Marker honors Bloomington's nearly forgotten Black Underground Railroad conductors

.A new historical marker in Switchyard Park memorializes the vital work of conductors — specifically, Black conductors — who assisted in escorting escaped slaves north to freedom through the Underground Railroad.

But for Erin Carter, a Black Bloomington native who’s largely responsible for researching and creating the marker, it’s more than just local history; Carter’s great-great grandfather was a former slave who settled in Bloomington after the Civil War.

Carter said a goal of the marker is to highlight the Black railroad conductors and activists who contributed to the Underground Railroad system, both locally and nationally, who often are overlooked amongst the white community members who helped to facilitate the system.

“Here in Bloomington, a lot of white conductors are usually acknowledged, but I’ve never seen any real interest in Black conductors here,” Carter said. “And they were risking their own lives by doing this. So, I just think it’s really important to highlight these people as well.”

'They came up with other names': Indiana was volatile place for escaped, freed slaves

To someone looking at a map of the Underground Railroad, a place like Bloomington, which sits less than 100 miles north of the then-slave state Kentucky, may look like freedom. But local historian Liz Mitchell said even though Indiana was a “free state,” restrictive racial policies and manipulation of Black labor made it a risky place.

“Indiana wanted to claim it was a free state, so instead of ‘slave,’ they came up with other names,” Mitchell said. “So you were ‘bound out,’ or you were an ‘indentured servant.’ You would get food and a place to stay, but you’d not get paid for your labor. What’s the difference there?”

In 1851, an amendment to the Indiana state constitution banned Black people from further settling in the state and fined white people who employed or “otherwise encouraged” Black people to remain in the state.

Mitchell noted that southwestern Indiana also had a strong presence of Klan members and slave hunters who would terrorize and kidnap Black migrants.

“You just had to have brown skin, and you could be taken,” Mitchell said. “They would see people with colored skin as dollar signs, and they just took people.”

Carter said because of this volatile environment, many who came to the Monon Railroad Stockyard — where Switchyard Park is today — continued to travel north to safer areas like Chicago. But there were many, like Carter’s ancestors, who settled in Bloomington. Many, having never been taught how to read or write, entered into manipulative indentured servitude contracts.

“It’s true that there were a lot of white Europeans who were also indentured servants. But here, they really kinda tricked people, especially people of color who may not be able to read English,” Carter said.

Carter noted the histories of Black conductors in Bloomington — as well as many details of the Underground Railroad as a whole — remain difficult to find, both because the railroad system’s operations were kept covert and because Black citizens weren’t recorded in the U.S. Census until 1870.

Still, a limited number of documents — including a brief history of the Underground Railroad in Monroe County by historian and Indiana University School of Education Dean Henry Lester Smith — told the stories of local conductors like Auntie Myrears, who along with her sisters helped to conduct escaped slaves through Bloomington and harbored those seeking refuge in her house off South Rogers Street by the switchyard.

But even a local champion of the cause like Myrears is largely untraceable in archives, with her actual first name not even reflected in historical documents.

“‘Auntie’ was a term that white people called Blacks,” Mitchell explained. “‘Auntie’ usually referred to older Black women who ran the household for white people.”Carter said obstacles in research like this are a reminder for how Black people in the U.S. were treated as functionally inhuman at the time.

“Even just first names were lost, because Black people weren’t really considered human beings,” Carter said. “So their histories, and everything, weren’t important.”

Historians hope to create more historical markers around Bloomington, Monroe County

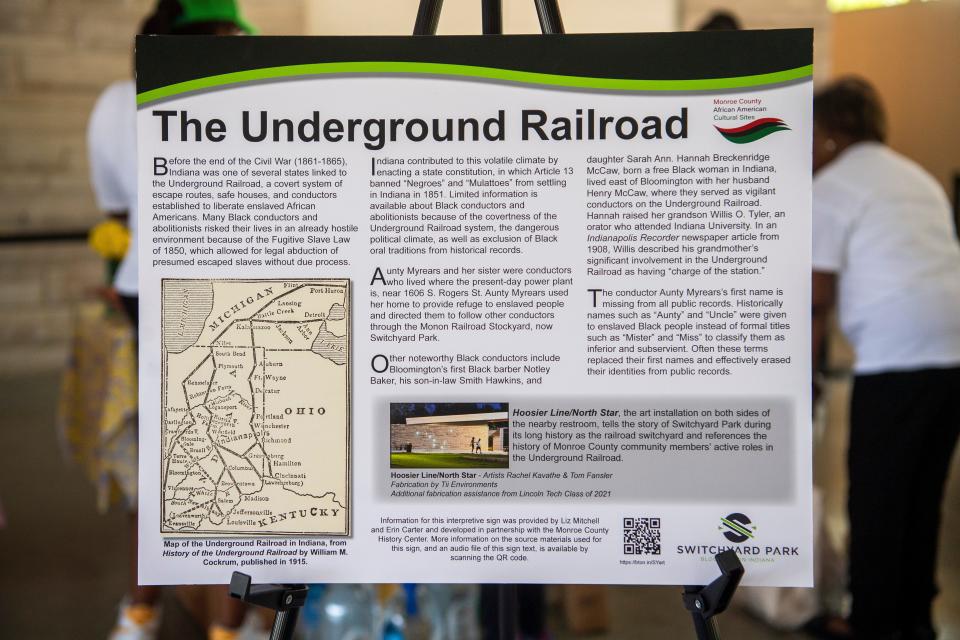

In the top right corner of the Underground Railroad marker, which will be permanently installed by the Switchyard Park splash pads this week for Juneteenth, there’s a new logo; a tri-color swoop in Pan-African flag colors that reads “Monroe County African American Historical Sites.” Mitchell hopes it’s the first of many.

In the future, Mitchell says she hopes to install markers in the current locations of bygone Black neighborhoods and communities like Hensonburg and Bucktown, strong urban neighborhoods that were devastated by racial redlining and construction of major roads.

Mitchell said Black histories are more frequently forgotten and lost, and believes it's vital to remind the local community of how Bloomington and Monroe County came to be as they are today.

“There’s a Black orphanage out on Unionville Road that’s no longer there. There was a Black daycare center on the west side, and no one knows about it,” Mitchell said. “I want to recognize that.”

Mitchell said she wants local residents to think about all elements of their local history, rather than separating out “Black history.”

“You need to know the whole story, and not half of the story,” Mitchell said. “This is not necessarily what you’d call Black history. It’s our shared history.”

Reach Brian Rosenzweig at brian@heraldt.com.

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Times: Bloomington historical marker honors Black underground railroad conductors