With many of their books woefully out of date, NC school librarians plead for help

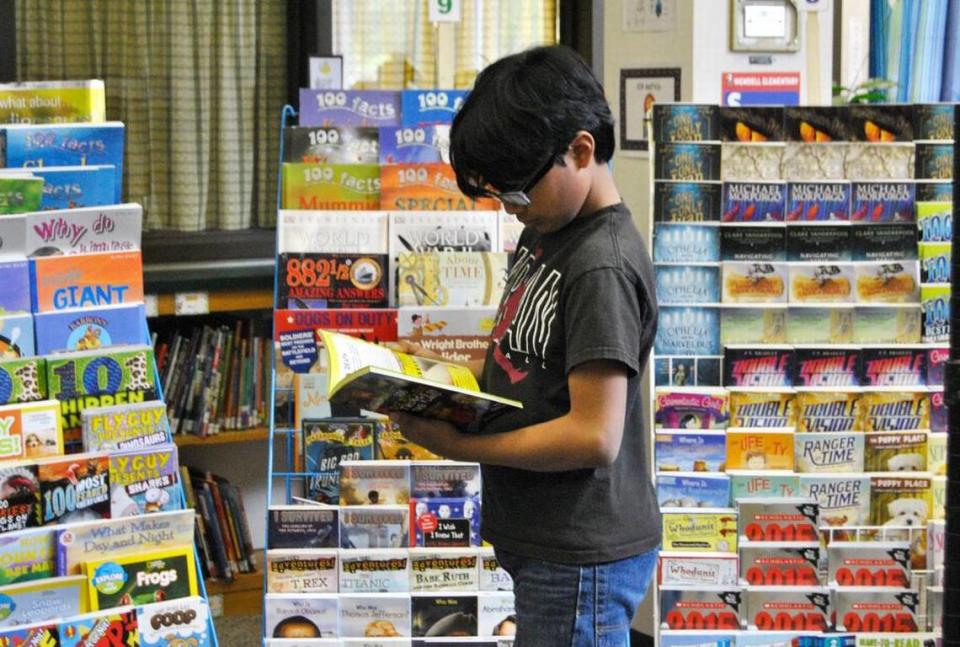

North Carolina school librarians are struggling to come up with the money they need to keep their collections up-to-date and of interest to students.

The Wake County school board received a petition this month from 158 school librarians asking the district to provide more money to purchase library books. The concerns raised in Wake, North Carolina’s largest school district, are being echoed across the state as school librarians try to update book collections that, on average, are more than 20 years old.

“We fund what we prioritize,” Chris Tuttell, the librarian at South Garner High School, told the Wake school board this month. “If you believe that literacy skills are essential and that every student should have access to books, then you must agree that all students deserve fully funded libraries.”

But that’s not an easy sell at a time when some school districts are cutting librarian positions to save money.

Librarians are also under attack from some conservative groups who accuse them of providing books to students that violate obscenity laws. Such groups want to make it easier to prosecute and fine schools.

Outdated school library collections

North Carolina is among 35 states that don’t provide direct aid for school libraries, according to SLIDE: The School Librarian Investigation—Decline or Evolution research project.

The state used to include a specific line item for purchasing school library books, according to Kristi Sartain, president of the North Carolina School Library Media Association. Now state money for school libraries is part of a general category for instructional materials.

Sartain said many school districts don’t fund school library book purchases now.

“They don’t realize books are consumable,” Sartain said in an interview. “They’re damaged. Kids lose them. They go out of date.”

The state Department of Public Instruction annually surveys schools about their library inventories. According to the last state report from the 2022-23 school year, the average school library book collection dated back to 2002. Some schools said their collections date back to 1980.

“Now we’re in a place where schools have 60% or more of their books out of date and don’t have stuff on our shelves that students want to read,” Sartain said. “If we don’t have what they want to read, they’re not going to read.”

School districts provide students with access to e-books. But Sartain said many students still want a physical copy.

Many schools not funding library books

It’s left up to the discretion of principals to decide how to spend the money they get for instructional supplies. In Wake County, 51% of schools didn’t budget any of their instructional money for library books, according to research by the Wake County chapter of the N.C. Association of Educators.

The result, librarians say, is that they need to turn to their pockets, PTA support, book fairs and grants to purchase new books. Librarians say it creates an equity issue.

“Relying on book fairs to fund our school libraries is expecting our families to pay for our school library collections,” Julie Stivers, the 2023 National School Librarian of the Year, told the school board.

“It’s unacceptable. Every student in Wake County needs access to a fully funded library no matter their ZIP code.”

Even with the outside support, many Wake school libraries reported having outdated collections. Librarians shared with the school board their frustration about not providing students with the books they want.

“It’s never easy telling students when or if we’ll be getting the latest Dogman book or the next Harry Potter book or a biography on the latest pop star,” said Evelyn Bussell, librarian of Leesville Road Middle School in Raleigh. “It never gets easier telling students that I don’t have a book on that non-fiction topic you have a project for your class. Or I do, but it’s so outdated it’s from when I was in elementary school in the ‘80s.”

Wake defends library funding model

The librarians told the Wake school board they want a reliable and stable funding stream for new library books.

Tuttell, the librarian, said they want the district to require schools to set aside $10 per student each year for library books. The average cost of a library book, according to School Library Journal, is $21.

Wake defended the current funding model, saying it allows each school the flexibility and autonomy to allocate resources based on their unique needs.

“By not restricting funds to specific categories, schools can address unexpected needs and opportunities as they arise,” Wake said in a statement.

But the school system also said it would continue to “explore ways to ensure that all areas, including our libraries, receive the resources they need.”

“We deeply value our librarians who play a crucial role in supporting our students’ education,” Wake said. “Their expertise and input are essential to creating vibrant, resource-rich learning environments. We are committed to continuing open dialogues.”