Local historian shares tales of St. Helena’s freed people during and after the Civil War

Juneteenth celebrates the day the Union army reached Texas, the westernmost state of the Confederacy, and announced to the enslaved population their freedom on June 19, 1865. That was two years after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed in 1863, during the Civil War. Over the weekend multiple events across Beaufort County celebrated the holiday and local historian shared some little known history of Beaufort County from the middle of the 1800’s.

The Civil War started in South Carolina. The state was the first to secede from the Union and saw the first shots fired at Fort Sumter. That made South Carolina an early target for the Union.

After capturing Hilton Head Island and winning the Battle of Port Royal, the Sea Islands including St. Helena, were occupied by Union forces very early into the Civil War. The Union army freed 10,000 Blacks on St. Helena during their occupation, according to Bernie Wright, the former director of the Penn Center.

“So that was the beginning of the end of this oppression,” Wright said. “ June 19, 1865, parts of South Carolina had theirs earlier, right? That’s that’s when, really, the beginning began.”

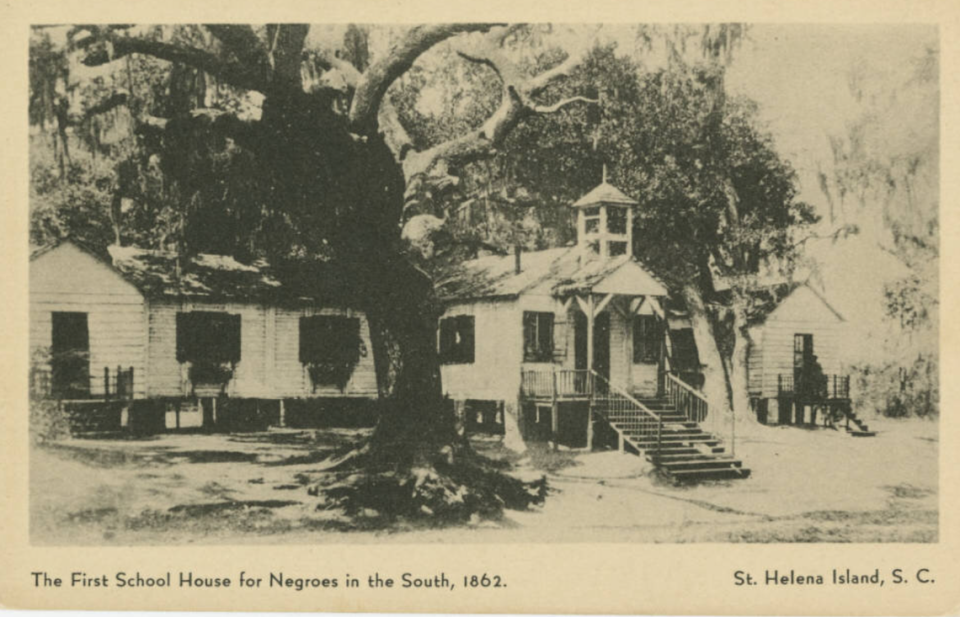

As early as 1861, the Port Royal Experiment, the first attempt at reorganizing society for a post-slavery nation, began. The Penn School, now the Penn Center, was a pivotal part of this reorganizing as one of the nation’s first schools for formerly enslaved people.

But more so than education, Wright says the biggest plight the now formerly enslaved people faced was land ownership.

“They had to be able to acquire some of that dirt, or get control of that dirt, and then from that they could grow commodities and participate somewhat, you know, in the trade industry. Selling what they grew,” he said.

And it wouldn’t be easy.

“Blacks had to apply for ownership. It had to be a husband and wife. It couldn’t be a brother-brother, sister-sister, a father and a son. But then they document this couple and they had to work for a period of time to prove that they could,” Wright said. “And they were doing the damn work all the time.”

The land the freed Blacks were given ownership of was the worst part of the Lowcountry; Boggy, marshland and sandy soil, Wright said. Ironic, because Wright said the enslaved people were the ones who learned to farm on plantations here.

“They weren’t brought over here because he can carry 200 pounds on their backs, or because they can lift like John Henry tapping down so many tracks on the railroad,” Wright said. “They were brought over here for their technical know-how. They were growing rice in West Africa before Christ was born.”

Enslaved Blacks developed a technique, using only a bar of soap, to tell when salt water was coming up the river so they could avoid ruining their rice crops. Rice, cotton and indigo were the most prominent crops in the area, at the time.

It’s worth noting that the Emancipation Proclamation didn’t solve every problem freed slaves would face. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 wouldn’t be signed nearly 100 years after the last slaves were freed in Texas. During those 100 years, Blacks in America faced countless challenges under the Jim Crow laws, from the Ku Klux Klan and the segregation of races.