School Cellphone Bans Have Buzz, but May Be Hard to Enforce

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When it comes to banning cellphones in schools, success could be determined by the details.

Do bans apply only to classrooms, or also to hallways, bathrooms and cafeterias, where students are much more likely to be absorbed in TikTok or text messages?

Do teachers have the freedom to override bans if phones are being used as part of a lesson? Should school districts purchase devices to lock or hide phones? What about distractions from other types of screens — laptops, tablets and smartwatches? And what about some parents who like the idea of being able to reach their children 24/7?

Sign up for The Morning newsletter from the New York Times

Those were just some of the questions that faced Gov. Gavin Newsom of California after he announced that his state would be the latest — after Florida and Indiana — to pursue a school cellphone ban.

Teachers who have tried to restrict cellphone use on their own said limits can be difficult to enforce, if only because phones have become so embedded into daily life, perceived as necessary for practical and emotional reasons. Yet some districts with a comprehensive policy have had success, overcoming resistance and seeing a change in student behavior.

Naomi Frierson, 44, a fifth grade teacher in the Tampa, Florida, area, said little had changed for her since Gov. Ron DeSantis imposed a statewide ban last year on smartphone use in classrooms. She had already required students to put phones in a storage pouch that hangs on the wall away from their desks.

But, she added, she understands that phones are a useful communication tool for students who walk home alone from school or who care for a younger sibling in the afternoons.

And as a parent herself, she said, she was empathetic to anxiety about not being able to reach a child in case of an emergency or a worst-case scenario, like a school shooting.

Frierson’s daughter, Eliana, 17, had stronger feelings. She said that it was an overreaction to ban smartphones for the entire day, noting that she often completed school assignments by using her phone.

“It’s an integral part of education,” Eliana said. “It’s wrong to take it away when it’s a tool that is really helpful.”

Smartphones are often part of instruction, particularly in high school. They quickly provide access to Google Translate in foreign language classes or an online graphing calculator in calculus. Many teenagers compose essays and other assignments on phones.

Some students point out that adults seem to rely on their cellphones just as heavily as teenagers do. Ana Sofía Tiberia-Lozano, 16, said she would prefer a policy to be consistent between students and teachers. “Older generations always do think that the new generation is more troublesome,” she said.

Eric Schildge, an eighth grade English teacher in Newburyport, Massachusetts, said he often directs children to take out their cellphones and text a parent when a permission slip or an assignment is missing.

“This feels really myopic, as far as a governor mandating something like this,” Schildge said. “That doesn’t feel like the most workable way for me as an educator to do my job.”

He acknowledged that technology could cause problems in schools but said that the issue went far beyond cellphones. In one of his classes, students compulsively played Slope, a browser-based video game, on their school-issued Chromebooks. He often directed them to close their computers. But over time, he has found that engaging, hands-on lessons are the best antidote to screen time, he said.

This year, his students crafted physical, bound book reports with decorative covers after reading either “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee or “The Nickel Boys” by Colson Whitehead.

“They really appreciated having something they could make and do with their hands.”

Newsom’s announcement is part of a wave of public concern over cellphone and social media use among adolescents. The surgeon general, Dr. Vivek Murthy, has said that social media platforms should carry warning labels akin to those on cigarette packs. In his bestselling book, “The Anxious Generation,” social psychologist Jonathan Haidt argues that parents should delay giving their children access to smartphones and that schools should strictly limit use of them.

Sabine Polak, a parent in Pennsylvania and founder of the Phone-Free Schools Movement, wrote in an email that Newsom’s statement was “great news” but said that she was looking for more detail.

Cellphones should be banned everywhere on campus during the school day, she said, and students who break the rules should have their devices immediately confiscated.

She added that because teenagers will often sneakily use phones hidden in backpacks, the devices should be physically locked away.

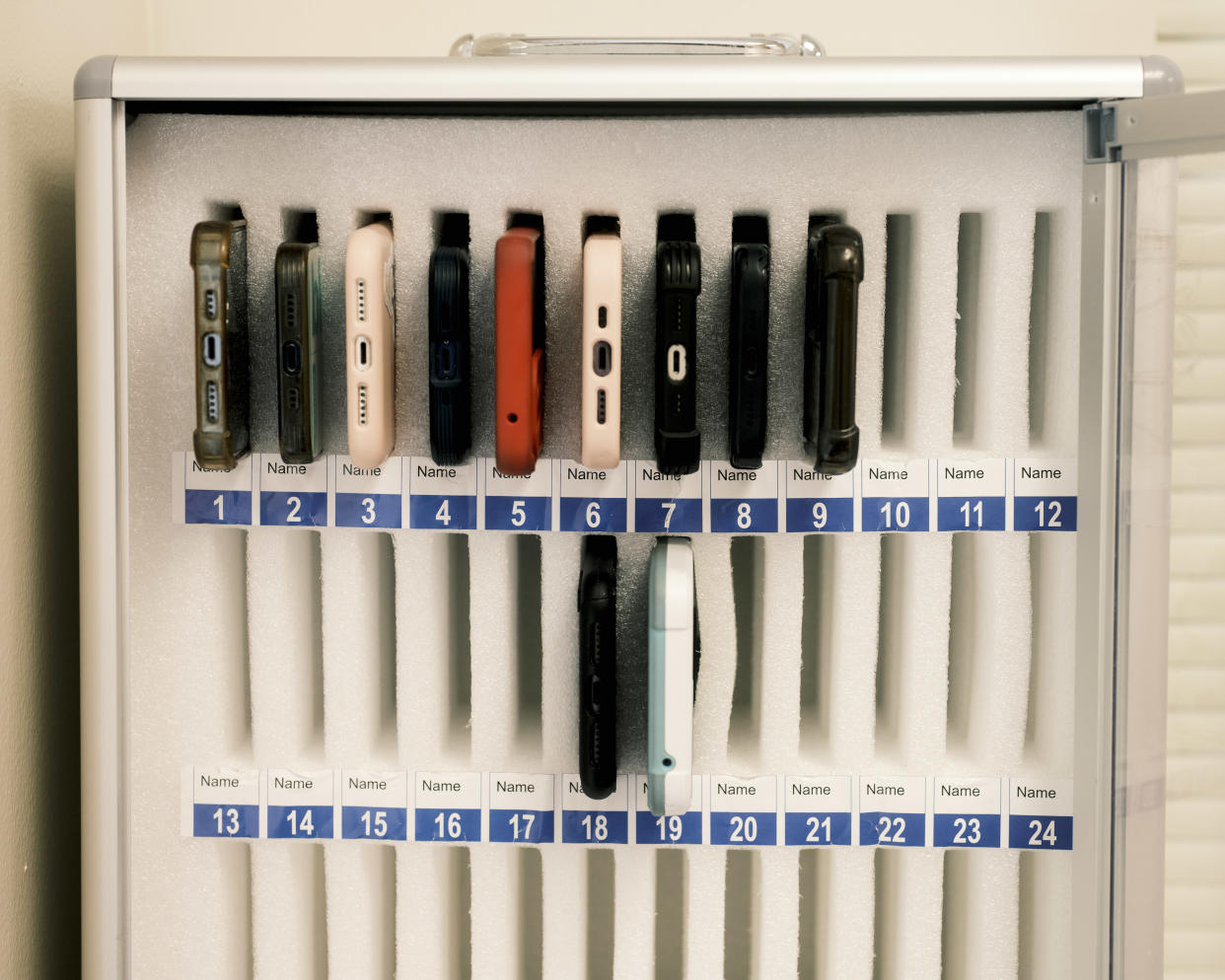

Some schools use a phone pouch called the Yondr, which is locked or unlocked by school staff but can be carried by students throughout the day.

Such devices are rented annually. At Bethlehem High School in Delmar, New York, outside Albany, the district spent $26,773 on 1,400 pouches this past school year.

The superintendent, Jody Monroe, said she was thrilled with the results, noting that teachers no longer had to spend classroom time negotiating with students over phone use and that the overall social climate in the building had improved.

“When phones were allowed, there was an eerie silence that I’m not sure we even noticed at the time,” she wrote in an email. “That is gone now.”

A few dozen parents who initially complained about the policy have quieted down, she added, and some even admitted that they had been wrong.

Patrick Franklin, a high school history teacher in Longview, Texas, in the eastern part of the state, tried to have his own personal ban, requiring students to store phones in another part of his classroom. But he stopped because of the separation anxiety that it had sparked.

“I wish I lived in a world where they aren’t there,” he said, speaking of the phones. “But that’s not the reality I have to deal with. I can’t wish a world where cellphones haven’t permeated every part of society.”

Liz Shulman, a high school English teacher in Evanston, Illinois, outside Chicago, said she had noticed over the past several months more parents acknowledging that teenagers should spend classroom time without phones.

But because some parents still want constant communication, Shulman said she welcomed action from lawmakers like Newsom.

“It’s going to force everybody — administrators, teachers and parents — to focus,” she said.

But there could be pushback. In Capitola, California, Diana Coatney had already planned to get her twins, Zoe and Luke, phones for their 12th birthday in August. But then a bomb threat was called into their middle school.

“Boy, that sure did advance the timeline,” Coatney said, adding that the phone is “a security blanket for me in some ways as much as it is a little bit of autonomy for them.”

c.2024 The New York Times Company