The Best Social Media Site Still Looks Like It Was Made in the 1990s

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

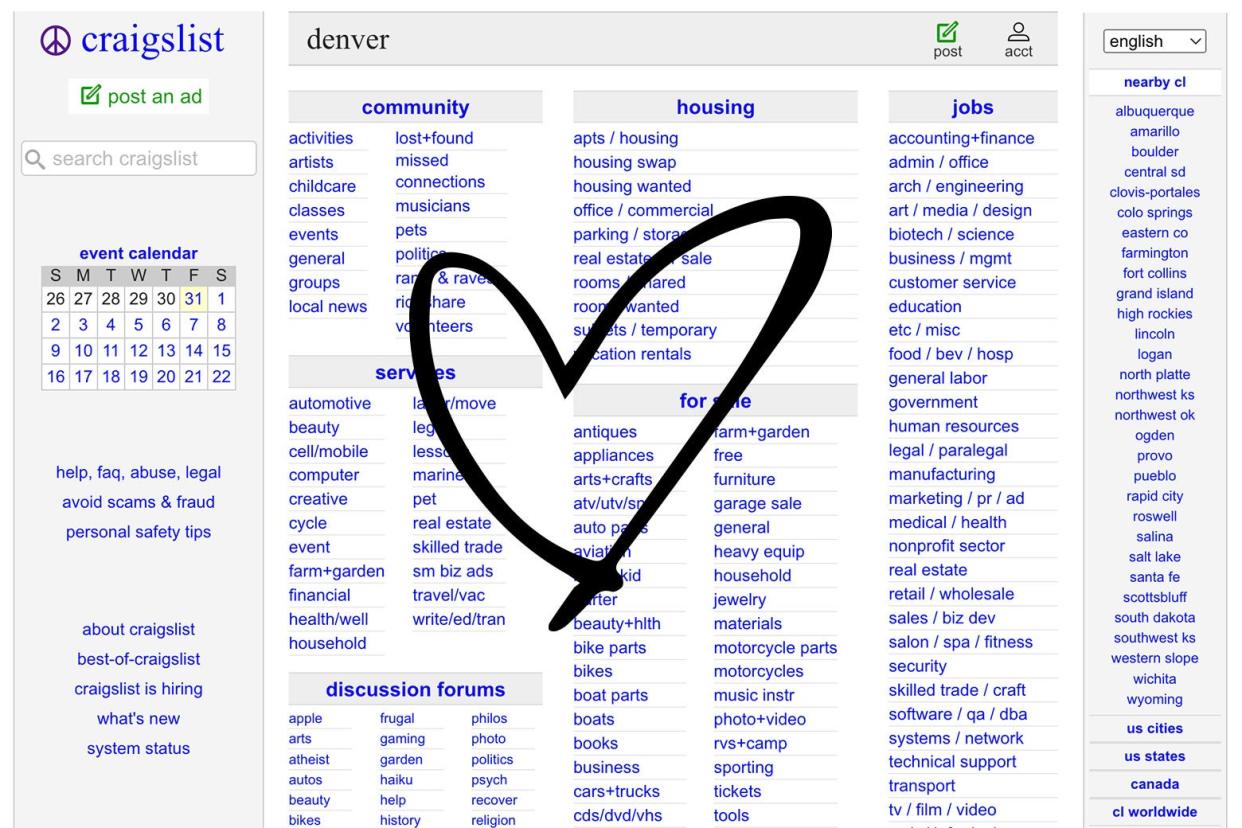

In August 2009, Wired magazine ran a cover story on Craigslist founder Craig Newmark titled “Why Craigslist Is Such a Mess.” The opening paragraphs excoriate almost every aspect of the online classifieds platform as “underdeveloped,” a “wasteland of hyperlinks,” and demands that we, the public, ought to have higher standards. The same sentiment can found across tech forums and trade publications, a missed opportunity that the average self-professed LinkedIn expert on #UX #UI #design will have you believe that they are the first to point out. But as sites like Craigslist increasingly turn into digital artifacts, more people, myself included, are starting to see the beauty that belies those same features. Without them, where else on the internet could you find such ardent professions of desire or loneliness, or the random detritus of a life so steeply discounted?

The site has changed relatively little in both functionality and appearance since Newmark launched it in 1995 as a friends and family listserv for jobs and other opportunities. Yet in spite of that, it remains a household name whose niche in the contemporary digital landscape has yet to be usurped, with an estimated 180 million visits in May 2024. Though, it’s certainly not for a lack of newcomers attempting to stake their claims on the booming C2C market; in the U.S., Facebook Marketplace, launched in 2016, is its closest direct competitor, followed by platforms like Nextdoor and OfferUp.

Craigslist’s business model is quite simple: Users in a few categories—apartments in select cities, jobs, vehicles for sale—pay a small but reasonable fee to make posts. Everything else is free. Its Perl-backed tech is straightforward. The team is relatively lean, as the company considers functions like sales and marketing superfluous. This strategy has allowed Craigslist to stay extremely profitable throughout the years without implementing sophisticated recommendation algorithms or inundating the webpage with third-party advertisements. Its runaway success threatens decades-old industry gospels of growth, disruption, and innovation, and might force tech evangelists to admit they don’t fully understand what people want.

The profile continues on to paint Newmark as sort of an asocial, aging hippie, more interested in feeding hummingbirds in his backyard than contemplating monetization. It concludes that Craigslist’s implicit political philosophy has a “deeply conservative, even a tragic cast.” The purple peace-sign logo was just the cherry on top of this big, deliberate farce.

A generous reading of such charges may allude to criticisms leveled at the politics of early technologists, many of whom saw the internet as the natural extension of the failed “New Communalist” project of the 1970s (and then later went to bed with actual conservatives as part of their techno proselytism). New Communalists pushed a “politics of consciousness” that insisted every human was part of the same whole, a revelation one could attain by doing a lot of acid. Newmark ran in these circles and was a member of early virtual communities like WELL (Whole Earth ’Lectronic Link), which was cited as a direct inspiration for Craigslist.

While some of their more militant leftist counterparts took to the streets to protest Vietnam and civil rights injustices, the New Communalists engaged in psychological and political retreat, a kind of collective agoraphobia. They left the cities and suburbs for the countryside, where violence could be relegated to distant memory. Here, failed bureaucracies could be replaced with hyperlocal governance. In such utopian visions, hierarchies would cease to exist, fundamental trust and mutual goodwill would serve as social security, and advances in small-scale technology would help guide the way.

Their belief that the root of societal ills lay in the failure to connect and understand one another lives on in the “connectionist” philosophy and strain of Californian libertarianism which undergirds many modern tech products and companies. Facebook, for example, genuinely believes that by building the infrastructure to connect people, it can affect meaningful social change.

A noble goal, at least on paper. Former Facebook spokesperson (and sister of CEO Mark) Randi Zuckerberg once opined that anonymity on the internet had to be done away with, that people “behave a lot better when they have their real names down,” a sentiment that she was not alone in espousing. The premium on openness was first extended via calls for user transparency—the creation of profiles that used real names and information for real people. Facebook has since adopted “transparency” as an umbrella term for any efforts taken to improve platform safety, which runs the gamut from reviewing content for spam to the suppression of free speech and political dissent.

(In light of the Cambridge Analytica leak, the company responded to overwhelming public and political pressure by again deploying the rhetoric of transparency, but this time in the form of a renewed commitment to advertiser accountability.)

Such a Hobbesian view of human nature, dressed up in shiny new sheep’s clothing, has effectively produced a stalemate of faith: the world’s largest social media platform has never fully trusted its users; now its users don’t fully trust it.

Craigslist, from the start, chose a different path. And while that has allowed it to eschew many issues plaguing its competitors today, its generally hands-off approach has created a host of different problems. The platform came under fire for enabling sex trafficking and a few sensationalized murder cases in the 2010s. In 2018, Craigslist permanently shuttered its personal ads section following a federal amendment to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, a bedrock piece of legislation that enabled early websites to flourish by removing liability for user-generated content. The move was widely lamented by everyone from longtime posters and lurkers to sex workers and their advocates, the latter of which argued that the platform had provided significant protections to an otherwise highly vulnerable population. For most, the biggest concern to date is the site’s minefield of scams that prey on ignorance, naïveté, and digital and financial illiteracy.

When venturing out in the world, a degree of caution is justifiably warranted. But fear of the unknown is a powerful emotion, and one that often gets invoked regardless of whether those fears are rooted in reality. In a 2017 Wired profile, Reham Fagiri, the founder of secondhand furniture marketplace AptDeco, in discussing her company’s value proposition references a Craigslist meetup gone wrong and the safety concerns experienced by women during these face-to-face transactions. Verification tools can be helpful or downright necessary, though frequently they still fall short; an image and profile of the person on the other end of an interaction allows for trust to be established. So the fundamental, and increasingly difficult, question that Craigslist faces becomes this: Without this information, how can we continue trusting one another?

The answer in many ways is unbelievably simple, at least for Craigslist’s millions of users: You just do. You risk trusting whoever is on the other end, at least in the beginning. Is that not the same negotiation all relationships require of us at one point? Notably, Craigslist is not a perfect model for the world; at the end of the day it’s still a for-profit company. But these aspects certainly speak to broader, thornier questions for those of us invested in political change: What would it look like to care about others, no matter how different they are from us? When the world starts feeling bleak, how do we avoid retreat and rather move forward together?

So as purportedly “social” networks morph into virtual malls—only with less clearly defined storefronts—or mere echo chambers of our existing interests, the platform whose stated purpose is to facilitate buying and selling has started to feel the most social of all. These days I find myself casually browsing Craigslist in lieu of Instagram. Like readers of a local paper, I use it to keep a pulse on what’s happening around me, even if I’ll never know who these people are. That’s beside the point.

Perhaps Craigslist’s single greatest cultural contribution, and my favorite place to lurk, is the “missed connections.” The feature has inspired countless copycats, artistic reinterpretations, human interest stories, and analyses (one in particular extrapolated that Monday evenings are the most lovelorn time across the country). There is something deeply comforting about seeing those intangible threads of yearning which permeate a city so plainly laid out, as confirmation that you’re not alone in wanting to be seen by others alive in the same place and time as you.

Sometimes I’ll peruse random job listings or the “free” section. This leads to the ever-amusing exercise, which I’ll often invite friends to participate in, of speculating about the motivations and circumstances behind an object’s acquisition and imminent relinquishment. I’ll even visit the clunky, dial-up era–style discussion forums, subdivided into topics labeled things like “death and dying” or “haiku hotel,” where a unique penchant for whimsy and romance can be felt deeply throughout. On Craigslist, a post can be a shout into the void that may or may not be returned, an affirmation of life, but regardless, in 45 days it’s gone. Positioned somewhere in between digital ephemera and archive, the site’s images and language are often utilitarian, occasionally unintelligible, and just when you least expect it, absurd, poetic, and profound.

Frequently, technologists remain convinced that the market will eventually reveal a solution for all of our deep-seated societal problems, something that we can hack if only granted access to better tech. From the start, the industry has advanced the idea that change is inherently good, even if only for its own sake, which can be viewed as symptomatic of the accelerating conditions of late-stage capitalism. Of course, there are many ways in which change is desperately needed in this moment, but when it comes to the particular case of Craigslist, it hardly seems necessary.