Southern Nevada health officials are tracking major increase in mosquito activity

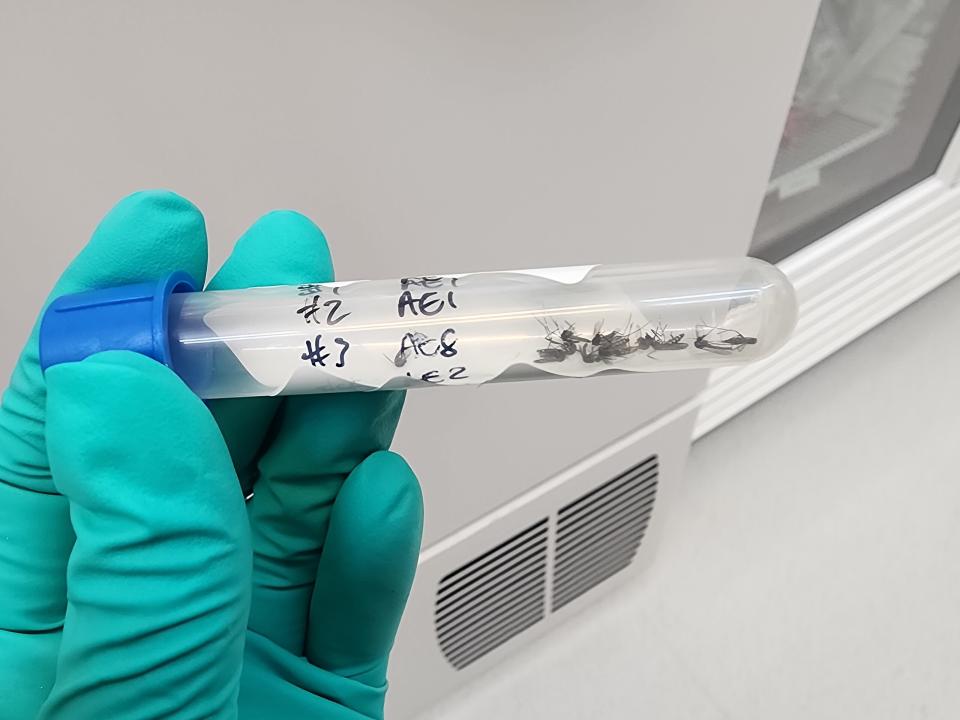

Vivek Raman, the environmental health supervisor for the Southern Nevada Health Department checks mosquito traps. (Photo courtesy of Southern Nevada Health District)

Policy, politics and progressive commentary

Unlike her stealthy common cousin, the female yellow fever mosquito prefers to feed on humans and doesn’t wait for nightfall to take a bite.

Aedes aegypti, an aggressive urban mosquito commonly known as the yellow fever mosquito, was first identified in four North Las Vegas zip codes in 2017. By 2022, the yellow fever mosquito was found reproducing in eight more zip codes in Southern Nevada.

Without any coordinated control or intervention to stop their spread, the urban mosquito made its way to 43, or one-third, of all zip codes in Clark County.

“It was a very rapid expansion of this aggressive urban mosquito,” said Vivek Raman, the environmental health supervisor for the Southern Nevada Health Department.

This month, the SNHD reported the highest level of mosquito activity in the agency’s 20-year history of monitoring. That’s largely due to the explosion of the Aedes aegypti.

Along with the spread came the dramatic increase of public mosquito complaints, from 99 in 2022 to more than 700 in 2023, according to the SNHD.

Health officials expect even more this year. That’s because the mosquitos are arriving earlier than usual. The health department has already received more than 300 mosquito complaints, a significant increase from the 60 received at the same point last year.

It’s not entirely clear why Southern Nevada is seeing an early explosion in its mosquito population, but there are clues.

It’s likely flood conditions in recent years have helped the mosquito population grow. In June 2023, the approximately 90 traps set by the SNHD caught more than 7,000 mosquitoes for testing. So far this June, the health district has already caught more than 26,000, about 19,000 more than last year.

But even when there are drought conditions, the yellow fever mosquito — which requires standing water to reproduce — can thrive. That’s thanks to the yellow fever mosquitoes’ specialized breeding habits.

“Typically mosquitoes prefer to feed on birds, but because Aedes aegypti prefers to feed on people, it has developed habits where it breeds very efficiently and effectively in our yards,” Raman said.

Female yellow fever mosquitoes need much less water to successfully breed compared to the common mosquito. The Aedes aegypti can lay eggs in the amount of water it takes to fill a bottle cap. For the Aedes aegypti, a spare tire, plastic toy, discarded food container, or a saucer under a flower pot is a potential site to lay the next generation of mosquitoes. Their eggs can also lay dormant in dry conditions for as long as nine months.

“Unlike other mosquito eggs that we typically find here, they can remain dry and dormant inside of those little containers until the next rain comes through, or water fills those containers, and then they rehydrate and hatch,” Raman said.

Potential for viruses

Yellow fever mosquitoes aren’t just aggressive biters, they’re capable of transmitting a number of pathogens, including the dengue and zika viruses.

Locally transmitted dengue and zika fever infections — meaning the infected person didn’t get sick abroad — are still rare in the continental U.S. While dengue and zika are infectious diseases, they don’t spread from person to person, only through a vector organism like a mosquito. A mosquito would have to first bite an infected human before being able to transmit the virus to another human.

Still, several states in the U.S. have reported cases of locally transmitted dengue fever infections in recent years, including neighboring Arizona and California. Last October, California health officials reported the state’s first case of locally transmitted dengue in Pasadena.

Those first cases of local transmission may be a warning of what’s to come, said Louisa Messenger, an entomologist and assistant professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas who studies mosquitoes and vector-borne diseases.

The larger concern in Nevada is disease spread by the common mosquito, which can carry the West Nile and St. Louis encephalitis.

In Southern Nevada, two human cases of locally transmitted West Nile virus, another vector-borne virus, were reported in 2023. As of June 17, the SNHD has identified mosquitoes positive for West Nile virus in 25 zip codes. Mosquitoes in another two zip codes tested positive for the virus that causes St. Louis encephalitis.

The most mild symptoms of West Nile and St. Louis encephalitis are similar to the common flu: fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, and fatigue. But in the most severe cases those infected with the viruses can develop a neuroinvasive form of the disease that can cause paralysis or a coma.

“This year is unprecedented,” Messenger said. “It’s the largest number of mosquito pools testing positive at the earliest point in the transmission season, which lasts until around October.”

“We are all quite concerned at the moment that so many mosquitoes are potentially positive for this virus out in the environment, and that we may see a ramp up in disease transmission in the following weeks,” she continued.

Climate change

The relationship between climate change and disease is complex. Much is still unknown about how virus-carrying mosquitoes will react to climate change, but research shows a clear connection between heat and mosquitoes, said Messenger.

Rising temperatures allow mosquitoes to grow faster and live longer. Cooler winters help reduce the survival of mosquito larvae, but with warmer temperatures in the spring and fall due to climate change, they have a greater shot at survival and longer breeding seasons to build up their populations.

“Mosquitoes and other insects are really sensitive to small changes in temperature and humidity because their life cycles are so intrinsically linked to temperature,” she continued.

Heavy rains from extreme weather events can also cause water to pool and stagnate, creating conditions for mosquitoes to thrive. Last year, a series of heavy storms — including Hurricane Hilary — flooded the valley and left behind large pools of warm stagnant water perfect for mosquitoes to establish a breeding population.

“When there’s more rain and stagnant water for several days afterwards, and the weather’s nice and hot, that’s the sort of perfect conditions for mosquitoes to breed,” Messenger said.

No mosquito control plan in Nevada

Each breeding season, the SNHD places mosquito traps near potential mosquito hot-spots in order to monitor the presence of West Nile and other viruses, but mosquito prevention is largely out of their hands, Raman said.

Southern Nevada does not have an established mosquito control program to oversee the treatment and elimination of mosquito breeding, despite their growing presence.

Mosquito abatement programs in the U.S. have proven effective at reducing mosquito populations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warns that the only way to reduce mosquitoes and the dangers they pose is a comprehensive hands-on approach, including monitoring, targeted pesticide use, and systemic interventions by local governments.

However, establishing a mosquito control program would likely require dedicated funding and support from local government, said Raman.

“We need sustainable solutions. It’s not just a shot in the arm, you have a program for a year, and then it goes away. This is something that will require sustainable solutions for long-term improvement.”

The post Southern Nevada health officials are tracking major increase in mosquito activity appeared first on Nevada Current.