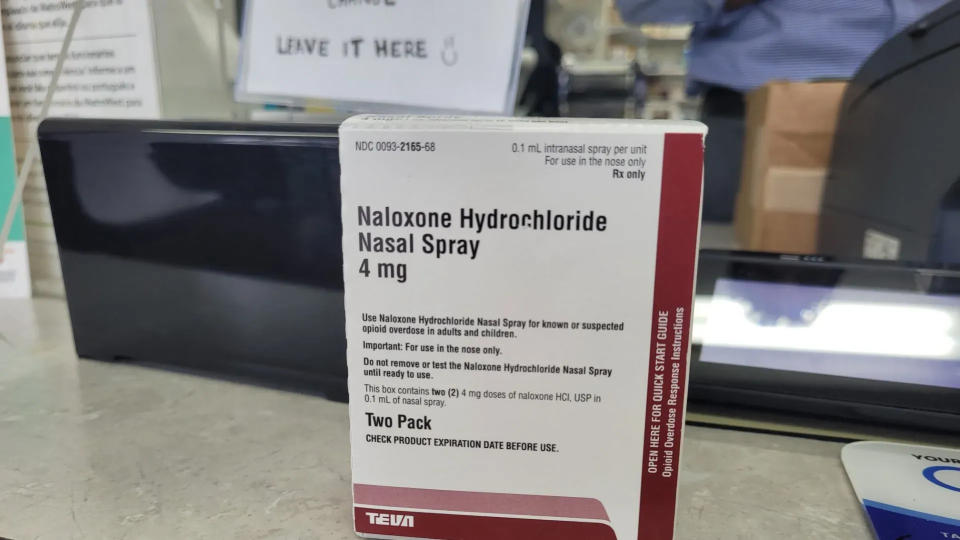

The Healey-Driscoll administration has funded several existing harm reduction measures, such as the increase in fentanyl test strips, expansion of the 24/7 overdose prevention hotline and an increase in the distribution of naloxone — an opioid overdose-reversing medication.

Dr. Jessie Gaeta, an addiction medicine specialist with the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, said overdose prevention centers are needed as another part of the addiction service continuum.

“This is only one part of the strategy for a community," she said. "There is not a single answer to this issue. There are lots of things that are needed. This is definitely one of them.”

Overdose prevention centers would also save Boston an estimated $4 million by preventing emergency room visits and hospitalizations, according to a 2021 report by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review.

NIMBYism and arguments against overdose prevention centers

Not in my backyard, or “NIMBYism,” is a common response to overdose prevention centers, Marshall said. This is the fear that the existence of these centers will attract people who use drugs, drug dealers, drug-related crime and drug-related waste to their communities.

“Hopefully, by pointing to the evidence and educating neighbors and the public, you can start to see a shift in those perceptions,” Marshall said.

But state Rep. Lindsay Sabadosa, D-Northampton, said the opioid epidemic is so widespread that it has already reached everyone’s backyard.

“Drug use is happening all the time," she said. "It's happening as we're speaking right now somewhere in our community. There’s no such thing as 'not in my backyard' because you can turn a blind eye but it's already there.”

Since the opening of OnPoint NYC — two overdose prevention centers in Manhattan — there were no “significant changes in measures of crime or disorder” where the centers were located, according to a 2023 study.

OnPoint NYC also found a reduction in syringe litter and hazardous waste in the community in its own annual report. About 12,000 fewer syringes were collected in the park across the street from the Washington Heights location in the first month after the facility opened.

“There have been many studies that have looked at the neighborhood-level impacts,” Marshall said. “They demonstrate, time and time again, improvements in neighborhood conditions.”

Cambridge official seeks overdose prevention centers in every community

To mitigate the fear of one site becoming a “magnet,” Marc McGovern, a Cambridge city councilor and former mayor, said there needs to be overdose prevention centers open in every community.

“Let's do some regional planning for once in Massachusetts,” he said. “We’re going to do this together so that no one community is going to carry the responsibility.”

'Maybe we're turning the corner': Task force official says 'it takes a village' to conquer opioid crisis

Dr. Bertha Madras, a professor of psychobiology at McLean Hospital and Harvard Medical School, said taxpayers don't want to “facilitate addiction” by making drug use easier.

“These people obviously have an influence on the politicians who vote for appropriations for these facilities,” Madras said.

Marshall said there is a “pervasive myth” that overdose prevention centers enable drug use, which is “simply not true.”

“Implementing harm reduction measures doesn’t enable, it prevents people from dying,” Sabadosa added. “It enables life.”

Another point of concern among people opposed to overdose prevention centers is their “hard-earned” tax dollars funding it, Madras said.

However, there are ways to fund overdose prevention centers outside of state dollars.

Foundations and philanthropy fund the observation of drug use at OnPoint NYC. Meanwhile, opioid settlement dollars, private foundations, grants and individual donors fund a center set to open in Providence later this year.

Pending Massachusetts bill barred by stigma

A bill presented in February 2023 would establish a 10-year pilot program for overdose prevention centers in Massachusetts.

Under the legislation, a local board of health must approve its establishment. The center must also include sterile equipment, referrals to treatment and data collection.

The bill was voted favorably out of the Legislature’s Joint Committee on Mental Health, Substance Use and Recovery and referred to the House Ways and Means Committee.

It has 17 co-sponsors in the Senate and 58 representatives in the House. Lawmakers have until July 31 to act or the measure will need to be refiled next year.

OPINION: Safe injection sites ignore the real problem

Sabadosa, a co-sponsor, said support for the legislation has “grown exponentially” during her five-plus years in office, but there is still “fear of the unknown.”

“Many people still have a lot of stigma related to drug and drug usage,” she said. “That can impede progress on legislation like this.”

A Beacon Research survey found that 70% of Massachusetts voters support the bill. But advocates said the stigma around drug use is a roadblock to the bill passing.

“We believe, generally speaking as a society, that addiction is a moral failing, that it is something to be punished,” Gaeta said. “The biggest barrier is us.”

She said overdose prevention centers run “so counter” to this common view of addiction that people may have a difficult time understanding why they will be helpful.

In Cambridge, 80 people died of opioid-related overdoses from 2019-22, according to DPH data.

“If 80 people had died for any other reason in Cambridge in a four-year span, people would be marching on City Hall to do something about it,” McGovern said. “And we do almost nothing.”

Marshall said another “critical driver” of stigma is different responses in drug policy when different populations are affected.

“You can’t extract structural racism from stigma and drug policy in the U.S.,” Marshall said.

McGovern said the way to overcome that stigma is education.

When given more information about overdose prevention centers, voter support for the bill jumped 9%, according to the Beacon Research survey.

“When you sit down with a policy-maker or a concerned community member or students and walk through what they actually do and the evidence base to support them, you can really go a long way,” Marshall said.

Jim Stewart, steering committee member for SIFMA Now, said public officials need to “challenge the ignorance of their constituents.”

“At some point, people who take on the mantle of leadership have to challenge their constituents or their followers to take a second look at something,” Stewart said.

'Crack house’ statute and legality of overdose prevention centers

But overdose prevention centers in Massachusetts also face a potential legal battle. They could be deemed illegal on both federal and state levels.

The Massachusetts Controlled Substances Act makes it illegal to possess certain controlled substances without authorization.

Meanwhile, the federal “crack house” statute makes it illegal to own or operate a property for the purpose of “manufacturing, distributing or using any controlled substance.”

The statute — enacted in 1986 — is intended to ban houses and buildings where drugs were manufactured and used, according to a Boston drug crime lawyer’s website.

McGovern said there's an unclear legal standing of overdose prevention centers because it's not the intention of the statute.

“There's certainly a lot of attorneys out there who I think would argue pretty convincingly that this isn't illegal,” he said.

But without authorization, Marshall said there are “real risks” to people who work at such centers.

The pending Massachusetts bill includes language protecting participants, staff, property owners and operating entities from legal action, including professional licensure.

Sabadosa added that grassroots overdose prevention centers are popping up all over the place.

“This bill really just takes a big step forward in allowing people to step out of the shadows,” she said.

OnPoint NYC currently operates without federal or state authorization. Before the centers opened, then-Mayor Bill de Blasio ensured that law enforcement and local district attorneys would not take action. However, a top federal prosecutor in New York threatened to shut down the centers last year.

In Philadelphia, Safehouse, a nonprofit that provides overdose prevention services, is entrenched in a years-long legal battle with the U.S. Justice Department over a proposed overdose prevention center.

Safehouse’s argument centered around religious grounds under the First Amendment, making the center constitutionally protected. A federal judge recently dismissed the case.

Rhode Island was first to authorize overdose prevention centers

Rhode Island was the first state to authorize overdose prevention centers, in 2021. Project Weber/RENEW, in partnership with VICTA, is set to open the state’s first center later this year.

Marshall said he's not aware of any federal pushback to the center. The National Institutes of Health, a federal agency, funded a research study to be conducted at the center through a grant.

Minnesota also authorized overdose prevention centers through a budget process in 2023.

Advocates urge Massachusetts to take the risk and join other states at the forefront of the movement.

“Many things have changed in our society because someone challenged them legally,” McGovern said. “Maybe that's what we have to do here.”

Somerville plans to open Massachusetts' first overdose prevention center, forgoing official authorization. The city approved $827,000 for the center in March 2023.

'Huge leap forward': Why does Somerville need supervised consumption sites?

The Worcester Board of Health unanimously approved the creation of an overdose prevention center pilot program in March. However, plans will not move forward unless the state grants approval.

Worcester recorded the highest rate of opioid-related overdoses in Massachusetts in 2022, according to DPH data.

Dr. Matilde Castiel, commissioner of Health and Human Services in Worcester, said local residents were “favorable” to overdose prevention centers.

“It brings it to the forefront. I think that good conversations are happening,” Castiel said. “It lets other cities know that they can do the same thing.”

Health experts prioritize access to treatment

If overdose prevention centers become reality in Massachusetts, Gaeta said it would be ideal to “co-locate” these centers with addiction treatment.

In Vancouver, the Insite overdose prevention center operates with supervised consumption on the first floor and both short-term beds and long-term recovery services on the upper floors.

“It breaks down barriers to moving through the continuum,” Gaeta said.

Madras said it would be “inhumane” and “short-sighted” if the center was solely a place to consume drugs.

“I firmly believe that every human who has substance use disorder should be given the opportunity to enter treatment and to recover from a brain disease that could kill them,” Madras said.

A study out of Vancouver found a 30% increase in the uptake of detox services within a year of the center's opening.

OnPoint NYC reported that one in five participants were referred to housing, detox, treatment, primary care or employment. The center also reported 2,841 unique participants at the center in its first year and 636 interventions to prevent overdose death.

Madras said these centers should also provide access to FDA-approved medications for treating opioid-use disorder and equip participants with naloxone.

Support for overdose prevention centers gaining momentum

With the opioid crisis growing, Marshall said so many people are affected that it creates an understanding of the need for “new approaches.”

“Everybody’s been affected somehow, somebody knows somebody,” Juaire added. “It's not till that happens that movement happens, change happens.”

Sabadosa said she doesn’t know whether the bill will pass this session, but legislators are realizing “it's the morally right thing to do.”

While Gaeta said she believes overdose prevention centers will be a reality in Massachusetts eventually, there is an urgency as opioid-related overdose deaths continue to climb.

“I have felt pretty frustrated by our inability to do this yet, but I think it’s coming,” she said. “I’m also just tired of seeing people die.”

This article originally appeared on MetroWest Daily News: Stigma slows Massachusetts progress on overdose prevention centers