John Burnside, vivid poet and memoirist whose work was influenced by a brutal childhood – obituary

John Burnside, who has died aged 69, was one of the most acclaimed writers of his time in both prose and verse, equally compelling whether his subject was the beauty of the natural world, or the drink-fuelled years in which he would habitually begin the day by “hauling myself out of a skip behind a pet shop”.

Burnside seemed a Jekyll and Hyde figure in his early career: his poetry, as he put it, tended to be “celebratory and lyrical”, while his novels, in the view of one critic, displayed “a livid streak of psychopathy” with a focus on murder, rape and torture.

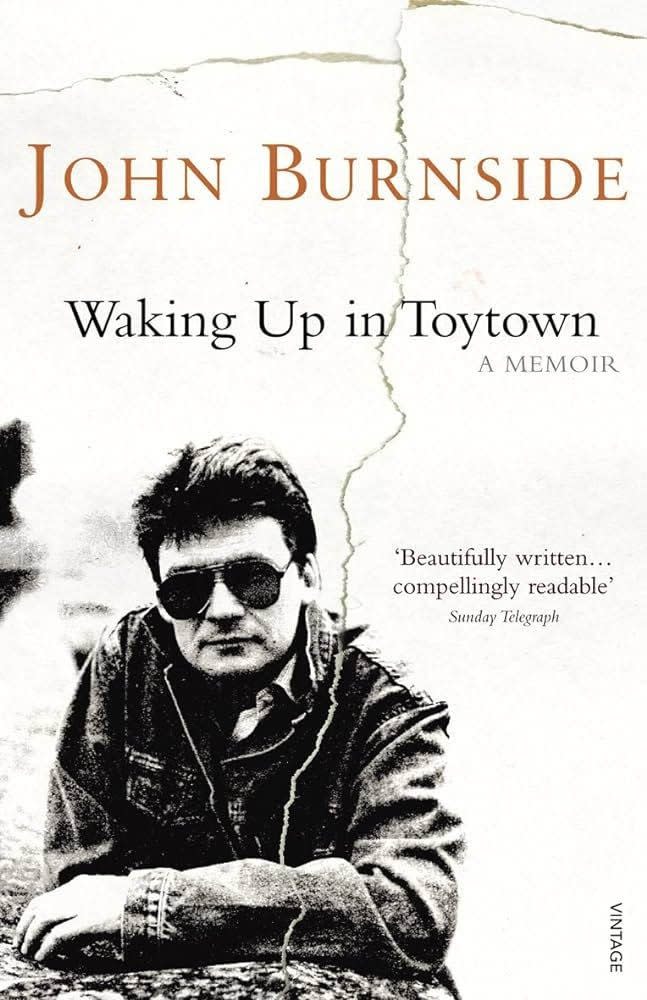

Three superb volumes of memoir – A Lie About My Father (2006), Waking Up in Toytown (2010) and I Put a Spell On You (2014) – eventually accounted for this seemingly split personality. A traumatic childhood, followed by years of mental illness and drink and drug abuse, explained his preoccupation with the darker aspects of life. But his tribulations had also led him, since boyhood, to seek refuge in the wonders of nature, which he duly hymned in verse.

In his poem “Lost” Burnside recalled roaming Beath woods, near his childhood home in Cowdenbeath, Fife, “where I was gone / for ages, on those Sunday afternoons / lost on purpose, looking for the lithe / weasel in the grass… I wanted the pink-toothed / killer… who slips into the chicken runs of mind / and works his way with something of my own / bright rage towards the folly of the damned.”

The boy’s “own bright rage” is explained in his memoirs’ depiction of his drunken father, who once threw John’s sister down the stairs, and threw his favourite teddy bear into the fire.

The young John’s misery was compounded by the family’s relocation to the soulless Midlands new town of Corby when he was 11. “I gave up on social engagement altogether. Now all that remained was the consolation of ecology.”

For many years he lived a rackety existence peopled by oddballs (one of his memoirs bore the disclaimer: “Some of the characters, especially the homicidally inclined, have been camouflaged for their own protection.”). He “tried to be normal, and… failed – not because I hadn’t tried hard enough, but because, unlike madness, normal was a lie.”

In later life, despite having some claims to respectability as a garlanded poet and an academic – from 2009 he was Professor of Creative Writing at the University of St Andrews – Burnside remained a committed anarchist. His novel Glister, he noted, featured, as a representative of capitalism, “a one-dimensional man who only cared about money. Some people criticised me. And then 2008 happened. Sorry, but I rest my case.”

Burnside strove to be less didactic in his poetry than in his prose, but he often lamented in verse the growing disconnect between humans and the natural world: “a steady delete / of anything that tells us what we are, / a long / distaste for the blood warmth and bloom / of the creaturely.”

Burnside was a lapsed Catholic, but he found a purely rational approach to life limiting, and his work was populated by angels and other evanescent presences. Certain images served as motifs: the Daily Telegraph critic Robert Hanks admitted to a “temptation to play Burnside bingo – a point for every ghost, vanishing or snowfall.”

He would feed his imagination with solo walking jaunts in the Arctic Circle; once, he got lost in a snowstorm and only stumbled on his almost-buried rental car by chance. “That wasn’t the dangerous part. The dangerous part was when I had to phone my wife and tell her I’d been out on foot without a compass while it was snowing,” he told the Telegraph.

John Burnside was born in Dunfermline on May 19 1955, the son of George Burnside, a factory worker, and his wife Theresa. He recalled lying in wait one night, as a teenager, to stab his hated father as he returned from the pub. Burnside Sr’s life was saved by his happening to be accompanied by a friend.

“What he wanted,” Burnside wrote, “was to warn me against hope, against any expectation of someone from my background being treated as a human being in the big hard world. He wanted to kill off my finer – and so, weaker – self.”

And yet the son’s portrayal of his father was full of sympathy for him and the many working-class men like him. “In a society that worked so hard to keep us from loving, or even liking, ourselves, expecting us to love somebody else… was a bit much to ask.”

After being expelled from school in Corby in Northamptonshire for smoking cannabis and fooling around with girls, Burnside found refuge in LSD and books. He studied at the Cambridge College of Arts and Technology, but went on to take menial jobs while drinking and gambling with abandon.

A slide into mental illness, fostered by “the constant tension of the household when I was in my teens”, was exacerbated by his mother’s death from cancer: his father accused him of killing her through worry. Burnside began “seeing things that weren’t there. Hearing voices in the background static. Finding God or the devil in the last scrapings of Pot Noodle.”

After treatment at Fulbourn Mental Hospital, he decided to pursue an ordinary life in suburbia – “a perfect banal” among “those isolates who make clockwork of their existence” – hoping he might settle down with a woman who resembled his television crush, the arch suburbanite Margo as played by Penelope Keith in The Good Life.

In 1985, aged 30, Burnside moved to Surrey and worked as a civil servant and later as a computer software engineer. Yet he continued to drink to excess and to find himself in unsuitable relationships: a liaison with a woman who would dope her children with Valium and leave them to go out on the town; a friendship with a fellow drinker who invited Burnside home one night and then begged him to murder his sleeping wife; an unconsummated amour fou for a 15-year-old girl when he was 38.

He had started to write poetry to provide himself with some intellectual stimulation at work, and his first collection, The Hoop, was published in 1988. He began to move in London literary circles, and although initially his drunken rages caused some alarm, he began to curb his excesses in his 40s. He married Sarah Dunsby in 1996 and eventually settled quietly in rural Fife.

The books began to pour from him, and he won the Whitbread poetry book of the year award for The Asylum Dance (2000). His collection Black Cat Bone (2011) received both the Forward Prize and the TS Eliot Prize.

Of Burnside’s first three novels, The Dumb House (1997) was narrated by a Mengele-like scientist who carries out horrifying experiments on his own children; The Mercy Boys (1999), was a portrait of the violent Scottish pub culture his father had been part of; and The Locust Room (2001) was inspired by the Cambridge Rapist, who had been at large when Burnside lived in the city in the mid-1970s.

Many readers found his early novels hard to stomach, but his fiction became noticeably less macabre after he had exorcised some of his demons in writing his memoirs. Later novels such as A Summer of Drowning (2011), set on a small island in the Arctic circle, were characterised by the same shimmering lyricism and awestruck sense of beauty as his verse.

Burnside also published collections of short stories and essays, and was a nature columnist for The New Statesman. The Music of Time (2019), an idiosyncratic history of 20th-century poetry, excoriated modern vices, among them “the feckless amateurism of unchecked ‘self-expression’ ”.

With an accent described by one interviewer as “a curious hybrid of Cowdenbeath and Corby”, Burnside was a large, burly man with, in his later years, a gentle manner.

He suffered for years from insomnia, and in 2020 almost died from heart failure: “There was light, but I didn’t just see light: I was in light, of light,” he recalled. His experiences inspired his 2021 verse collection Learning To Sleep.

The abiding inspiration for most of his poetry remained the fauna to be found near his Fife fastness, in the local woods with their silence “like the caught breath of the choir before they sing the Kyrie”.

John Burnside was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1998 and of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 2016. Last year he was awarded the David Cohen Prize for his body of work.

His wife survives him with their two sons.

John Burnside, born March 19 1955, died May 29 2024