The Fort Worth Star-Telegram sent reporters into World War II. One paid the ultimate price

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Our Uniquely Fort Worth stories celebrate what we love most about Cowtown, its history & culture. Story suggestion? Editors@star-telegram.com.

In reflection of the recent 80th anniversary of D-Day, I wanted to recognize two of the five Fort Worth Star-Telegram World War II correspondents to share the stories of these reporters behind their bylines.

Flem Hall and Stanley Gunn were reporting from overseas during the invasion, working to fulfill one directive from Star-Telegram publisher Amon G. Carter: bring home stories about Texas soldiers. Reporting on the war was complicated, given that information concerning military operations was censored and only official statements issued by military authorities were disseminated. The objective for Star-Telegram correspondents, however, was to provide readers back home with “a closeup, direct-from-the-scene picture of how their sons and brothers and sweethearts live, what they do, what they think, and how they fight.”

Hall began at the Star-Telegram in May 1922 and served as the paper’s sports editor and later sports director during his 45 years at the paper. Gunn, freshly equipped with a journalism degree from the University of Texas, began at the Star-Telegram in 1943 as a staff writer.

Prior to D-Day, Hall and Gunn both volunteered for the initial war zone assignments, Hall volunteering to cover Europe and Gunn volunteering to cover the Pacific. In April 1944, both Hall and Gunn traveled to New York and Washington together to complete their accreditation with the War Department. Gunn held the rank of ensign in the U.S. Naval Reserve, as he explained in an article from June 28, 1944: “As a war correspondent I am accredited to the army — not a part of it — but privileged to wear the uniform of an officer (with equivalent rank of captain, in case of capture by the enemy) and allowed to go with troops under the command of General MacArthur.”

Arrival in England before D-Day

Hall arrived in England in May 1944; he wasted no time in finding Texans preparing for combat and quickly worked toward sharing their stories. In the days leading up to the D-Day invasion, he described his 22-hour flight to England and his arrival in the war zone, detailing the beauty of the British countryside and almost casually mentioning their brief experience being in a line of gunfire from a small boat. He wrote about the housing problems in London, the breakfasts they would receive, and the level of rationing being more “tedious” than at home.

Hall reported no shortage of Texans everywhere he turned, writing, “This may not be the Lone Star State’s private war, but Texas has contributed as lavishly as any in men.” He published the names of 10 Texas pilots among the first attack forces flying over the invasion area from the base of the Thunderbolt wing in Southern England, reporting that, “It was a quiet mission. Neither air opposition nor flak of consequence was encountered and all planes returned.”

In the hour before soldiers departed for the mission, Hall describes “no visible sign of emotion, no shouting or loud talking, no backslapping of good luck wishing. It was all pretty professional … The nerveless kids who fly the stubby winged Thunderbolts knew the big show was on before their officers called them into briefing and told them officially: ‘Well, boys, this is it.’”

Hall reflected on watching the D-Day invasion from an English Channel airdrome, following the American Army’s advance across France while cheering and enthusiastic French citizens welcomed the passing Americans. Following the D-Day invasion, Hall reported that British officers were praising the U.S. Army’s accomplishments, noting that, “Nothing, they say, can now destroy the American-British friendly relationship.”

In the days and months to follow, Hall went on to publish a series of narratives relating the role that Texans in the Army Air Force (AAF) based in England were playing to take down Hitler. Of particular note within these articles are the datelines, which were phrased in such a way as to not disclose confidential location information to the enemy. These appeared under the bylines of the Star-Telegram war correspondents and often indicated locations such as “somewhere in Australia,” “aboard troopship in Pacific,” “at a Thunderbolt base in England,” and “MacArthur’s Headquarters.”

‘Somewhere in the Southwest Pacific’

Gunn arrived “somewhere in the Southwest Pacific” in late June 1944, contributing his first story as a war correspondent on June 28, 1944. The Star-Telegram, in announcing Gunn’s arrival to an undisclosed Pacific port, wrote, “The stories that [Gunn] will send back to the Star-Telegram will not relate much of the battle activities of the Texans but of the more intimate side of life off the zone of action. He will visit all the installations where Texans are stationed and will observe their recreational and relaxation activities.” In his first article, Gunn claimed that being a war correspondent was “the easiest assignment I have had. Getting to be a war correspondent, however, took endless weeks of work and worry and waiting — and no little red tape.”

Gunn also compared his experience at sea on an Army transport ship to a bus carrying a load of football players and coaches to an important intersectional football game back home, describing that there was “no worry or concern on the faces of these youngsters sprawled over the decks in shorts or coveralls, swapping gags and indulging in horseplay.”

Gunn had experiences similar to Hall’s in that he encountered Texans and stories about Texas at every turn — he reported on their marriages to Australians and their picking up of Australian slang, their experience with making Texas chili abroad, and stories of Texans reuniting with each other in a foreign land.

Gunn wrote an article about former football rivals, one a former Texas A&M Aggie, the other a former Santa Clara Broncos player, now playing for the same team as they “[fly] together to bomb [Japanese]-held installations and shipping in the Southwest Pacific.” As described by both Hall and Gunn, Texans were not difficult to spot due to their “high spirits, their devil-may-care attitude, and their belligerent patriotism for their home state.”

A homecoming and death in the Philippines

Hall returned home from Europe on October 13, 1944. Upon his return, Hall was quoted in an article by colleague Robert Wear (who would be next to serve as a Star-Telegram war correspondent overseas), lamenting that “words don’t do the job — nothing has seemed to make most of the people here at home realize what the war is like, and what it is doing to the people who are in it.”

While Hall was settling into life back home in Fort Worth, Gunn was dispatched with Gen. MacArthur’s forces in the Philippines and landed with the fifth wave of American troops on the island of Leyte on Oct. 20, 1944, termed “A-Day.” Gunn describes that the Texas flag flew in Leyte as the 1st Calvary Division arrived to the island.

Just days later, Gunn sustained severe injuries from a Japanese bomb that exploded next to his quarters. On Oct. 28, 1944, Gunn died, only a few weeks prior to his scheduled return home. Colleagues and friends buried Gunn in the U.S. Army cemetery in Tacloban, Leyte; later his remains were exhumed and re-interred in Austin, Texas.

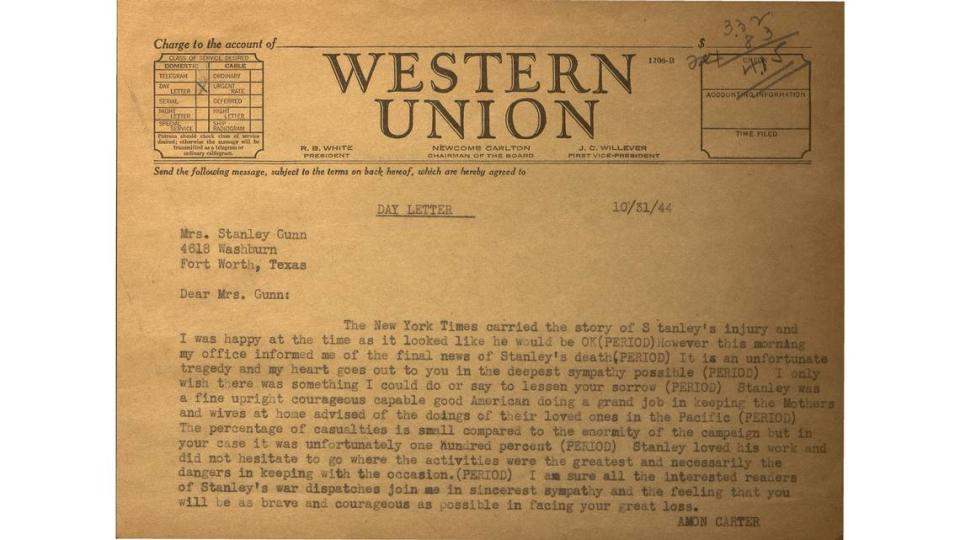

Amon G. Carter sent his condolences via telegram to Gunn’s widow, Catherine Gunn, after his death, writing that, “Stanley was a fine, upright, courageous, capable, good American, doing a grand job in keeping the mothers and wives at home advised of the doings of their loved ones in the Pacific.” According to the Freedom Forum, 67 war correspondents were killed in action during WWII. Gunn was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart and honored with a presidential citation.

Sara Pezzoni works towards promoting greater access to Fort Worth Star-Telegram archival collection materials as a staff member of the Special Collections department at the University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.