Storm chasers catch tornado winds above 300 mph in rare 'intercept'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The tornado raced across southern Iowa at nearly 45 mph, shredding wind turbines like string cheese.

In the town of Greenfield, it overturned cars and ripped homes from their foundations, leaving a gash of destruction that can be seen from space. The twister, which the National Weather Service later rated an EF4, killed five people May 21, making it one of the deadliest so far this year, and injured 35.

More than a dozen tornadoes touched down in the state that day. While most everyone in the area hunkered in basements, a team of nine scientists — storm chasers — sought to get as close as possible to the twisters.

Just before 3 p.m., they saw their opportunity. As a tornado began to brew on their radar screens, the group scrambled into action. They rushed one of their radar trucks to a location about 10 miles west of Greenfield, a community of about 2,000 in southwest Iowa.

Another team dashed to deploy a pod of scientific instruments directly in the twister’s path.

“There was debris falling on us,” said Jennifer Walton, a storm chaser and photographer on the team.

A third truck drove through town, suddenly surrounded by trees and buildings that blocked their radar view of the twister. They knew they were ahead of the storm; they didn’t know by how much.

“That’s probably the most anxious time for all of us, because we know a tornado is coming,” said Joshua Wurman, a University of Illinois research scientist. “We really don’t know whether it’s coming in five minutes or three minutes or two minutes.”

It worked. The team achieved an “intercept,” as they call it, collecting data on the storm with the pod and two mobile radar devices and giving scientists a rare, detailed and close-range view of one of the most powerful twisters ever recorded this way.

The data they gathered marks only the third time that scientists have calculated wind speeds that reached more than 300 mph within a tornado. And because the storm chasers took the readings from multiple angles while the twister pummeled Greenfield, the findings now offer a grim view of the winds and inner dynamics of a vortex powerful enough to level homes.

“Tornadoes producing this intensity and this kind of damage are rare in the United States. We only get a handful of these each year,” said Tony Lyza, a physical scientist at the National Severe Storms Laboratory in Norman, Oklahoma, who was not involved in the research. “This is a really important study to have a tornado of this intensity and have a mobile radar there observing while the tornado was doing peak estimated damage.”

Many basic elements of tornado science remain unsettled because high-quality data is so hard to obtain. These new findings could help untangle critical questions about tornado formation and structure, how wind speeds in the air correspond to damage on the ground and the factors that can cause tornadoes to intensify or break down.

The team of nine researchers that set off for Greenfield on May 21 was led by Wurman and Karen Kosiba with the University of Illinois Flexible Array of Radars and Mesonets (FARM) team, which is funded in part by the National Science Foundation. The two are among the world’s top academic storm chasers.

The FARM researchers started the day in McCook, Nebraska, weary after a night of storm-chasing in Colorado, where all they’d caught were hailstones. The roving team travels with two radar trucks and several other vehicles, including a pickup truck with a pod of instruments designed to survive a tornado long enough to measure temperature, pressure and other factors. They set off for Greenfield — a nearly six-hour drive.

Chasing a tornado is like playing a board game against nature. Researchers evaluate the conditions, calculate odds and move pieces — radar trucks, balloons and pods — so that they can capture the best measurement of the storm from a relatively safe distance.

This kind of work can be deadly — in 2013, three tornado chasers died while pursuing a powerful tornado in El Reno, Oklahoma.

In Iowa, the FARM researchers’ day began like a game of whack-a-mole. Storms were moving through the area rapidly, which left them guessing as to where to position their equipment and how to keep a safe distance. They found themselves zigzagging down country roads as storms popped up on radar, only to watch them fizzle out.

But as the Greenfield tornado approached the town, it touched off 10 minutes of intense action.

“This isn’t a safe sport. You have to be able to make change on a dime,” Walton said.

Kosiba and Wurman stationed their radar truck about a mile east of the town’s center, which was about 300 yards from the twister’s edge. They lowered the truck’s metal hydraulic feet and lifted its wheels to create a stable, level platform to ride out the storm.

“We don’t want to be bouncing around and messing up our radar,” Wurman said.

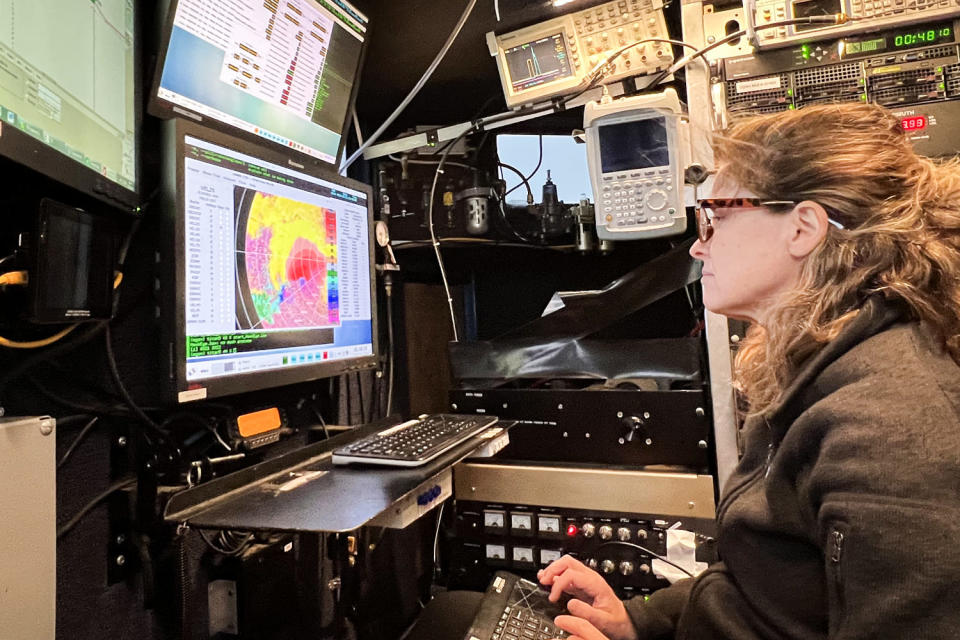

Winds ripped by the truck at about 80 mph, but the researchers don’t remember much of how it looked outside — they were glued to their screens.

“I never look out the window,” Kosiba said. “I’m always looking at the radar.”

The truck sends out a narrow beam of radar waves that hit objects flying through the air, everything from raindrops to two-by-fours. The device measures the energy that returns, providing data so detailed that researchers can understand the shape of raindrops falling.

Inside the truck, they watched colors flash across displays as the tornado splintered house frames and ripped apart trees.

At times, multiple vortices swirled within the tornado, which lasted for about 45 minutes and traveled about 44 miles. For less than a second, the researchers calculated wind speeds of more than 300 mph in a portion of the tornado.

“This was a violent day in Iowa,” said Tim Marshall, a veteran storm chaser based in Texas who was not involved in the research.

The weather service said the twister was up to 1,000 feet wide at times. But when it hit Greenfield, it had narrowed. Scientists aren’t quite sure why that happened — it’s one of many mysteries this kind of detailed radar data could eventually help solve.

“We’ll be chewing on this for years,” Wurman said.

The ingredients necessary to form a tornado — wind shear, lift, instability and moisture — are well known and allow forecasters to put out reliable tornado watches but, beyond that, much remains mysterious.

“Once a storm forms and makes a tornado, we have very little skill in knowing whether that tornado is going to be large or small, long-lived or short-lived, or the exact track that that storm is going to take,” Wurman said.

Storm chasers execute their dangerous dance with the elements to push their field forward.

The recent measurements of the Greenfield tornado, in particular, could offer insight into how wind speeds aloft translate to damage on the ground. Kosiba plans to correlate the detailed wind speed data her team gathered with surveys of ground damage. She also plans to model the event’s thermodynamics, which could offer clues to what factors can lead to more intense wind speeds.

This work could help scientists develop better tornado prediction systems and help builders construct more resilient structures.

“We don’t want to see the destruction, but this is how we learn,” Marshall said. “The damage is Mother Nature’s fingerprint. It’s how we evaluate how it happened.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com