Mysteries and misfortune surround Wichita Falls mausoleum

Annie Jackson needs to solve a mystery. Several mysteries.

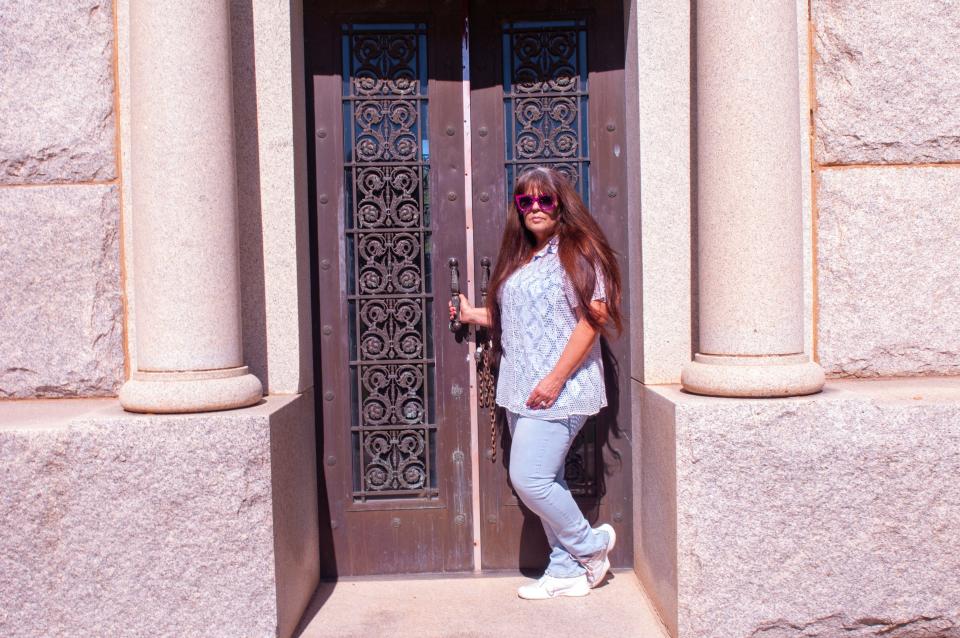

They all involve her family’s mausoleum in Rosemont Cemetery, an edifice she is now responsible for.

The mysteries involve who is entombed in the edifice — and who is not. And, more morbidly, what might be found in the crypts – or what might be missing.

The mausoleum was constructed 100 years ago by Annie’s second great-grandmother, Lillis Morgan.

Her life was a story worth its own telling.

The matriarch

Lillis Davis was born in Illinois and came to the Burkburnett area with her mother and sister before towns existed here. At age 12, she chased an intruder out of the family’s humble dugout with a hatchet. That earned her the nickname “Hatchet Girl” among the Native Americans who befriended her.

Lillis’ mother acquired some land, and Lillis, displaying the entrepreneurial spirit that would define her life, acquired land of her own. She eventually owned several ranches.

And she struck oil.

She outlived two husbands, moved to Wichita Falls, became matriarch of a large family and tackled the male-dominated business scene.

“She had several businesses. She bought the Kemp Building at 600 Eighth Street from Joseph Kemp and Frank Kell,” said Annie, wife of former City Council member Steve Jackson.

She renamed it the Morgan Building and added some extra floors. It later became the Holt Hotel.

“She was a very astute businesswoman," Annie said.

Lillis faced challenges in a male-dominated world but did not avoid fights. She became the first woman in Texas to take a traffic violation to an appeals court.

“She’s been to court many times, that woman. Even to the United States Supreme Court. She went there twice. One of them involved the Red River. She won that one,” Annie said.

Though astute, Annie said her ancestor was generous, forgiving debts owed to her by local businessmen during the Great Depression.

“The oil — one of the pumpjacks — everything it produced went to the boys’ orphanage," Annie said.

That generosity led to one of the mysteries of the mausoleum.

The mystery boy

“There is someone in there, and I’m not sure where he is,” Annie said. “His name is James Parker, and he was a 16-year-old boy when he died in a car accident.”

Lillis provided a crypt with the understanding the family would move the body later. That never happened.

“The records at the city have him here, but we’re not sure where," Annie said.

None of the crypt facings bear the boy’s name.

The mausoleum holds 32 crypts, most likely making it the largest private tomb in the city. It is a stately edifice built in the Golden Age of sepulchers.

“She liked to compete with the big boys," Annie said. "From the stories I’ve heard it would have been about, ‘Let me make sure mine lasts longer than yours does.’”

As Lillis wished, the mausoleum did last, but not without misfortunes to add to its mysteries. Rosemont is now owned by the city and located on one of the busiest streets in town.

But it was initially privately owned, and the thoroughfare was just a lonely country road. That led to vandalism. The bronze double doors have been battered, glass and locks were broken, and fittings were removed.

One family member lamented in a letter that the structure became “a dry, safe yet macabre place to sleep or celebrate.”

It got worse.

The grave robber

“There was the problem with the break-ins,” Annie said, “when they stole the skulls.”

In 1993 a grave robber broke in. Twice.

“The first attempt was with Lillis,” Annie said. “Nothing was stolen. The second time he came back with equipment.”

That time he broke into some crypts that contained bodies of family members Lillis brought from the cemetery at Clara, now a ghost town. The violated crypts included those of Lillis’s mother, Sarah Davis, and A.A. Morgan, Lillis’ second husband.

Investigators arrested a Petrolia man who led them to the Little Wichita River in Clay County where they found skulls and cemetery statuary under a bridge. The man was sent to a mental hospital, and a funeral home bagged up the skulls. No record was kept of where they went.

“I think they found four skulls,” Annie said.

Photographs taken at the time also show four skulls.

At the time of the break-in, police found evidence someone had tried to dig up a grave or graves at Rosemont, and vandalism had occurred at Riverside Cemetery. That raises questions in Annie’s mind.

“Are the remains that were returned ours? It’s my understanding this is not the only place that young man violated," Annie said. "Who all was really taken? Our concern is, do we have bodies where they’re supposed to be or did they get placed in an unmarked tomb, not knowing who they belonged to? We may have to open them all.”

As a result of the break-in, wary relatives removed two bodies and had them interred in a Burkburnett cemetery.

The tornado

The mausoleum has suffered at the hands of nature as well as humans. The tornado that struck Wichita Falls on April 10, 1979, devastated Rosemont Cemetery and damaged one side.

It was repaired but was left weakened. Heavy rains have caused ground settling. Marble crypt facings have fallen, leaving one vacant crypt eerily open. The floor in another crypt collapsed, partially exposing a casket.

The precarious side includes the remains of James A. King Jr., an Army Air Corps captain who died when his plane was shot down in World War II. A VFW post in Wichita Falls was named in his honor. His brother, Robert, used his government connections to retrieve James’s body from France.

Robert King was a naval architect who helped design Franklin Roosevelt’s war bunker and the East Wing of the White House. His ashes will be entombed when the mausoleum is repaired.

Annie believes the mausoleum holds at least 12 to 14 bodies, including three infants.

Other mysteries?

Because of Lillis’ generosity, Annie wonders if more bodies might reside in the structure. Some unmarked crypts have stains around the crypt facings.

“I think something is in there,” she said.

Annie was extremely close to her great-grandparents, James King Sr. and Willie King.

“They were the stability in my life," she said.

After they died in the late 1970s, she avoided entering the mausoleum for many years. The entombment of her brother in 2019 brought her back and sparked her determination to put things in order.

The work would entail moving caskets from the weakened side to — hopefully — empty niches on the stable side while repairs are made. It’s a daunting task that first requires getting some answers.

“I don’t want to go, 'Oh, I’m just going to move these family members.' Then work starts and all of a sudden they find another body," Annie said. "I don’t want to put any of us through that.”

Unfortunately, many of those who might know the answers to the mysteries of the mausoleum reside within it. Annie hopes there might be some still among the living.

She invites anyone with information to contact her at WFAJackson2019@outlook.com.

More: A quiet Wichita Falls neighborhood was once party central for the rich and famous

More: If walls could talk this old WF mansion would tell of wealth, power - and murder

This article originally appeared on Wichita Falls Times Record News: Mysteries and misfortune surround Wichita Falls mausoleum