From sheep camp to the city to study uranium’s damage to Navajo people

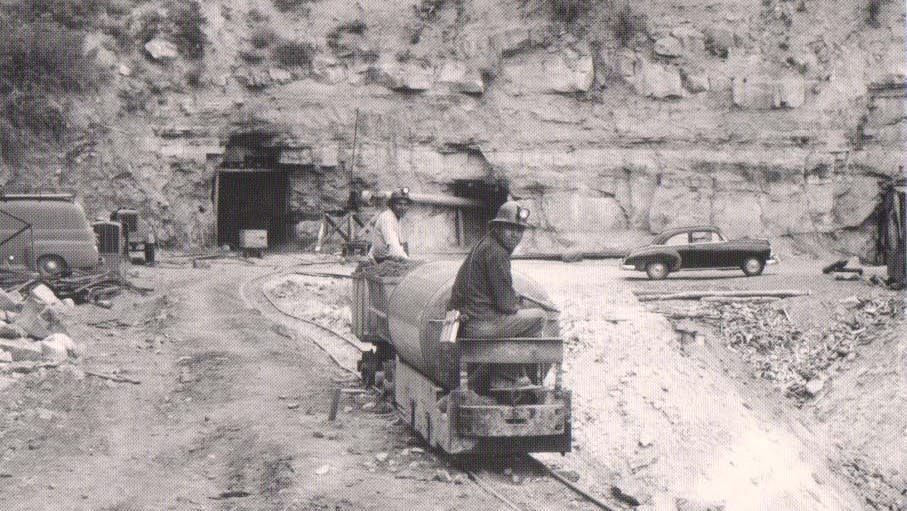

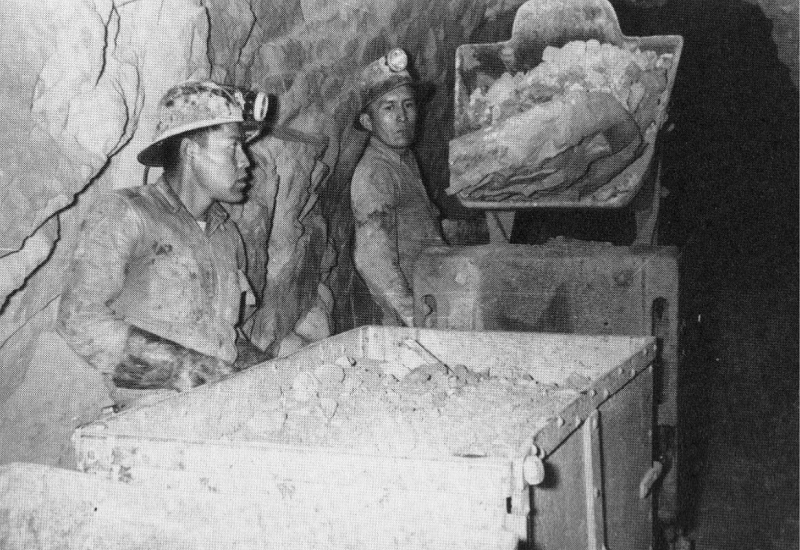

Navajo miners near Cove, Arizona in 1952. Photograph by Milton Jack Snow, courtesy of Doug Brugge/Memories Come To Us In the Rain and the Wind

NEW YORK — Every summer as a kid, Kevin Patterson, 29, hiked up the Lukachukai-Ch’ooshgai Mountains, following the hooves of the sheep and goats to his family’s camp. Up the steep sandstone slope, the young shepherd would stop to rest at the local spring, a paradise in the summer heat. This spring is one of the rare spots on this side of the range where reeds abundantly grow. Locals harvest the reeds for basket making, including the Diné basket commonly used in ceremonies for healing. In 90-degree heat, the spring is a refuge of mist and a place to quench your thirst.

Today, Patterson sits at his cubicle at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, combing through data to understand one of the biggest threats to his community back home. As beautiful as his homelands are, they are contaminated by uranium and vanadium. Between the 1940s and 1980s, uranium and vanadium companies extracted these heavy metals from the Navajo Nation to make nuclear weapons. In doing so, they initiated geochemical processes that mobilized uranium and vanadium into groundwater sources.

In March, this region, now known as the Lukachukai Mountains Mining District, was designated a Superfund site by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. This means that the mining district is listed for priority clean up by the federal government as a Superfund site.

SUBSCRIBE: GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX

Although mining has stopped, the threat is still there. There are more than 500 abandoned uranium mines in the Navajo Nation that need to be cleaned up. Some date all the way back to experiments with nuclear chain reactions at Columbia University that helped start the Manhattan Project. According to the EPA, nearly 30 million tons of uranium ore have been extracted across the Navajo Nation, with families living close by many of these mines, mills and waste sites.

In 2005, the Navajo Nation banned the transport of any nuclear waste going through its lands, an area the size of West Virginia. However, Interstate 40, a major cross-country interstate, crosses the southern section of the Navajo Nation; thus, allowing exceptions to this ban on major highways like Arizona’s State Highways 89 and 160. The ban also prohibits any future mining or milling until all abandoned sites have been cleaned up. Earlier this spring, the Navajo Nation Council and Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren reaffirmed the ban by signing into law its position to call on the Biden administration to halt uranium hauling across Navajo lands.

There is only one place in the U.S. where nuclear waste is processed: the White Mesa Uranium Mill in White Mesa, Utah. The mill, operated by Energy Fuels, Inc., receives waste shipments from as far away as the country of Estonia. The White Mesa Mill is only about 20 miles from the Navajo Nation, just across the San Juan River. According to the Grand Canyon Trust, more than 700 million pounds of toxic waste sits at the mill site. Piles of uranium dust blow in all directions.

Near the Grand Canyon, tribes formed a coalition to prevent uranium mining from occurring at the Pinyon Plain Mine. Last summer, the Biden administration listened to the tribes of the region by designating 1 million acres near Grand Canyon National Park as the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument. The national monument is the fifth national monument designated by the Biden administration through an executive order proclamation.

The same united front has occurred at Bears Ears National Monument in San Juan County, Utah., to prevent the threats of uranium mining in the region from occurring. In 2016, the Obama administration issued this proclamation. The Trump administration reduced its size, but it was later restored by the Biden administration. The designation of these ancestral lands as national monuments protects Indigenous connections to these lands, but also for the beneficial use for all.

Patterson studied Native American Studies and Global Health at Dartmouth College and earned a master’s degree in public health at Columbia, where he is now working toward a doctoral degree in environmental health sciences. His research ranges from the distribution of metal exposures in drinking water and diet across Indigenous communities and their relationships with chronic health conditions.

At his cubicle, he combs through data to get a better understanding of how the legacy of uranium and other metals impacts the entire Navajo Nation and other tribal lands. So far, he has learned that the Indigenous communities he works with are exposed to uranium, measured by uranium levels in their urine, at levels higher than the general U.S. population and subsequently puts them at an increased risk of cardio-metabolic disease and kidney dysfunction.

A study in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine in 2000 found that Navajo men who worked in uranium mines had excessive risk of lung cancer. The Navajo Birth Cohort Study, which is tracking pregnancy and birth outcomes among mothers and babies living near abandoned uranium mines, is another ongoing study. Researchers at the University of New Mexico and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry are working to establish connections between uranium exposure and birth defects.

Patterson is calm, cool and collected. He is very careful with his words. He is tall and handsome, wearing preppy clothes in solid colors — an Indigenous, Ivy-Leaguer vibe. There is no confusion about his purpose: He is here to give back to his community, no matter how deep the opportunity cost is. If he were not here sitting in a cubicle in Uptown Manhattan staring at a computer screen, he could be back at home helping his family. Or doing environmental health research near the Rocky Mountains.

“I grew up not so far from the Colorado border,” Patterson says. “Being in the Rocky Mountains has really influenced the way I see my environment.”

He said he thinks of his studies as an environmental justice issue because some uranium mine workers, like his grandfather, who were underpaid if they were paid at all, suffered serious health consequences. The health problems of mine workers also became a health burden for families like the Pattersons. His own mother developed breast cancer, which the family attributes to uranium exposure. Some of his grandfather’s brothers, cousins, and others of his generation worked in the mining district, too. They not only exposed themselves, but they also exposed their families to the radioactivity from the mines when they came home from work in dirty clothes. When Patterson was growing up and realized that his family was not the only one exposed to uranium’s toxicity, he saw that the contaminant harms whole populations. He wanted to understand this as a problem in public health.

Patterson works as a Superfund research trainee with the Health and Metals lab group at Mailman, which explores the negative health effects from exposure to heavy metals. He also works with Dr. Anne Nigra’s EPI Water Group, which looks at reducing racial and socioeconomic inequities to environmental exposures in public regulated water systems.

He is in the process of preparing for his doctoral qualifying exams and was recently awarded a precision medicine fellowship training grant to help fund his dissertation. So far, Patterson has been published as a co-author in two publications, the Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology in August 2023, and in Nature Communications in December 2022. He also penned a September 2023 editorial for Environmental Health News about his work as Agents of Change for Environmental Justice, advocating for the protection of Indigenous children through clean water access.

In the Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology, Patterson was part of a team that studied how drinking water from unregulated wells and regulated community water systems is a significant contributor to study participants’ internal dose levels of urinary arsenic and uranium, even at low levels of exposure. The study relied on data from the Strong Heart Family Study, which is one of the largest longitudinal epidemiological studies among Native populations, and the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, which studies racial/ethnic diverse urban communities across the U.S. The other study from December 2022 in Nature Communications showed that there are no safe levels of exposure to arsenic or uranium, particularly in Hispanic/Latino and Native American/Alaska Native communities who seem to have high concentrations of both arsenic and uranium concentrations in their regulated water sources.

“I hope that my work helps inform and highlights the repercussions” of the legacy of the uranium mining and milling, Patterson said, adding that the goal of his doctoral studies and research is to help the Diné public learn how they’re exposed to heavy metals and the steps needed to prevent more such exposures from occurring.

The U.S. EPA designates Superfund sites through a national listing that prioritizes federal dollars to help with long-term clean-up efforts to contaminated, polluted sites. The Navajo Nation EPA, which also receives federal dollars, has a Superfund program that enforces the federal laws for cleanup. Near New York City, there are four Superfund sites: Meeker Ave, Newtown Creek, and Wolff-Alport Chemical Company in Queens, N.Y., and Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn N.Y.

Patterson studies this data to find regional patterns. Meanwhile, he wonders just how badly his own family has been exposed, especially now that the whole area has been designated a Superfund Site. This area includes Cove, Lukachukai and Round Rock, Arizona; his families are from both Lukachukai and Round Rock.

The Lukachukai-Ch’ooshgai Mountains are some of the highest peaks across the Navajo Nation, with Roof Butte being the tallest and on the horizon from Patterson’s family sheep camp at 9,823 feet.

“I do think that there has also been a pretty personal interest of my own with the work that I’ve been doing since childhood,” Patterson said.

He said he has a hard time digesting whether to be OK with his community being designated a Superfund site. In some ways, the designation does not change anything at all, except to declare his homelands a priority for clean up by the federal government. Actionable change starts with the community, and he said he hopes that future Diné scientists will continue this work. But his community will forever be impacted, regardless of clean-up efforts. Whether the spring the sheep and goats drank from has traces of uranium and vanadium remains to be studied.

“I honestly don’t know what I would be doing instead. For this lack of knowing otherwise, I feel justified in knowing that I’m doing work that I’m called to,” Patterson said. “I’ve always wanted to pursue a PhD, but the path there wasn’t always clear. Even now, the path forward after the PhD is still unclear, but I want to make a difference for my family and community.”

DONATE: SUPPORT NEWS YOU TRUST

The post From sheep camp to the city to study uranium’s damage to Navajo people appeared first on Arizona Mirror.